4. Citizen Kane

advertisement

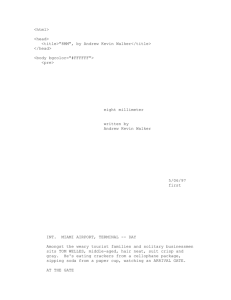

4. Citizen Kane Written by Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles About the writing of the film: • • • • • • • • • • For decades, there has been controversy over what each of the two writers contributed to the film. Both Welles and Mankiewicz had long tinkered with biographical stories that approached the subject’s life from a variety of angles. —multiple sources In his school days, Orson Welles wrote an unproduced play called Marching Song, the exploration of a public figure through the testimonies of the people in his life. —IMDB Welles drew from his personal life for the script, and Mankiewicz drew from publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst’s life, to flesh out the character of Charles Foster Kane. It was long rumored that what enraged Hearst most was the use of the word “Rosebud,” which some have claimed was Hearst’s nickname for his mistress Marion Davies’ private parts. —multiple sources Mankiewicz wrote the first draft of the screenplay in about six weeks, and wrote much of his work from a hospital bed. —IMDB Budd Schulberg on Mankiewicz: “Mankiewicz claimed credit for the concept, and in truth had talked to my father, the producer B. P. Schulberg, about doing a film on William Randolph Hearst before Welles's dramatic arrival in Hollywood.” —The New York Times, “The Kane Mutiny,” 5/1/2005 Schulberg: “Welles rewrote scenes to define Kane as less a monster than a many-faceted public relations genius, as creative as he is finally self-destructive.” —The New York Times, “The Kane Mutiny,” 5/1/2005 Welles claimed that William Randolph Hearst was not the only inspiration for Kane. Among others, Chicago financier Harold Fowler McCormick was also a model for the character, in particular his promotion of his mistress and second wife, Polish opera singer Ganna Walska, who was considered a dreadful singer, despite the thousands of dollars McCormick paid out for her musical training. Another model was Samuel Insull, a Chicago utilities magnate and one of the founders of General Electric, who built what is now the Lyric Opera of Chicago for his singer/mistress. Howard Hughes was reported to be yet another model for the character, as was Time magazine founder Henry Luce. —multiple sources Hearst, who had strong connections to the movie business, heard that he was the (or one of the) subject(s) of the film before it was completed, and tried to have the film suppressed and destroyed. It was rumored that he got access to an early draft of the script because Mankiewicz gave a copy to Charles Lederer (#31, His Girl Friday), the nephew of Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies. Frank Mankiewicz (son of Herman): “Lederer was a friend of Father's, but he was, in addition—which my father knew very well—Marion Davies' nephew, and my father gave him a copy of the script. Now, you want to talk self-destructive, I suppose that's a pretty good example. Lederer says he never showed the script to Hearst, but when it came back to my father, it was annotated, clearly by the Hearst lawyers, and I think that's probably how the old man learned that Citizen Kane was about him.” —The Battle Over Citizen Kane (PBS) When released, Citizen Kane was critically acclaimed but a box office failure, in part because Hearst allowed no mention of it in his newspapers, which made up the biggest newspaper chain in the country. —The Battle Over Citizen Kane (PBS) On the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress About the writers: • Orson Welles came to Hollywood in 1939, shortly after winning national notoriety at 23 for his audacious War of the Worlds radio broadcast, so realistic it scared the wits out of the audience and caused thousands to flee their homes. The script for War of the Worlds was written by Howard Koch, who later co-wrote Casablanca (#1). • • • • • • • • • • By the time he came to Hollywood, Welles had gained also fame for several Broadway productions, including the critically acclaimed “Voodoo MacBeth.” Welles was 24 when he co-wrote Citizen Kane. “There but for the grace of God, goes God.” —Herman Mankiewicz on Orson Welles, brainyquote.com (& multiple sources) Screenwriting awards/nominations for Welles: Academy Award win for Citizen Kane. Herman Mankiewicz was the older brother of Joseph Mankiewicz (#5—All About Eve). Before coming to Hollywood in 1926, Mankiewicz was the drama editor for The New Yorker. Mankiewicz: “In a movie… [the] villain can lay anybody he wants, have as much fun as he wants cheating, stealing, getting rich, and whipping servants. But you have to shoot him in the end.” — bartleby.com (& multiple sources) Mankiewicz was a member of the famous Algonquin Round Table. Fellow Algonquin member Alexander Woolcott called Mankiewicz “the funniest man in New York.” —multiple sources Worked for the Red Cross press service in WWI; later became a foreign correspondent. Screenwriting awards/nominations for Mankiewicz: 2 Academy Award nominations, with 1 win for Citizen Kane.