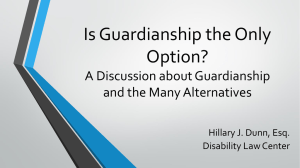

Chapter 7 Capacity and incapacity

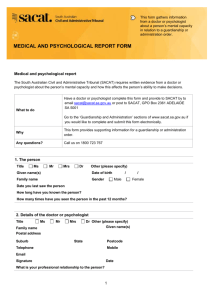

advertisement