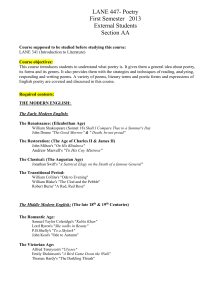

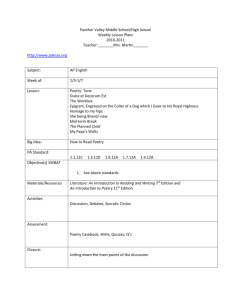

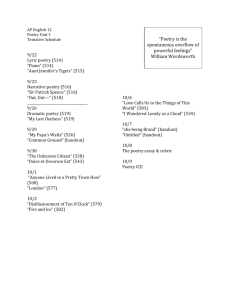

Cranng 13 winter 2006/spring 2007

advertisement