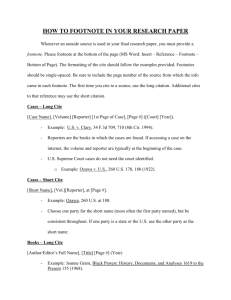

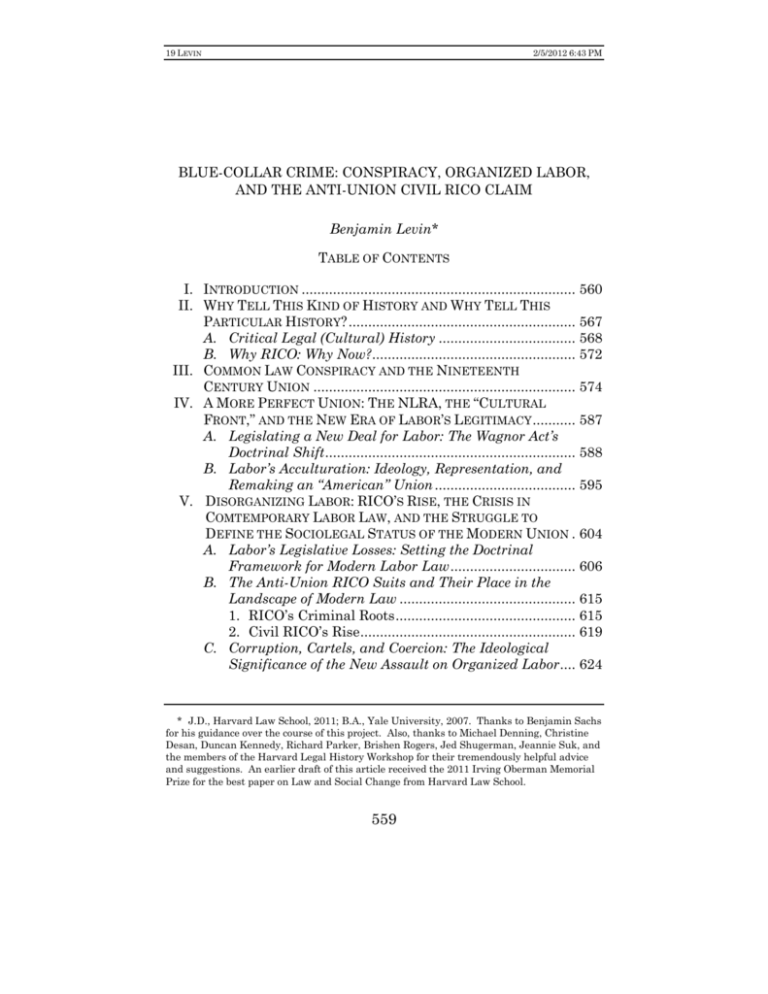

Full Article - Albany Law Review

advertisement