1. four-part harmony / voices

advertisement

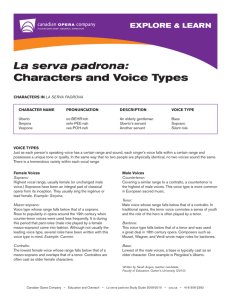

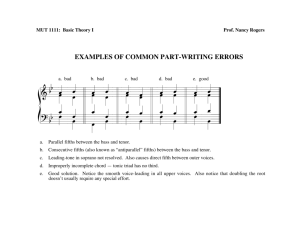

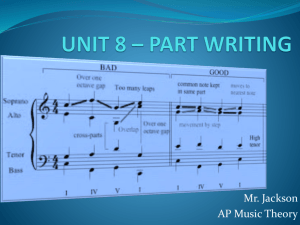

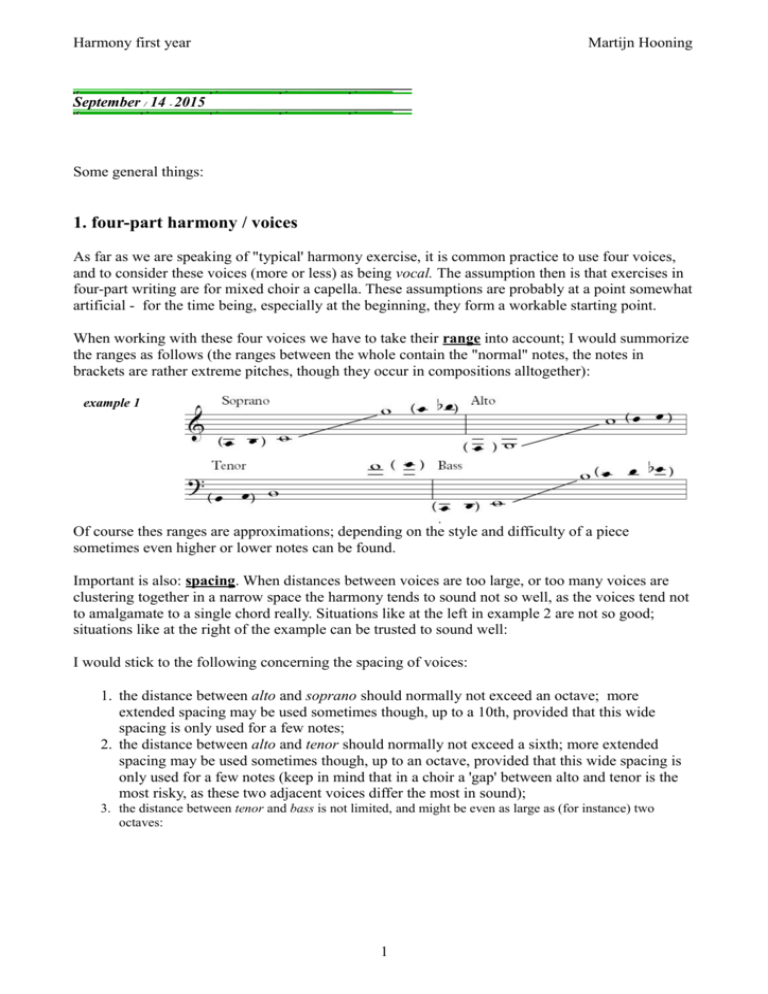

Harmony first year Martijn Hooning September / 14 - 2015 Some general things: 1. four-part harmony / voices As far as we are speaking of "typical' harmony exercise, it is common practice to use four voices, and to consider these voices (more or less) as being vocal. The assumption then is that exercises in four-part writing are for mixed choir a capella. These assumptions are probably at a point somewhat artificial - for the time being, especially at the beginning, they form a workable starting point. When working with these four voices we have to take their range into account; I would summorize the ranges as follows (the ranges between the whole contain the "normal" notes, the notes in brackets are rather extreme pitches, though they occur in compositions alltogether): example 1 Of course thes ranges are approximations; depending on the style and difficulty of a piece sometimes even higher or lower notes can be found. Important is also: spacing. When distances between voices are too large, or too many voices are clustering together in a narrow space the harmony tends to sound not so well, as the voices tend not to amalgamate to a single chord really. Situations like at the left in example 2 are not so good; situations like at the right of the example can be trusted to sound well: I would stick to the following concerning the spacing of voices: 1. the distance between alto and soprano should normally not exceed an octave; more extended spacing may be used sometimes though, up to a 10th, provided that this wide spacing is only used for a few notes; 2. the distance between alto and tenor should normally not exceed a sixth; more extended spacing may be used sometimes though, up to an octave, provided that this wide spacing is only used for a few notes (keep in mind that in a choir a 'gap' between alto and tenor is the most risky, as these two adjacent voices differ the most in sound); 3. the distance between tenor and bass is not limited, and might be even as large as (for instance) two octaves: 1 example 3 Some examples of spacing: Different harmonizations of the same melody. You can listen to the example. As you may have observed when looking at example 3, we speak of closed position (or: wide position) when no tone(s) of the chord could be placed between alto and soprano, nor between alto and tenor; when tones can be placed between alto and tenor and alto and soprano we speak of open position (or: narrow position). When only one tone could be placed in between we eventually could speak of: mixed position. As you can see, the bass plays no role when using these labels: example 4 In instrumental music composers tend to be more free concerning the spacing within chords than in vocal music. Sometimes we even find quite extreme spacings, which certainly are not useable in vocal music, but obviously are o.k. in instrumental music. Interesting examples are for instance in the late work of Beethoven, especially in the Piano Sonatas; extreme distances between two or three (very) high voices and one, two or three low voices are quite common in the last six sonatas - see the example below (from Op. 111): example 5 Beethoven, Piano Sonata Op. 111, beginning of the second movement (youtube) 2 Recording for instance here When playing harmony on the piano (or on another keyboard instrument) we often play three voices in the right hand, and only the bass in the left hand (though it is sometimes necessary or feasable to move the tenor to the left hand). We can label this typus of harmony playing (or writing) as "keyboard style", as opposed to "vocal style" where often the voices are at least somewhat farther apart (and the tenor tnds to be lower). Compare the examples below: example 6 Different harmonizations of the same melody You can listen to the example. Recording of the Bach Choral for instance here (youtube / 1'05'') The notation we normally use when writng harmony is not exactly the most common notation of music for (a capella) choir: Normally four staves are used; soprano and alto are then in violin clef, and the bass is in bass clef; for the tenor we nowadays normally use an octavating violin clef (we have to read the tenor an octave lower). See example 5a. Throughout history though another notation has been common, using C clefs: soprano (or eventually: mezzosoprano) clef, alto clef, tenor clef (or eventually baritone clef) and bass clef. In example 5b you can see what the Bruckner excerpt would look like when using soprano, alto, tenor and bass clefs: example 7 Beginning of a Motet by Bruckner, using modern (left) and C clefs (right) Recording for instance here (youtube) 3 4 The notation on two staves we mostly use when writing harmony has some practical advantages (easier to read / play); a clear disadvantage is the quite illogical use of the bass clef for the tenor this leads very often to quite some, if not too many auxilary lines (and example 3 may serve as a distinct example!). Apart from the fact that four-part homophonic writing has been at some points in history an important musical category, writing harmony in 4 voices (as opposed two, for instance: three, or five) has the practical advantage that we always can use all common chords: triads and seventh chords. And that we can choose doublings (=using one tone of a chord twice when writing a chord), in by that emphasize one of the tones of the chord (see also below). 2. Movement of the voices Very often in harmony stepwise motion prevails - which is not to say that leaps do not occur as well. But especially large leaps can have the effect that the cohesion of the chords is diminishing or even lost alltogether, or can result in unclarity of, or careless writing of the horizontal course of a voice. Moreover, we have to keep in mind that leaps nearly always are more difficult to perform and to perceive than steps. And that descending leaps are often more complex even than ascending leaps, and dissonant leaps more complez than consonant ones. Therefore I would like to 'prescribe' the following: 1. leaps larger than a descending major sixth or an ascending minor seventh are better avoided; leaps of an octave nevertheless are useable, in both directions. 2. augmented intervals in a voice are (much) less good than diminished intervals; when you have the choice, and have written an augmented interval, be advised to invert it to a diminished one. Even a larger interval like a diminished seventh is in most cases a better idea than an augmented second (but, see example 10!). 3. try to avoid successive leaps in the same direction, unless these leaps together form an arpeggiated chord; and you can stretch this premise a little: leaps like, say, D - G - C (fourths up) are often o.k. as long as the last note forms a suspension to a tone in a chord to which the other notes belong as well (example, in this case: the C may act as suspension to B, in a G chord). 4. It is often a good idea to 'compensate' leaps in a melody by writing a step or a leap in the opposite direction after and/or before the leap(s), in this way wholly or partially "filling the gap" caused by the leap. 5. Leaps are harder to sing in a fast than in a slow tempo - and for that obvious reason they occur less often in faster tempi or small note values. example 8 Leaps You can listen the example. to We can of course describe exactly how the individual voices move with respect to each other - for example, that one voice stays on the same tone while another ascends, or that wo voices move in the same direction etc. We can use these terms: 5 • Similar motion: Two or more voices move in the same direction, but not in exactly the same intervals (Dutch: gelijke beweging) • Parallel motion: Two or more voices move in the same direction, in exactly the same intervals (though we normally continue to speak of parallel motion when the size of the intervals differ as n: one voice moves a major third, and another a minor third up etc.) (Dutch: parallelle beweging) • Oblique motion: Two or more voices move, whereas at least one voice stays on the same note (or repat that note) (Dutch: zijdelingse beweging) • Contrary motion: Two or more voices move in opposite directions (Dutch: tegenbeweging): example 9 Similar, parallel, oblique and contrary motion You can listen the example. to Sometimes we encounter voice crossings in four-part homophonic music. It is wise though to avoid them at the beginning alltogether (as they often lead to mistkaes), but nevertheless here a few remarks: • It is unusual that the outer voices (soprano and bass) are involved in a voice crossing. After all: If the alt rises above the soprano or the tenor is below the bass it may become unclear which notes in fact belong to the melody respectively the bass. • So: Most voice crossings occur between the middle voices (alto and tenor). Often they result from melodic curves in one of these (or both) voices, or they are used as a special means of expression. Below you see some examples from J.S. Bach's Chorals. By the way: The Bruckner motet in example 7 above shows that other voice crossings exist (in this piece very distinctive crossings between alto and soprano). example 10 Fragment of Choral 170: Very expressive leap in the tenor (octave up) resulting in a short crossing with the alto. Fragment of Choral "Es ist genug" from Cantata O Ewigkeit du Donnerwort BWV 60; expressive voice crossing between alto and tenor, in measure 1. Apart from that: The example shows that "wrong / augmented" intervals can be very expressive! Recording for instance here (youtube / 14'31'' ) This Choral has been used by Alban Berg, in the Violin Concerto; see this short youtube excerpt from the Concerto 6 Choral "Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden, from Part II of the Mathew Passion. Voice crossing in measure 1 between alto and soprano, probably connected with the ascending motif (two eight notes + quarter note) that appears on the first and third beat. Recording for instance here (youtube) will follow soon: 3. Connection of chords: distances and common tones; parallels 4. Doublings (in root positions and I6, IV6 and V6) 5. Leaps without change of harmony / chord - moving from open to closed position and vice versa 6. Degrees 7. Degrees and functions 8. Figured bass 9. Cadences 10. Schemata 7 8 9