I, Too, Sing America

advertisement

I, Too

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I'll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody'll dare

Say to me,

"Eat in the kitchen,"

Then.

Besides,

They'll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamedI, too, am America.

-Langston Hughes ( 1902-1967)

The Harlem Renaissance

I

n the early 1920s, African American artists, writers,

musicians, and performers were part of a great cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance.

The huge migration to the north after World War I

brought African Americans of all ages and walks

of life to the thriving New York City neighborhood called Harlem. Doctors, singers, students,

musicians, shopkeepers, painters, and writers

congregated, forming a vibrant mecca of cultural

affirmation and inspiration.

As Langston Hughes wrote, "It was the period when

the Negro was in vogue." Marcus Garvey's "Back to

Africa" movement was in full swing. The blues were vibrantly alive; jazz was just beginning. An all-black show,

Shuffle Along, opened on Broadway with the performers Josephine Baker and Florence Mills, music composed by Eubie Blake, and lyrics by Noble Sissie. And

mainstream America was developing a new respect for

African art and culture, thanks in part to its reflection

in the work of the modernist artists Pablo Picasso and

Georges Braque.

Against this backdrop, Harlem Renaissance artists insisted that the African American be accepted as "a collaborator and participant in American civilization," in the

words of the educator and critic Alain Locke. Writers

such as Jean Toomer and Zora Neale Hurston (page 750)

wrote about the African American experience. Artists

such as Aaron Douglas and William H. Johnson painted it.

The photographer James Van Der Zee recorded it with his

camera. The trumpeter Louis Armstrong and the pianist

Fletcher Henderson set it to music, and vocalists Bessie

Smith and Ma Rainey sang it.

Harlem newspapers and journals, such as Crisis and

Opportunity, published the work of both new and established African American writers. To promote and

support intellectually gifted young people, the journals

sponsored literary contests that encouraged creative

writing and rewarded it with cash prizes and social introductions to the top writers of the time.

In autobiographies, poetry, short stories, novels,

and folklore , African American writers afBessie Smith.

firmed the role of black talent in American

Brown Brothers.

culture and focused on different aspects of

black life in Harlem, the South, Europe, the

-l

:r

!II

""tJ

§

0 -a·

....,.,

~~

I»

iD

~· a

.... 0

~~

;:r.,

....

I»

:r

-n ::;·

!II

;;J~

::J 0

n ::J

::;· ·

0

!II

[0

!II

)>

., n

"'.&I

C)!:.

I» .,

=!II

!II c..

~• -o

Vl~

!II

I»

:::;

IV

.

()

iDO

~~

)>~

.

'<

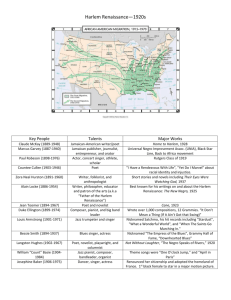

The Migration of the Negro, Panel No. I ( 1940-1941) by Jacob Lawrence.

Tempera on masonite ( 12" x 18 ").

Caribbean, and even Russia. They addressed issues of race, class, religion, and gender. Some writers focused entirely on black characters,

while others addressed relationships among people of different races.

Some writers attacked racism; others addressed issues within black communities. A by-product of African American writing was the affirmation

that black dialects were as legitimate as standard English.

Unfortunately, by the early 1930s, the Great Depression had depleted

many of the funds that had provided fmancial support to

individual African American writers, institutions,

and publications. Nevertheless, Harlem and

African American culture were forever

changed. The foundation was laid for

Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin,

Gwendolyn Brooks, Alice Walker,

Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou,

Terry McMillan, Rita Dove,

and thousands of other

African American writers,

painters, composers, and

singers to make their feelings and experiences

part of American artistic

expression: "1, too, sing

America."

Louis Armstrong.

Brown Brothers.

z

~

cr

:I

eL

CP

5

;::r

Cl

eL

~

~

~

:I"

i"

?

0

0

()

0

r:::

~

'<

)>

~

;XI

Ill

0r:::

rl

.J1l

z

:-<

James Weldon Johnson (c. 1925) by Winold Reiss.

Pastel on artist board (30 lf16" x 21 9/16").

ten years. In 1931, he was appointed professor

of creative literature at Fisk University. Seven

years later, he died in an automobile accident.

Although some of Johnson's early poems are

in dialect, he soon abandoned that style for

standard English, which he felt was capable of

greater variety and power. His principal theme

was black pride, which he celebrated in such

poems as "Fifty Years," written on the fiftieth

anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation,

and "0 Black and Unknown Bards," a tribute to

the anonymous authors of African American

spirituals. With his brother, the composer John

Rosamond Johnson, he wrote a number of very

successful light operas and songs for Tin Pan

Alley, and the brothers collaborated in editing

two collections of spirituals.

Johnson was an important leader of the first

phase of the Harlem Renaissance. His anthology,

The Book of American Negro Poetry ( 1922), was one

of the significant early collections of poems by

African Americans. In addition to poetry, Johnson

wrote fiction (most notably The Autobiography of

an Ex-Colored Man, published in 1912), nonfiction

studies of black life, and an autobiography, Along

This Way (1933).

James Weldon Johnson

(1871-1938)

ames Weldon Johnson-poet, teacher, and

lawyer-was born in Jacksonville, Florida.

Educated at Atlanta University in Georgia and

Columbia University in New York City, he

was the first African American to be admitted

to the Florida bar after Reconstruction.

Throughout his career, Johnson was an energetic exponent of civil rights, and in his writing

he constantly sought recognition for the contributions that African Americans had made to

American culture.

After serving as U.S. consul in Venezuela and

then in Nicaragua ( 1907-1913), Johnson

worked as field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) for four years and then served as the

association's general secretary for the following

J

It was Johnson's extensive research for one

collection, The Book of American Negro Spirituals

( 1925), that inspired his poem "Go Down,

Death." Describing this experience, he said:

"The research which I did in collecting the spirituals and gathering the data for my introductory

essay had an effect on me similar to what I received from hearing the Negro evangelist

preach .... I was in touch with the deepest revelation of the Negro's soul that has yet been

made, and I felt myself attuned to it. I made an

outline of the second poem that I wrote of this

series. It was to be a 'funeral sermon: I decided

to call it 'Go Down, Death:

"On Thanksgiving Day, 1926, I was at home.

After breakfast I went to my desk and began

work in earnest on the poem. As I worked, my

own spirit rose till it reached a degree almost of

ecstasy. The poem shaped itself easily and before the hour for dinner I had written it as it

stands published."

go.hrw.com

736

THE MODERNS

LEO 11-15

Before You Read

Go DOWN, DEATH

Make the Connection

Death at the Doorstep

Every religion has its own view of

what happens when we die, and

countless storytellers, philosophers, and writers have added

their views to the sum of our understanding of the great mystery

we call death. Is death a source

of pain and sorrow, or is it a

comfort-perhaps even a joyous

affirmation of life?

Reading Skills

and Strategies

Go Down, Death

A Funeral Sermon

James Weldon Johnson

Weep not, weep not,

She is not dead;

She's resting in the bosom of Jesus.

Heart-broken husband-weep no more;

5 Grief-stricken son- weep no more;

Left-lonesome daughter-weep no more;

She's only just gone home.

~~

W:w,

Tracking Your Responses

This poem is one of seven "sermons" written by Johnson in the

style of the old-time African

American preachers. He collected the sermons in a book

called God's Trombones-the

trombone being "of just the tone

and timbre to represent the oldtime Negro preacher's voice."

Johnson tells us that the person reading "Go Down, Death"

would intone, moan, plead, blare,

crash, and thunder. As you read,

jot down the words, lines, or

stanzas that have the strongest

emotional effect on you.

Elements of Literature

Personification

Personification is a figure of

speech in which an animal, object, or abstract concept is portrayed with human qualities. In

this poem, Johnson invites readers to see and understand Death

as a character rather than as an

abstract concept.

10

15

20

Day before yesterday morning,

God was looking down from his great, high heaven,

Looking down on all his children,

And his eye fell on Sister Caroline,

Tossing on her bed of pain.

And God's big heart was touched with pity,

With the everlasting pity.

And God sat back on his throne,

And he commanded that tall, bright angel standing at his right

hand:

Call me Death!

And that tall, bright angel cried in a voice

That broke like a clap of thunder:

Call Death! -Call Death!

And the echo sounded down the streets of heaven

Till it reached away back to that shadowy place,

Where Death waits with his pale, white horses. o

And Death heard the summons,

And he leaped on his fastest horse,

Pale as a sheet in the moonlight.

Up the golden street Death galloped,

And the hoofs of his horse struck frre from the gold,

But they didn't make no sound.

30 Up Death rode to the Great White Throne,

And waited for God's command.

25

And God said: Go down, Death, go down,

Go down to Savannah, Georgia,

Down in Yamacraw,

23. Death waits ... horses: allusion to Revelation 6:8,

"And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that

sat on him was Death."

jAMES WELDON jOHNSON

73 7

·al!UOS~W UO I!Q ·s~~~noa UOJ~'v'

SNli3COW 3HJ.

8 [£

Aq (L'Z:61) I.JlDaQ UMOQ 09

And fmd Sister Caroline.

She's borne the burden and heat of the day,

She's labored long in my vineyard,

And she's tiredShe's weary40 Go down, Death, and bring her to me.

35

And Death didn't say a word,

But he loosed the reins on his pale, white horse,

And he clamped the spurs to his bloodless sides,

And out and down he rode,

45 Through heaven's pearly gates,

Past suns and moons and stars;

On Death rode,

And the foam from his horse was like a comet in the sky;

On Death rode,

50 Leaving the lightning's flash behind;

Straight on down he came.

While we were watching round her bed,

She turned her eyes and looked away,

She saw what we couldn't see;

55 She saw Old Death. She saw Old Death

Coming like a falling star.

But Death didn't frighten Sister Caroline;

He looked to her like a welcome friend.

And she whispered to us: I'm going home,

60 And she smiled and closed her eyes.

And Death took her up like a baby,

And she lay in his icy arms,

But she didn't feel no chill.

And Death began to ride again65 Up beyond the evening star,

Out beyond the morning star, a

Into the glittering light of glory,

On to the Great White Throne.

And there he laid Sister Caroline

70 On the loving breast of Jesus.

And Jesus took his own hand and wiped away her tears,

And he smoothed the furrows from her face,

And the angels sang a little song,

And Jesus rocked her in his arms,

75 And kept a-saying: Take your rest,

Take your rest, take your rest.

'

66. evening star ... morning

star: the planet Venus, which is traditionally referred to as both the morning star and the evening star. Its

orbital path makes it visible for no

more than about three hours after

sunset and three hours before

sunrise.

Weep not-weep not,

She is not dead;

She's resting in the bosom of Jesus.

jAMES WELDON jOHNSON

739

God's Trombones

~

In his preface to God's Trombones, from which "Go Down, Death" is taken,

: Johnson describes the origin of his idea for his collection of poems.

I

The old-time preacher was generally a man far

above the average in intelligence; he was, not

infrequently, a man of positive genius. The earliest of these preachers must have virtually

committed many parts of the Bible to memory

through hearing the scriptures read or

preached from in the white churches which

the slaves attended. They were the flrst of the

slaves to learn to read, and their reading was

confmed to the Bible, and specillcally to the

more dramatic passages of the Old Testament.

A text served mainly as a starting point and

often had no relation to the development of the

sermon. Nor would the old-time preacher balk

at any text within the lids of the Bible. There is

the story of one who after reading a rather

cryptic passage took off his spectacles, closed

the Bible with a bang and by way of preface

said, "Brothers and sisters, this morning-! intend to explain the unexplainable-fmd out

the undefmable-ponder over the imponderable-and unscrew the inscrutable."

The old-time Negro preacher of parts was

above all an orator, and in good measure an

actor. He knew the secret of oratory, that at

bottom it is a progression of rhythmic words

more than it is anything else. Indeed, I have

witnessed congregations moved to ecstasy by

the rhythmic intoning of sheer incoherencies.

He was a master of all the modes of eloquence.

He often possessed a voice that was a marvelous instrument, a voice he could modulate

from a sepulchral whisper to a crashing thunder clap. His discourse was generally kept at a

high pitch of fervency, but occasionally he

dropped into colloquialisms and, less often,

740

THE MODERNS

into humor. He preached a personal and anthropomorphic God, a sure-enough heaven

and a red-hot hell. His imagination was bold

and unfettered. He had the power to sweep his

hearers before him; and so himself was often

swept away. At such times his language was

not prose but poetry. It was from memories of

such preachers there grew the idea of this

book of poems.

-James Weldon Johnson

Prayer Meeting ( 1951) by Samella Sanders Lewis.

Watercolor (I r

X

14%").

Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia.

Connections

A

POEM

: Borrowing from the spiritual "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," the African Ameri) creates a poem that also has the

: can poet Gwendolyn Brooks ( 1917i rhythm of a song. (For more on spirituals, see page 432.) Lincoln Cemetery is

: in Chicago.

of De Witt Williams on his

way to Lincoln Cemetery

Gwendolyn Brooks

He was born in Alabama.

He was bred in Illinois.

He was nothing but a

Plain black boy.

5 Swing low swing low sweet sweet chariot.

Nothing but a plain black boy.

Drive him past the Pool Hall.

Drive him past the Show.

Blind within his casket,

10 But maybe he will know.

Down through Forty-seventh Street:

Underneath the L,

And-Northwest Corner, Prairie,

That he loved so well.

Haitian Funeral Procession (c. 1950s) by Ellis Wilson.

Oil on canvas (30 W' x 29 1f4").

Aaron Douglas Collection, Amistad Research Center,

Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

15 Don't forget the Dance Halls-

Warwick and Savoy,

Where he picked his women, where

He drank his liquid joy.

20

Born in Alabama.

Bred in Illinois.

He was nothing but a

Plain black boy.

Swing low swing low sweet sweet chariot.

Nothing but a plain black boy.

jAMES WELDON jOHNSON

741

-

MAKING MEANINGS

justified, but I was taken aback. I got out my

copy of Leaves of Grass and read him some of

the things I admired most. There was, at

least, some personal consolation in the fact

that his verdict was the same on Whitman

himself.

First Thoughts

I. Review the notes you made as you read ~

"Go Down, Death:' Which words, lines,

'--' ,

or stanzas had the strongest effect on you? Why?

- James Weldon Johnson

Shaping Interpretations

l

2. Identify where God is in stanza 2, and where

Death is in stanza 3. According to stanza 5,

where is Sister Caroline? How does Sister Caroline respond to Death's arrival in stanza 7?

3. Find three similes that help to suggest the magnificence of the workings of heaven.

4. Does the speaker portray God and Jesus as distant, forbidding figures, or as familiar, gentle

ones? Point out at least four details that support your interpretation.

5. Why do you think Death rides a "pale, white

horse"? Where else have you seen the color

white used in a similar symbolic way?

I

Examine "Go Down, Death;' and see if you can

identify the influence of Whitman (page 348). Look

for these elements of Whitman's style: (I) repetition and parallel structure to create rhythm;

(2) the simple language of everyday conversation, including slang; (3) variation of line length, from very

long to very short, to create a rolling cadence;

(4) other sound effects.

CHOICES:

Building Your Portfolio

Extending the Text

Writer's Notebook

6. While many of the traditional representations of

death are fearful, the one in this poem is not.

Discuss the ways Johnson personifies death in

this poem. Then compare Johnson's image with

images you have encountered in literature (see

especially Emily Dickinson's "Because I could not

stop for Death" on page 391) or on film.

1. Collecting Ideas for an

ELEMENTS OF

LITERATURE

Free Verse and the Orator's Style

I sho~ed Paul the things I had done under the

sudden influence of Whitman. He read them

through and, looking at me with a queer

smile, said, "I don't like them, and I don't see

what you are driving at." He may have been

-THE MODERNS

Explore the similarities and

differences in the attitudes toward death in

Johnson's "Go Down, Death" and Gwendolyn

Brooks's "of De Witt Williams on his way

to Lincoln Cemetery" (see Connections on

page 741 ). Take notes in a double-column

comparison-contrast chart. Save your notes

for possible use in the Writer's Workshop

on page 804.

Comparing Sermons

When Johnson was working on the poems that

would eventually become God's Trombones, he talked

with the African American poet Paul Laurence

Dunbar ( 1872-1906).

742

Interpretive Essay

2. Sermons Side by Side

Extracts from another famous sermon in

American literature are on page 79-Jonathan

Edwards's "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry

God." In a brief essay, compare and contrast

Johnson's sermon with Edwards's. Consider

these elements of each sermon: (a) imagery,

(b) figures of speech, (c) message, (d) tone,

(e) audience, and (f) purpose.

~

1

Claude McKay ( 1941) by Carl Van Vechten.

The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New

Haven, Connecticut. Estate of Carl Van Vechten, Joseph Solomon,

Executor.

Claude McKay

(1890-1948)

C

laude McKay was born and raised on the

Caribbean island of Jamaica, the eighth

child of farmers. When he was nine, he went to

live with his eldest brother, who was a schoolmaster, and his early education came chiefly

from his brother's classroom and library. McKay

apprenticed as a wheelwright and cabinetmaker,

then worked as a constable. All the while, he

was writing poems in a Jamaican dialect of

English. In 1912, with the help of an English

friend, he published his first two collections of

verse, Songs ofjamaica and Constab Ballads, then

traveled to the United States to study agriculture. After briefly enrolling at Tuskegee Institute

in Alabama, McKay transferred to Kansas State

College, where he studied for two years.

In 1914, McKay moved to Harlem and

opened a restaurant with a friend. When this

venture failed, he supported himself with a variety of jobs, from janitor to butler, while he continued to refine his craft and publish poems in

periodicals. In 1920, his third book, Spring in

New Hampshire, was published. His most important book of poetry, Harlem Shadows, appeared

in 1922.

By this time, McKay was a major figure in the

Harlem Renaissance. He had served as an editor of the radical newspapers the Liberator and

The Masses. Like many writers of the period, he

was drawn to the "noble experiment" of communism. In 1922, he signed on as a stoker for a

merchant ship and toured Russia for a year.

McKay lived abroad, principally in France,

until 1934. During this time he concentrated on

writing fiction and essays rather than poetry,

and he published four novels, including the bestselling Home to Harlem ( 1928). Disillusioned

with communism, in 1942 he converted to

Roman Catholicism. McKay spent the rest of his

life teaching in Catholic schools in Chicago.

Despite the use of Jamaican dialect early in

his career, much of McKay's poetry shows the

influence of the English Romantic poets, especially Wordsworth, Keats, and Shelley. In subject matter, however, the Romantics and McKay

diverge widely: McKay's sonnets voice his ambivalent and often defiant feelings about African

American life in the United States.

go.hrw.com

LEOJJ-15

CLAUDE McKAY

743

Before

You Read

AMERICA

z

~

Make the Connection

()"

::J

!!!..

:I

5;

America the Beautiful?

By expressing defiance as well as

love, McKay reveals the complexity of the African American experience in the United States-an

experience that requires a large

measure of strength and courage.

Ill

c:

3

a)>

3

~

;:;·

I»

::J

)>

~

~

e:;;r-

:;·

~

Quickwrite

0

?

0

•

0

Write down four or five

%.:0

adjectives that you feel describe the heart of today's American society. Then, in two or

three sentences, tell how you

see yourself in relation to that

society.

()

0

c:

;:I

c:

"<

)>

;:I

;>:l

c:0

c:

(l

_Ill

z

:-<

Lower East Side from Scenes of New York (Mural study, Madison

Square Postal Station, New York City) by Kindred Mcleary.

Tempera on fiberboard (233/4" x 20").

America

Claude McKay

Although she feeds me bread of bitterness, o

And sinks into my throat her tiger's tooth,

Stealing my breath of life, I will confess

I love this cultured hell that tests my youth!

5 Her vigor flows like tides into my blood,

Giving me strength erect against her hate.

Her bigness sweeps my being like a flood.

Yet as a rebel fronts o a king in state,

I stand within her walls with not a shred

10 Of terror, malice, not a word of jeer.

Darkly I gaze into the days ahead,

And see her might and granite wonders there,

Beneath the touch of Time's unerring hand,

Like priceless treasures sinking in the sand.

1. bread of bitterness: allusion to Psalm 80:5, "Thou

feedest them with the bread of tears; and givest them

tears to drink in great measure."

8. fronts: confronts.

744

THE MODERNS

~

MAKING MEANINGS

CHOICES:

Building Your Portfolio

First Thoughts

I. Review your Quickwrite. Then, compare •

your views of America, and your place in

it, with McKay's.

Writer's Notebook

1. Collecting Ideas for

an Interpretive Essay

Shaping Interpretations

2. In lines 1-3, what treatment does the poem's

speaker say he receives from America? What

qualities of America cause the speaker to love

the country anyway?

3. America is personified in this poem as an entity

both cruel and powerful. What images suggest

America's cruelty and injustice? What images

convey its power?

4. A rebel with "not a shred I Of terror, malice, not

a word of jeer" might seem to be a rebel who

does not really rebel. How does the poem resolve this paradox, or apparent contradiction?

Using a chart like the one

below, compare McKay's "America" to

Robinson jeffers's "Shine, Perishing Republic"

(page 581 ). Consider the form, subject,

point of view, and tone of each poem. List

similarities in the overlapping space. Use the

remaining spaces to list the differences. Save

your notes for possible use with the Writer's

Workshop on page 804.

Extending the Text

5. What does this speaker see happening to America as he gazes into "the days ahead"? What messages about America's future do you hear today

in various sources-films, TV shows, news programs, magazines, and other media?

Street vendors in Harlem in the

1920s.

UPI/Bettmann.

Creative Writing I Art

2. Get the Message

Design a poster or write a bumper sticker

that the speaker in "America" might display.

Try to capture in a phrase or two the main

idea expressed in the poem.

z

~

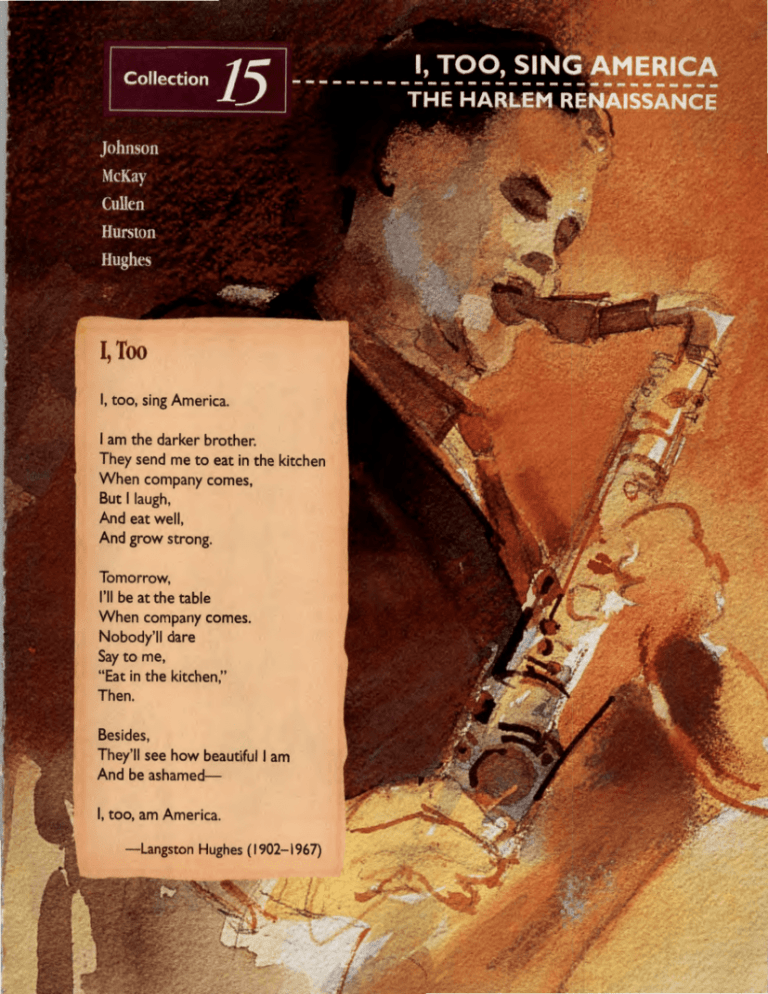

Countee Cullen

()"

:>

!!!..

00

:4

(1903-1946)

ountee Cullen grew up in New York City

as the adopted son of Rev. and Mrs. Frederick Cullen. He was a brilliant student, and

during high school he was already writing accomplished poems in traditional forms. He

graduated Phi Beta Kappa from New York University in 1925. While in college, Cullen won

the Witter Bynner Poetry Prize; that same year,

Color, his first volume of poetry, was published.

This collection won a gold medal from the Harmon Foundation and established the young

poet's reputation.

After earning his master's degree from Harvard in 1926, Cullen worked as an assistant

editor of the important African American magazine Opportunity. His poems were published in

such influential periodicals as Harper's, Poetry,

and Crisis. In 1927, he published Copper Sun, a

collection of poems, and Caroling Dusk, an anthology of poetry by African Americans. Caroling Dusk was a significant contribution to the

Harlem Renaissance, but the introduction

Cullen wrote for the book was controversial.

He called for black poets to write traditional

verse and to avoid the restrictions of solely

racial themes.

At the peak of his career, Cullen married the

daughter of the famous black writer W.E.B.

Du Bois and published a third collection of

poems, The Ballad ofthe Brown Girl. In 1929, he

published a fourth volume, The Black Christ.

Although he continued to write prose until

the end of his life, this was his last collection of

poetry. During the Great Depression of the

1930s, unable to make a living solely from writing, he began teaching in Harlem public schools,

a job that he held until his early death.

~-

C\

!!!..

iD

C

~

VI

~- ~

:>"VI

"'0

3 ::1.

"'"'

R:.

:r.a

~ ~·

O<IC:

iJ

a~

3VI

... :r,

=>":>

(I)~

Zo

g.c,

"':>

~0

!:r0.

c..;:r

~~

3f;

~ .,

~

...

O'gJ

"'n

r+(i)

ir;r>

)>"TI

a[

. n

():>"

0 3

c:"'

;4:>

(I)"'

VI:>

'<c..

)>I

:4o

;;c~

(I) I»

VI -,

oc..

~~

!D;J,

z~

:-<m

Countee Porter Cullen (c. 1925) by Winold Reiss.

Pastel on artist board (30 111{ x 211ft).

Cullen's verse was heavily influenced by the

poetry of the English Romantics, especially John

Keats. He thought of himself primarily as a lyric

poet in the Romantic tradition, not as a black

poet writing about social and racial themes. Nevertheless, Cullen found himself repeatedly drawn

to such themes: "Somehow or other I find my

poetry of itself treating of the Negro, of his joys

and his sorrows-mostly of the latter-and of

the heights and depths of emotion which I feel as

a Negro:•

go.hrw.com

746

THE MODERNS

!:!.

:> 0

rt?

LEO 11 -15

I

~

j

~

I

l

Before You Read

TABLEAU

Make the Connection

Still Life

Usually, tableau means a scene or

an action stopped cold, like a still

picture in a reel of film. Here we

have a tableau vivant; that is, a little scene in which figures silently

pose, a significant moment

caught and preserved. This preserved moment is a disarmingly

simple glimpse of a friendship-a

friendship that speaks silently but

forcefully of a much larger issue.

Quickwrite

~

If you were sure you

: ;: : ; \

were behaving correctly,

how would you deal with critics

of your actions? Write down

your thoughts in a few sentences.

Tableau

(For Donald Duff)

Countee Cullen

Locked arm in arm they cross the way,

The black boy and the white,

The golden splendor of the day,

The sable pride of night.

5 From lowered blinds the dark folk stare,

And here the fair folk talk,

Indignant that these two should dare

In unison to walk.

10

Oblivious to look and word

They pass, and see no wonder

That lightning brilliant as a sword

Should blaze the path of thunder.

~

c:

co

"'

~

_g

(II

~

"·=

(;j

1..:)

>.

c:

~

COUNTEE CULLEN

747

Before

You Read

INCIDENT

Make the Connection

A Word Remembered

The power of a word to taunt,

to criticize, to dehumanize can't

be underestimated. You might be

shaken by the offensive word in

this poem-imagine how it

would affect a child.

Quickwrite

•

Before you read "lnci~'

dent," quickwrite your

response to the poem's title.

Does it suggest something serious, or something relatively

minor? How would you react if

the title were "Catastrophe"?

Passengers ( 1953) by Raphael Soyer. Oil on canvas.

© Estate of Raphael Soyer, Forum Gallery, New York.

Incident

Countee Cullen

Once, riding in old Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-ftlled with glee,

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me.

s Now I was eight and very small,

And he was no whit bigger,

And so I smiled, but he poked out

His tongue, and called me "Nigger."

10

748

THE MODERNS

I saw the whole of Baltimore

From May until December;

Of all the things that happened there

That's all that I remember.

j

MAKING MEANINGS

CHOICES:

Building Your Portfolio

Tableau

First Thoughts

I. Review your Quickwrite. Do the boys in ~

"Tableau" act toward their critics as you ~

would act toward yours?

Shaping Interpretations

2. What metaphors describe the two boys in the

first stanza?

3. In the third stanza, who or what is "lightning

brilliant as a sword"? Who or what is the "path

of thunder"?

4. Why should such a commonplace thing as the

friendship between two boys evoke such a dramatic response? What larger topic do you think

the poem is really about?

Incident

First Thoughts

I. Look at your Quickwrite notes. Does the

poem describe a mere incident or something much larger? Explain.

~

W

Shaping Interpretations

2. What might lead a child to insult an eight-yearold boy in the way described here? In what ways

is a child's prejudice even more disturbing than

an adult's?

3. Review your response to First Thoughts. What

ironic overtones does the title have?

4. The speaker never directly states his emotional

response to the experience. How does the last

stanza indirectly make clear the impact the event

had on him?

Extending the Text

1. Collecting Ideas for an

Interpretive Essay

Compare and contrast the

diction and sentence structure in "Tableau" and "Incident."

~

Take notes that show how Cullen uses language to create two different effects in poems

that are about very similar subjects. Save your

notes for possible use in the Writer's Workshop on page 804.

Creative Writing

2. Kindred Spirits

Write a conversation in which the two boys

who appear in "Tableau" discuss what happens in "Incident" with the eight-year-old boy

who was the victim of the incident.

Creative Writing I Music

3. AFilm Version

Suppose you were going to make a short film

based on the poem "Incident." To convince a

producer that you have a good idea, write a

list of planned camera shots, in the

order in which they would appear on screen. Then

write a treatment, or

summary, of your vision

of the film. If you wish,

find or compose music

that you would use as an

appropriate soundtrack

for your film, and include

a recording of that music

with your film treatment.

5. Do you think that the content and message of

"Tableau" and "Incident" are outdated, or are

the scenes described in these poems still occurring today? Explain.

COUNTEE CULLEN

749

Zora Neale Hurston

a scholar's eye to evaluate oral tales, many of

which were familiar to her from earliest childhood. Eventually, she gathered enough folklore

(c. 1903-1960)

to fill two groundbreaking collections, Mules

and Men ( 1935) and Tell My Horse ( 1938). Alice

ora Neale Hurston was born in the all-black

Walker (page I I 0 I) says that the stories in

town of Eatonville, Florida. Her father was a

Mules and Men gave back to her own relatives in

preacher, and her mother, a schoolteacher, urged

the South all the stories they'd forgotten or

her talented daughter to "jump at the sun:'

grown ashamed of.

In her autobiography, Hurston recalls that as

a young girl, "I used to climb to the top of one

Hurston also wrote musical revues portraying black folk-culture, and these brought her iniof the huge chinaberry trees which guarded our

front gate and look out over

tial success. But it was Story

the world. The most interestmagazine's publication of her

ing thing that I saw was the

short story "The Gilded Six

horizon .... It grew upon me

Bits" that launched her literary

that I ought to walk out to the

career. When the Philadelphia

horizon and see what the end

publisher J. B. Lippincott asked

of the world was like."

if she had a novel, Hurston

When Hurston was about

promptly sat down and wrote

nine, her mother died, and

Jonah's Gourd Vine, published in

Zora was passed among rela1934. Three years later,

tives and family friends, supHurston published her best

porting herself from her early

novel, Their Eyes Were Watching

teens on. Eventually, she enGod, the story of a young

rolled at Howard University in

African American woman who

Washington, D.C., where she

strikes out for a life beyond a

published her first story in 1921.

conventional marriage, much as

Four years later, she set out

Hurston herself had done.

Zora Neale Hurston ( 1935) by Carl

for New York City to attend

Throughout the last twenty

Barnard College, arriving with Van Yechten.

years of her life, Hurston continued to produce fiction and nonfiction, includa dollar and a half in her pocket. Hurston was

soon in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance,

ing her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road.

But she began to have difficulty finding a market

writing stories and plays that celebrated her

African American heritage. She wore big hats

for her work, some of which was criticized in

and turbans, danced, gave parties, and somethe African American community for celebrattimes shocked other African American artists,

ing the life of black people in the United States

rather than confronting the white community

especially male writers like James

for its discrimination.

Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes.

In the late 1940s, Hurston left New York and

Enrolling at prestigious Barnard College,

returned to Florida. In 1960, she died, broke, in

Hurston met the famous anthropologist Franz

a Florida welfare home. A collection had to be

Boas. Boas believed that Hurston's interest was

taken up to pay for her funeral. Ironically, in the

really in his field, the study of human social and

years since her death, much of her work has

cultural behavior. Indeed, Hurston, who became

been brought back into print, and Hurston is

his protege, did eventually make her reputation

now recognized as the forerunner of such celenot just as a fiction writer, but also as a folklorist. She traveled through Alabama, Florida,

brated contemporary writers as Toni Morrison

and Alice Walker.

and Louisiana to gather folklore material, using

Z

go.hrw.com

750

THE MODERNS

LEOll-15

Before You Read

FROM

DUST TRACKS ON A ROAD

Make the Connection

Looking for the Threads

It's no surprise that the autobiographies of writers often include lovingly detailed memories

of childhood interests and discoveries that paved the way for

the adult writer. In her autobiography, One Writer's

Beginnings, Eudora Welty (page

633) notes, "Writing fiction has

developed in me an abiding respect for the unknown in a

human lifetime and a sense of

where to look for the threads,

how to follow, how to connect,

find in the thick of the tangle

what clear line persists. The

strands are all there: To the

memory nothing is ever really

lost." Here, Zora Neale Hurston

connects some of her own

threads by recounting what is

surely every writer's first experience of falling in love: the passion

for hearing and reading stories.

Reading Skills

and Strategies

well as personal insight and data.

Woven through these recollections of Hurston's childhood are

her impressions of racial segregation, economic conditions, education, social customs, and family,

as well as general attitudes of

Southerners around 1900.

I

uredto tWa,

!ME Dlt/ tDf' of

~Jah[HJ!t

ltltdwaeck~

worldJoby.

-i

:r

(I)

:I

~

a

"'0

Q..

g·

:I

~

(I)

c

3

g,

>

>

~

~

:r

!!;

I

0

"'0

"'0

0

n

7'

I

~::J

-n

c

tzi

::J

F-e

V1

0

V1

0

Analyzing an Autobiography

iv

.:;;

.,:r

As you read, write down what

you learn about Hurston's character from her thoughts and

actions, as well as any details that

suggest Hurston's early interest

in people, her fascination with

storytelling, and her later devotion to anthropology and folklore

research.

]

~:r

@

..c

(X)

IV

-i

:r

(I)

:I

~

a

"'0

Q..

s·

::J

:I

~

(I)

c

Background

Zora Neale Hurston's Dust

Tracks on a Road is rich with cultural and historical meaning, as

3

g,

>

?

Her World ( 1948) by Philip Evergood. Oil on canvas (48" x 35%'}

ZORA NEALE HURSTON

75 I

I

used to take a seat on top of the gatepost and

watch the world go by. One way to Orlando

ran past my house, so the carriages and cars

would pass before me. The movement made

me glad to see it. Often the white travelers

would hail me, but more often I hailed them,

and asked, "Don't you want me to go a piece of

the way with you?"

They always did. I

know now that I must

s~hadklwum

have caused a great

deal of amusement

among them, but my

must

self-assurance

have carried the point,

br~rWM

for I was always invited

to come along. I'd ride

~~.

up the road for perhaps

a half-mile, then walk

back. I did not do this with the permission of

my parents, nor with their foreknowledge.

When they found out about it later, I usually

got a whipping. My grandmother worried

about my forward ways a great deal. She had

known slavery and to her my brazenness was

unthinkable.

"Git down offa dat gatepost! You li'l sow,

you! Git down! Setting up dere looking dem

1

white folks right in de face! They's gowine to

lynch you, yet. And don't stand in dat doorway

gazing out at 'em neither. Youse too brazen to

live long."

;!Avery aJtd to

Ito my

1. gowine: dialect for "going."

WORDS TO OWN

hail (hal) v.: greet.

brazenness (bra'zan · nis) n.: boldness.

Nevertheless, I kept right on gazing at them,

and "going a piece of the way" whenever I could

make it. The village seemed dull to me most of the

time. If the village was singing a chorus, I must

have missed the tune.

2

Perhaps a year before the old man died, I came

to know two other white people for myself. They

were women.

It came about this way. The whites who came

down from the North were often brought by their

friends to visit the village school. A Negro school

was something strange to them, and while they

were always sympathetic and kind, curiosity must

have been present, also. They came and went,

came and went. Always, the room was hurriedly

put in order, and we were threatened with a

prompt and bloody death if we cut one caper

while the visitors were present. We always sang a

spiritual, led by Mr. Calhoun himself. Mrs. Calhoun always stood in the back, with a palmetto

switch 3 in her hand as a squelcher. We were all little angels for the duration, because we'd better

4

be. She would cut her eyes and give us a glare

that meant trouble, then turn her face toward the

visitors and beam as much as to say it was a great

privilege and pleasure to teach lovely children like

us. They couldn't see that palmetto hickory in her

hand behind all those benches, but we knew

where our angelic behavior was coming from.

Usually, the visitors gave warning a day ahead

and we would be cautioned to put on shoes,

comb our heads, and see to ears and fmgernails.

There was a close inspection of every one of us

before we marched in that morning. Knotty

heads, dirty ears, and fmgernails got hauled out of

line, strapped, and sent home to lick the calf 5

over again.

This particular afternoon, the two young ladies

just popped in. Mr. Calhoun was flustered, but he

put on the best show he could. He dismissed the

class that he was teaching up at the front of the

room, then called the flfth grade in reading. That

was my class.

2. old man: a white farmer who knew Hurston's

family, took her fishing, and gave her advice.

3. palmetto switch: whip made from the stem of a large,

fanlike leaf of a kind of palm tree. Teachers sometimes

used these switches to discipline students.

4. cut her eyes: slang for "look scornfully."

5. lick the calf: slang for "wash up."

754

THE MODERNS

So we took our readers and went up front. We

stood up in the usual line, and opened to the lesson. It was the story of Pluto and Persephone. 6 It

was new and hard to the class in general, and Mr.

Calhoun was very uncomfortable as the readers

stumbled along, spelling out words with their

lips, and in mumbling undertones before they exposed them experimentally to the teacher's ears.

Then it came to me. I was ftfth or sixth down

the line. The story was not new to me, because I

had read my reader through from lid to lid, the

frrst week that Papa had bought it for me.

That is how it was that my eyes were not in the

book, working out the paragraph which I knew

would be mine by counting the children ahead of

me. I was observing our visitors, who held a book

between them, following the lesson. They had

shiny hair, mostly brownish. One had a looping

gold chain around her neck. The other one was

dressed all over in black and white with a pretty

fmger ring on her left hand. But the thing that

held my eyes were their fmgers. They were long

and thin, and very white, except up near the tips.

There they were baby pink. I had never seen such

hands. It was a fascinating discovery for me. I

wondered how they felt. I would have given those

hands more attention, but the child before me

was almost through. My turn next, so I got on my

mark, bringing my eyes back to the book and

made sure of my place. Some of the stories I had

reread several times, and this Greco-Roman myth

was one of my favorites. I was exalted by it, and

that is the way I read my paragraph.

"Yes, Jupiter7 had seen her (Persephone). He

had seen the maiden picking flowers in the fleld.

He had seen the chariot of the dark monarch

pause by the maiden's side. He had seen him

when he seized Persephone. He had seen the

6. Pluto and Persephone (p;)r · sef';) · ne): In classical

mythology, Pluto, or Hades, is the god who rules the underworld; Persephone, also known as Proserpina, is his

wife, queen of the underworld. In this version of the origin of the seasons, Hurston uses the names of Roman and

Greek gods interchangeably.

7. Jupiter: in Roman mythology, king of the gods.

WORDS TO OWN

caper (ka'par) n.: foolish prank.

exalted (eg · zolt'id) v.: lifted up.

black horses leap down Mount Aetna's8 fiery

held out those flower-looking fmgers toward me.

throat. Persephone was now in Pluto's dark realm

I seized the opportunity for a good look.

and he had made her his wife."

"Shake hands with the ladies, Zora Neale," Mr.

The two women looked at each other and then

Calhoun prompted and they took my hand one

back to me. Mr. Calhoun broke out with a proud

after the other and smiled. They asked me if I

smile beneath his bristly moustache, and instead

loved school, and I lied that I did. There was some

of the next child taking up where I had ended, he

truth in it, because I liked geography and reading,

nodded to me to go on. So I read the story to the

and I liked to play at recess time. Whoever it was

end, where flying Mercury, the messenger of the

invented writing and arithmetic got no thanks

Gods, brought Persephone

from me. Neither did I like

back to the sunlit earth and

the arrangement where

restored her to the arms of

the teacher could sit up

Dame Ceres, her mother,

there with a palmetto

that the world might have

stem and lick me whenspringtime and summer

ever he saw fit. I hated

flowers, autumn and harthings I couldn't do anything about. But I knew

vest. But because she had

bitten the pomegranate

better than to bring that

while in Pluto's kingdom,

up right there, so I said

she must return to him for

yes, I loved school.

three months of each year,

"I can tell you do,"

Brown Taffeta gleamed.

and be his queen. Then the

She patted my head, and

world had winter, until she

~ laAi,u

returned to earth.

was lucky enough not to

The class was dismissed and the

get sandspurs in her hand. Chilou& thor~

visitors smiled us away and went

dren who roll and tumble in the

into a low-voiced conversation with

grass in Florida are apt to get

Mr. Calhoun for a few minutes.

sandspurs in their hair. They

shook hands with me again and

They glanced my way once or twice

~err toward flU,.

I went back to my seat.

and I began to worry. Not only was I

When school let out at three

barefooted, but my feet and legs

o'clock, Mr. Calhoun told me to wait. When

were dusty. My hair was more uncombed than

everybody had gone, he told me I was to go to the

usual, and my nails were not shiny clean. Oh, I'm

Park House, that was the hotel in Maitland, the

going to catch it now. Those ladies saw me, too.

next

afternoon to call upon Mrs. Johnstone and

Mr. Calhoun is promising to 'tend to me. So I

Miss Hurd. I must tell Mama to see that I was clean

thought.

and brushed from head to feet, and I must wear

Then Mr. Calhoun called me. I went up thinkshoes and stockings. The ladies liked me, he said,

ing how awful it was to get a whipping before

and I must be on my best behavior.

company. Furthermore, I heard a snicker run over

The next day I was let out of school an hour

the room. Hermie Clark and Stell Brazzle did it out

early, and went home to be stood up in a tub of

loud, so I would be sure to hear them. The smart

suds and be scrubbed and have my ears dug into.

aleck was going to get it. I slipped one hand beMy sandy hair sported a red ribbon to match

hind me and switched my dress tail at them, indimy red and white checked gingham dress,

cating scorn.

starched until it could stand alone. Mama saw to it

"Come here, Zora Neale," Mr. Calhoun cooed as

that my shoes were on the right feet, since I was

I reached the desk. He put his hand on my shoulder and gave me little pats. The ladies smiled and

rHfi.Lut

4ltli held

JlDwer,IIJo!Wtj

WORDS TO OWN

8. Mount Aetna's: Mount Aetna (also spelled Etna) is a

volcanic mountain in eastern Sicily.

realm (relm) n.: kingdom.

ZORA NEALE HURSTON

755

careless about left and right. Last thing, I was

given a handkerchief to carry, warned again

about my behavior, and sent off, with my big

brother John to go as far as the hotel gate with me.

First thing, the ladies gave me strange things,

like stuffed dates and preserved ginger, and encouraged me to eat all that I wanted. Then they

showed me their Japanese dolls and just talked. I

was then handed a copy of Scribner's Magazine,

and asked to read a place that was pointed out to

me. After a paragraph or two, I was told with

smiles, that that would do.

I was led out on the grounds and they took my

picture under a palm tree. They handed me what

was to me then a heavy cylinder done up in

fancy paper, tied with a ribbon, and they told me

goodbye, asking me not to open it until I got

home.

My brother was waiting for me down by the

lake, and we hurried home, eager to see what

was in the thing. It was too heavy to be candy or

anything like that. John insisted on toting it for

me.

My mother made John give it back to me and

let me open it. Perhaps, I shall never experience

such joy again. The nearest thing to that moment

was the telegram accepting my frrst book. One

hundred goldy-new pennies rolled out of the

cylinder. Their gleam lit up the world. It was not

avarice that moved me. It was the beauty of the

thing. I stood on the mountain. Mama let me play

with my pennies for a while, then put them away

for me to keep.

That was only the beginning. The next day I

received an Episcopal hymnbook bound in white

leather with a golden cross stamped into the

front cover, a copy of The Swiss Family Robinson, and a book of fairy tales.

I set about to commit the song words to memory. There was no music written there, just the

words. But there was to my consciousness music

in between them just the same. "When I survey

the Wondrous Cross" seemed the most beautiful

to me, so I committed that to memory first of all.

Some of them seemed dull and without life, and I

pretended they were-not there. If white people

liked trashy singing like that, there must be

something funny about them that I had not noticed before. I stuck to the pretty ones where the

words marched to a throb I could feel.

756

THE MODERNS

Of~greek~

~euler HUJv-ed

HUJrt.

WORDS TO OWN

avarice (av' a· ris) n.: greed.

HU!,-

A month or so after the two young ladies returned to Minnesota, they sent me a huge box

packed with clothes and books. The red coat with

a wide circular collar and the red tam pleased me

more than any of the other things. My chums pretended not to like anything that I had, but even

then I knew that they were jealous. Old Smarty

had gotten by them again. The clothes were not

new, but they were very good. I shone like the

morning sun.

But the books gave me more pleasure than the

clothes. I had never been too keen on dressing

up. It called for hard scrubbings with Octagon

soap suds getting in my eyes, and none too gentle

fmgers scrubbing my neck and gouging in my

ears.

In that box were Gulliver's Travels, Grimm's

Fairy Tales, Dick Whittington, Greek and

Roman Myths, and best of all, Norse Tales. Why

did the Norse tales strike so deeply into my soul? I

do not know, but they did. I seemed to remember

seeing Thor swing his mighty short-handled hammer as he sped across the sky in rumbling thunder, lightning flashing from the tread of his steeds

and the wheels of his chariot. The great and good

Odin, who went down to the well of knowledge

to drink, and was told that the price of a drink

from that fountain was an eye. Odin drank deeply,

then plucked out one eye without a murmur and

handed it to the grizzly keeper, and walked away.

That held majesty for me.

Of the Greeks, Hercules moved me most. I followed him eagerly on his tasks. The story of the

choice of Hercules as a boy when he met Pleasure

and Duty, and put his hand in that of Duty and followed her steep way to the blue hills of fame and

glory, which she pointed out at the end, moved

me profoundly. I resolved to be like him. The

tricks and turns of the other gods and goddesses

left me cold. There were other thin books about

this and that sweet and gentle little girl who gave

up her heart to Christ and good works. Almost always they died from it, preaching as they passed. I

was utterly indifferent to their deaths. In the first

place I could not conceive of death, and in the

next place they never had any funerals that

amounted to a hill of beans, so I didn't care how

soon they rolled up their big, soulful, blue eyes

and kicked the bucket. They had no meat on

their bones.

But I also met Hans Andersen9 and Robert

10

Louis Stevenson. They seemed to know what I

wanted to hear and said it in a way that tingled

me. Just a little below these friends was Rudyard

11

Kipling in his Jungle Books. I loved his talking

snakes as much as I did the hero.

I came to start reading the Bible through my

mother. She gave me a licking one afternoon for

repeating something I had overheard a neighbor

telling her. She locked me in her room after the

whipping, and the Bible was the only thing in

there for me to read. I happened to open to the

place where David was doing some mighty smiting, and I got interested. David went here and he

went there, and no matter where he went, he

smote 'em hip and thigh. Then he sung songs to

his harp awhile, and went out and smote some

more. Not one time did David stop and preach

about sins and things. All David wanted to know

from God was who to kill and when. He took care

of the other details himself. Never a quiet moment. I liked him a lot. So I read a great deal more

in the Bible, hunting for some more active people

like David. Except for the beautiful language of

Luke and Paul, the New Testament still plays a

poor second to the Old Testament for me. The

12

Jews had a God who laid about Him when they

needed Him. I could see no use waiting till Judgment Day to see a man who was just crying for a

13

good killing, to be told to go and roast. My idea

was to give him a good killing first, and then if he

got roasted later on, so much the better.

9. Hans Andersen: Hans Christian Andersen (18051875), Danish writer known primarily for his fairy tales.

10. Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894): Scottish

writer of adventure stories such as Kidnapped and Treasure Island.

11. Rudyard Kipling ... Books: Kipling (1865-1936)

was an English writer born in India. His jungle Book and

Second jungle Book contain stories of the adventures of

Mowgli, a boy raised by animals in the jungles of India.

12. laid about Him: slang for "struck blows in every

direction."

13. roast: slang for "burn in hell."

WORDS TO OWN

tread (tred) n.: stepping.

profoundly (pro· found'le) adv.: deeply.

resolved (re · zalvd') v.: made a decision; determined.

conceive (kan · sev') v.: think; imagine.

ZORA NEALE HURSTON

757

,. . ,

r-rr!'N

In Search of a Story

'

:I

:

:

In another section of Dust Tracks on a Road,

Zora Neale Hurston tells of her passion, as a

child, for hearing stories from the African

American tradition.

For me, the store porch was the most interesting place that I could think of. I was not allowed to sit around there, naturally. But, I

could and did drag my feet going in and out,

whenever I was sent there for something, to

allow whatever was being said to hang in my

ear. I would hear an occasional scrap of gossip

in what to me was adult double talk, but which

I understood at times ....

But what I really loved to hear was the menfolks holding a "lying" session. That is, straining

against each other in telling folks tales. God,

Devil, Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, Sis Cat, Brer Bear,

Lion, Tiger, Buzzard, and all the wood folk

walked and talked like natural men. The wives

of the storytellers might yell from back yards

for them to come and tote some water, or chop

wood for the cookstove and never get a move

out of the men. The usual rejoinder was, "Oh,

she's got enough to go on. No matter how

much wood you chop, a woman will burn it all

up to get a meal. If she got a couple of pieces,

she will make it do. If you chop up a whole

bo:xful, she will burn every stick of it. Pay her

no mind." So the storytelling would go right on.

...

'I This passion for listening to stories from the

' oral tradition led Hurston to collect folklore

as a field researcher. In this section of her autobiography, Hurston tells of studying anthropology at Barnard College in New York City

and of how she went out among African

Americans to gather their folk tales. In her

first attempts as a folklore collector, she did

not succeed. She had to learn the hard way

that a folklorist must use just the right approach with his or her sources.

758 THE MODERNS

Mecklenburg Evening ( 1984) by Romare Bearden.

Collage and watercolor on board.

© Romare Bearden Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking

and prying with a purpose. It is a seeking that

he who wishes may know the cosmic secrets

of the world and they that dwell therein. . . .

My first six months were disappointing. I

found out later that it was not because I had no

talents for research, but because I did not have

the right approach. The glamour of Barnard

College was still upon me. I dwelt in marble

halls. I knew where the material was all right.

But, I went about asking, in carefully accented

Barnardese, "Pardon me, but do you know any

folk tales or folk songs?" The men and women

who had whole treasuries of material just seeping through their pores looked at me and

shook their heads. No, they had never heard of

anything like that around there. Maybe it was

over in the next county. Why didn't I try over

there? I did, and got the selfsame answer. Oh, I

got a few little items. But compared with what

I did later, not enough to make a flea a waltzing jacket.

-Zora Neale Hurston

MAKING MEANINGS

Building Your Portfolio

First Thoughts

I. Did you identify with

Hurston's love

of books?

What were

your feelings

about books

when you

were younger?

Have your feelings changed?

Reading Check

a. Why is Hurston's

grandmother afraid

of Zora's boldness?

b. Why do white

Northerners visit the

school?

c. What do the two

young ladies send

I

from Minnesota?

'

d. What are the narrator's favorite books?

Shaping

Interpretations

2. Consulting the notes you took while

3.

4.

5.

6.

CHOICES:

~

reading, characterize the narrator. ~

Find examples from the text to support your

view of Hurston.

What qualities does the young Hurston exhibit

when she reads aloud in class?

What does Hurston think about the two women

who visit? How do you know?

Why do you think the visitors invite Hurston to

their hotel?

Why does the young Hurston treasure the

books the ladies from Minnesota send her?

Challenging the Text

7. Hurston was criticized by some of her contemporaries because they felt she did not place

enough emphasis on the racial oppression of

African Americans by the white community.

Using references from this autobiographical excerpt, explain whether you agree or disagree

with this criticism.

Writer's Notebook

1. Collecting Ideas

for an Interpretive Essay

~OHI!tf

~~

~·

The title of an autobiography

can tell you a great deal about how a writer

views his or her life. Write down your reactions to the title Dust Tracks on a Road. Based

on what you learned about Hurston in the biography on page 750 and in this excerpt, why

do you think she chose this title? What does

it reveal about her life experiences? Keep

your notes for possible use in the Writer's

Workshop on page 804.

Comparing Autobiographies

2. Real-Life Stories

In a brief essay, compare this passage from

Hurston's autobiography with the selection

from Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography (page

86). You might compare (a) the narrators'

actions and motives; (b) the narrators' relationships with other people; (c) the incidents

described and why the narrators might have

chosen to write about them.

Creative Writing I Performance

3. Dust Tracks Onstage

Autobiographies are often successfully

adapted and dramatized for the stage. Working with a group, prepare this excerpt from

Dust Tracks on a Road for performance. You

will have to assign scriptwriters, a director,

actors, costume designers, and set designers.

You might also need a narrator to tell the

parts of the story that are not told directly in

dialogue. Consider using music (such as

orchestral, rock, folk, blues, jazz, or rap) to

emphasize important moments.

ZORA NEALE HURSTON

759

Portrait of

Langston

Hughes by

Winold

Reiss.

lc-""

--~

""""- _ . --4::..__.- ·~

-· -

~-

./

..LJ

I

National

Portrait Gallery,

Washington,

D.C., U.S.A

Langston Hughes

(1902-1967)

0

ne evening toward the end of 1925, the

poet Vachel Lindsay was eating dinner in

the Wardman Park Hotel in Washington, D.C.

The busboy, a twenty-three-year-old African

American, left three poems near Lindsay's plate.

Lindsay was so impressed by the poems that he

presented them in his reading that night, telling

the audience that he had discovered a true

poet-a young black man who was working as a

busboy in the hotel restaurant. Over the next

few days, articles about the "busboy poet" appeared in newspapers up and down the East

Coast.

The busboy, Langston Hughes, was no beginning writer. In fact, when he shyly approached

Lindsay, Hughes's first book of poetry, The Weary

Blues, was about to be published by a prestigious

New York company, and individual poems had

appeared in numerous places. Lindsay warned

the young poet about literary "!ionizers" who

might exploit him for their own purpose: "Hide

and write and study and think. I know what factions do. Beware of them. I know what Iionizers

do. Beware of them:· In response to Lindsay,

Hughes wrote back: "If anything is important, it is

my poetry, not me. I do not want folks to know

me, but if they know and like some of my poems

I am glad. Perhaps the mission of an artist is to

interpret beauty to the people-the beauty

within themselves. That is what I want to do, if I

consciously want to do anything with poetry:•

Before this encounter, Hughes had attended

Columbia University and worked his way to

Africa and back as a crew member on an ocean

freighter. Ambitious and energetic, Hughes had

learned early to rely on himself. He spoke German and Spanish; he had lived in Mexico, France,

and Italy. In the years that followed his "overnight" celebrity, he earned his degree at Lincoln

University, wrote fifteen volumes of poetry, six

novels, three books of short stories, eleven

plays, and a variety of nonfiction works.

Born in Joplin, Missouri, Hughes spent most

of his childhood in Lawrence, Kansas, with his

grandmother. When he was thirteen, she died,

and he moved to Lincoln, Illinois, and then to

Cleveland, Ohio, to live with his mother and

stepfather.

Hughes began writing poems in the eighth

grade, and he began publishing his work as a

high school student in his school literary magazine. He read voraciously and greatly admired

the work of Edgar Lee Masters, Vachel Lindsay,

Amy Lowell, Carl Sandburg, and Walt Whitman.

The most important influences on Hughes's

poetry were Walt Whitman and Carl Sandburg.

Both poets broke from traditional poetic forms

and used free verse to express the humanity of

all people regardless of their age, gender, race,

and class. Encouraged by the examples of Whitman and Sandburg, Hughes celebrated the experiences of African Americans, often using jazz

rhythms and the repetitive structure of the

blues in his poems. Toward the end of his life,

he wrote poems specifically for jazz accompaniment. He was also responsible for the founding

of several black theater companies, and he

wrote and translated a number of dramatic

works. His work, he said, was an attempt to

"explain and illuminate the Negro condition in

America." It succeeded in doing that with both

vigor and compassion.

go.hrw.com

7 60

THE MODERNS

LEOll-15

Before You Read

THE WEARY BLUES

Make the Connection

Sweet Blues

Among the great contributions

of American culture to the world

is the music produced by African

Americans: orchestral, blues,

ragtime, jazz, rap, and new musical expressions that you can hear

every day.

The kind of music known as

the blues started to attract attention at the turn of the century, eventually becoming widely

popular in the United States and

abroad and making stars out of

such blues singers as Bessie

Smith and Ethel Waters. In this

poem, Hughes tries both toreport the experience of a "sad

raggy tune" and to capture some

of its rhythms in words.

Quickwrite

•

Blues music has influ~'

enced all kinds of popular music, from rock and soul to

country, folk, and jazz. Jot down

any associations you have with

the word blues. What do you already know about blues music? Is

there any blues influence in the

kinds of music you like?

Elements of Literature

Rhythm

Rhythm in poetry is the rise

and fall of the voice, produced by

the alternation of stressed and

unstressed syllables. Langston

Hughes uses several different

kinds of rhythms in "The Weary

Blues." As he says in the first line,

he uses the "syncopated tune" of

a piano. He also uses the rhythm

of everyday speech, the soulful

rhythm of the blues, and even

the formal meter of traditional

poetry. His poems are true

originals.

Background

On a March night in 1922,

Langston Hughes sat in a small

Harlem cabaret and wrote "The

Weary Blues." In this poem,

Hughes incorporated the many

elements of his life-the music of

Southern black speech, the lyrics

of the first blues he ever heard,

and conventional poetic forms he

learned in school. While the

body of the poem took shape

quickly, it took the poet two

years to get the ending right: "I

could not achieve an ending I

liked, although I worked and

worked on it:' When he at last

completed the poem, "The

Weary Blues" marked the beginning of his literary career.

The Weary Blues

Langston Hughes

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune,o

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenueo the other night

5 By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway .. .

He did a lazy sway .. .

To the tune o ' those Weary Blues.

With his ebony hands on each ivory key

10 He made that poor piano moan with melody.

0 Blues!

Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool

He played that sad raggy tune like a musical fool.

Sweet Blues!

1. syncopated tune: melody in which accents are placed

on normally unaccented beats.

4. Lenox Avenue: street in Harlem.

lANGSTON HUGHES

761

z

~

~

~:

:I

3:

~

C1>

c

3

sa.

)>

~

z

~

o;:J

~:

?

@()

;gO

0 :I

3 ~

~

a.

n> n

o;:J~

.

C1>

"'

"TI

:I

5..

g.~"Till>

0

-o

c c

:I .,

a.n

"':::r

g· ~

--n

C:c

n

C1>

:I

:I

Q.

·

"'

C1> -o

:::r

a.o

CTrt

'< 0

<CT

)>'<

C)!""

.)z>:;·

~

Cl>OQ

~ o;:J

-<o

0 3

.,7':"rt

"'

• PI

Z::~

:-<?

Out Chorus by Romare Bearden. Silkscreen ( 12 lfa" x l61f2").

15 Coming from a black man's soul.

0 Blues!

In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone

I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan"Ain't got nobody in all this world,

20

Ain't got nobody but rna salf.

I's gwine to quit rna frownin'

And put rna troubles on the shelf."

Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.

He played a few chords then he sang some more25

"I got the Weary Blues

And I can't be satisfied.

Got the Weary Blues

And can't be satisfied! ain't happy no mo'

30

And I wish that I had died."

And far into the night he crooned that tune.

The stars went out and so did the moon.

The singer stopped playing and went to bed

While the Weary Blues echoed through his head.

35 He slept like a rock or a man that's dead.

762

THE MODERNS

Birth of the Blues

When asked about the origins of the blues, a veteran New Orleans fiddler once said: "The blues? Ain't no first blues! The blues always been."

The first form of blues, country blues, developed in several parts of the

United States, most notably the Mississippi Delta, around 1900. Country blues tunes were typically sung by men- usually sharecroppers.

The subject was often the relationship between men and women. As

the contemporary blues singer B. B. King once said, the blues is about

a man losing his woman.

From the start, blues music was improvisational- it changed with

every singer and performance. Parts of lyrics were freely borrowed

from other songs or based on folk songs or figures of speech. Lines

might be repeated two or three times, with different accents and

emphases, then answered or completed by a rhyming line:

Black cat on my doorstep, black cat on my window sill. (repeat)

If some black cat don't cross me, some other black cat will.

- Ma Rainey

The blues catch on. The earliest blues singers, among them

Charley Patton, Robert Johnson, and Blind Lemon Jefferson,

played at country stores, at Friday- and Saturday-night dances, at

cafes, and at picnics. The first popular blues recordings, made

in the 1920s, featured female singers such as Ma Rainey and Bessie

Smith backed by a piano or a jazz band.

When rural Southern African Americans migrated after World

War I to cities like Chicago, New York, Detroit, St. Louis, and

Memphis, the blues sound evolved further. Musicians sang about

their experiences in the city, adding the electric guitar, amplified

harmonica, bass, and drums to blues ensembles. Musicians such as

Sunnyland Slim, T-Bone Walker, and Memphis Minnie pioneered the

urban blues sound in the 1930s and 1940s; the next generat ion included the

blues greats Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, and B. B. King. Since then, blues

music has influenced virtually every genre of music, including folk, country

and western, and- most profoundly- rock. Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, the

Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, and Bonnie Raitt have all borrowed freely from