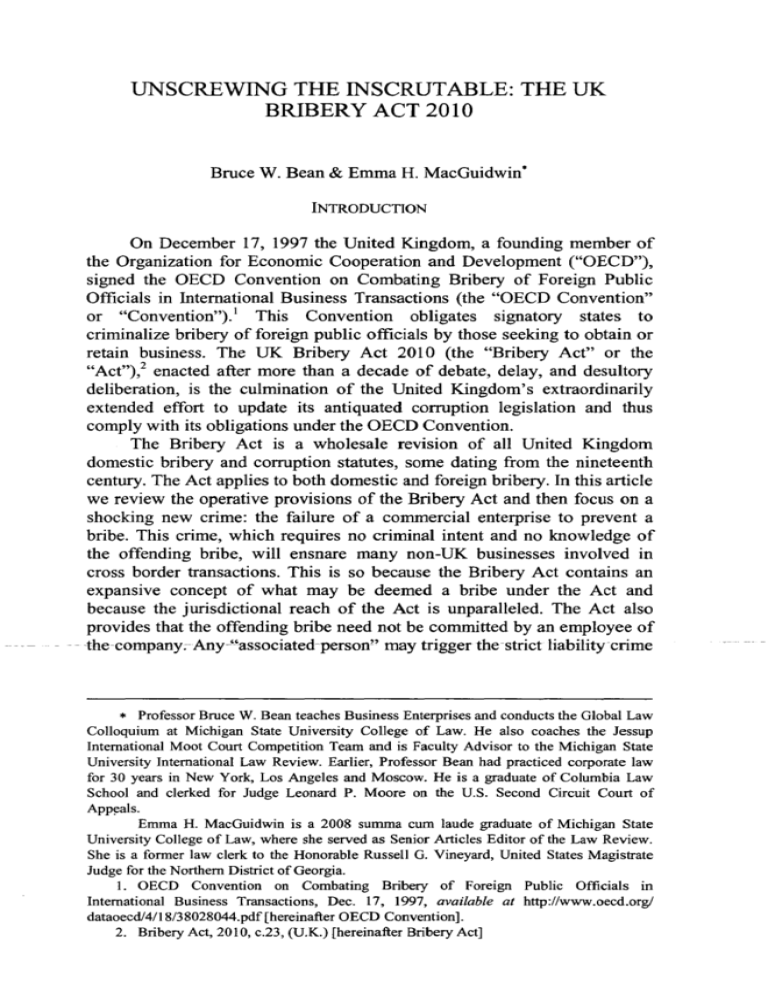

Unscrewing the Inscrutable: The UK Bribery Act 2010

advertisement