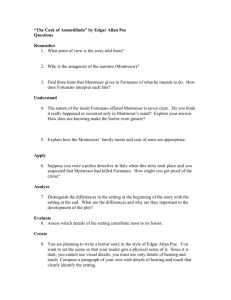

The Cask of Amontillado - Hatboro

advertisement