From House to Home - Community Services

From House to Home

Housing, Tenancy and Support for People with Complex

Needs Related to their Disability

November 2010

(Updated)

Introduction

Approximately 14.2% of the ACT population (or 45,200 people) identify as having a disability. Of these 3.85% (or 13,000 people) identify as having a profound or severe disability requiring assistance.

The target population for access to disability services in the ACT is 11,702 people with a disability aged between 0-65. Currently, the ACT reaches 31.4% of this target population, excluding employment services. This is higher than the national average of

23.3%.

Within the population of people in the ACT using formal services to support their disability related needs:

24.2% have an intellectual disability,

12.6% have a physical disability,

4.8% have a neurological condition or acquired brain injury; and

22% have a disability related to sensory limitations.

In the ACT 95.6% of people with a disability who currently access supported accommodation services assistance in the activities of daily living. The ACT statistic is the highest nationally, compared to the national average, which is 86.7%

The potential demand for specific housing responses has been estimated from administrative data held by Housing ACT and Disability ACT, ACT demographic data and information from the Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers undertaken by the Australian

Bureau of Statistics. The forecast does not include people who have the financial capacity to modify their own home, and/ or build or purchase a property themselves.

Based on the current service usage in the ACT, the combination of the ageing carer population and client base within the disability it is predicted that an additional 15-20 people will require formal disability supported accommodation services each year.

Based on current data it is predicted that a high percentage of people with disability will live in their own homes; many others will live in the home of their family and/or carer; and the number of people will require access to public and community-based housing.

When writing individual future plans, it will be needed to be acknowledged that natural supports change, and individual‟s accommodation needs are likely change which may lead the consideration of a more formal support option in the future. For information regarding future planning access the future planning guide on www.dhcs.act.gov.au/disability_act .

This report includes a range of housing and property designs and tenancy and support arrangements for people who require sustained formal and informal assistance over their lifetime. It explores supported accommodation models that provide for a range of lifestyle preferences and maximise the ability of the whole community to be welcoming and inclusive of citizens with a disability.

The options explored in this report are intended to reflect the ACT community ‟s needs and preferences. However, the options are tailored to meet the particular needs of people who have complexity/ties related to their disability and consequently will most likely need

1

to share their cost-of-living, and housing, tenancy and support arrangements with other people. These models include:

Independent living – a person living in their own home, with their family or by themselves,

Dispersed housing a spread of properties throughout the community with the goal of properties being indistinguishable in the neighbourhood,

Duplex, dual occupancy and triple occupancies – these are alternatives to larger shared living arrangements,

Intentional communities - a housing model that brings together a group of people with similar philosophies and preferences; and

Cluster housing a number of houses on one site, which are generally exclusively for people with disabilities.

The research targets those property designs that maximise individual opportunity for personal choice and quality of life; and minimise segregation from natural supports and the necessity for highly regularised lifestyles. These designs include:

Standard shared living arrangements - people living in a house sharing the living, kitchen and bathroom facilities,

Split housing with shared facilities - people live in one property with separate living areas and bathrooms, and share the kitchen and laundry,

Joined housing people living in one property with separate living areas, bathrooms, kitchens and laundries. The split house may be joined by a shared office or sleepover room for support workers,

Unit housing under a single roof a series of independent or semi-independent units surrounding a communal living and kitchen area; and

Unit housing hub - a series of small units under multiple roof lines surrounding an office or sleepover building.

While maximising diversity of choice is a strong driver in providing housing, tenancy and support options for people with disability it is limited by the available resources. For most people in the community „resources‟ means personal income, skills and external supports. For a person with disability it may also include the availability of government funding, concessions, services and grants.

In the ACT, it is intended that formal supports funded by the Government are allocated to best support needs of the person, with consideration of the total resources available and within the eligibility criteria defined by Agreements between the ACT Government and the

Australian Government. These Agreements do not include the expectation that all the needs related to a person‟s disability will be met. They do contain the expectation that

Government will make the best use of all available resources and determine priorities in a fair and equitable way.

2

Project Methodology

Objectives

The project objectives include:

1. Anticipation of likely future housing, tenancy and support requirements of people with complex needs related to their disability,

2. Investigation of best practice housing, tenancy and support options for people with complex needs related to their disability; and

3. Development of a range of specific housing designs, tenancy and support options suited to the ACT.

While the housing, tenancy and support options explored in this report have been prepared with a person with a disability in mind, some of the options are generic and therefore are relevant to the broader housing and tenancy market.

Governance and Oversight

The project strategic oversight was provided by a Steering Committee that included representatives from the Department of Disability, Housing and Community Services

(DHCS), community agencies and National Disability Services ACT.

Project Sponsor

Project Owner

Steering Committee

Subject Matter

Experts

Project Manager Working Group

Project governance

The Project Manager was supported by an internal working group of representatives from

Housing ACT, Therapy ACT and Disability ACT. The working group advised the Project

Manager on practical and administrative issues related to the supported accommodation options being investigated.

3

Methodology

The three stages of the project include:

Stage 1 - Research and Assessment

The research and assessment stage included investigating existing accommodation and support models in the ACT, nationally and internationally. It included visits to government and community organisations in the ACT and Victoria, and to people and their families supported by ACT community services. It also included visiting various organisations and people‟s homes, with their consent, were visited to identify the features of both effective and inefficient home design.

Many people were visited, interviewed and attended discussion groups and consultations.

A number of experts on supported accommodation for people with disability were also consulted. These included people with complex needs, their families and carers; occupational therapists; professionals with significant experience in housing design and construction and accessible housing; and people involved in tenancy management.

Stage 2 - Analysis of Future Demand

An analysis of future demand was reviewed from the current profile of people with complex needs who will require a sustained housing, tenancy and support response into the future. This information was drawn from current known demand, including the

Disability ACT Registration of Interest, an assessment of applications to previous funding rounds; and projections of known factors that influence demand like the ageing population and the acquisition rates for degenerative, neurological conditions and acquired brain injuries.

Stage 3 – Development of Recommendations

These are contained in the last section of the report, conclusions, actions and opportunities.

Context

A number of key policies and initiatives provided the context for the project.

(a) ACT Government‟s Social Plan

The Plan includes seven priority areas:

Economic opportunity for all Canberrans,

Respect, diversity and human rights,

A safe, strong and cohesive community,

Improve health and well being,

Lead Australian in education, training and lifelong learning,

Housing for a future Canberra; and

Respect and protect the environment.

4

These priorities have guided ACT Government decision-making and action since 2004 and there have been many achievements in these areas. Progress Reports are released every two years to provide an update on ACT Government achievements and progress against the 2004 Canberra Social Plan actions and targets.

(b) Affordable Housing Action Plan

The Affordable Housing Action Plan was released in 2007 and contributed to increased building activity in the ACT. The Plan included the release of more than 550 residential blocks at West Macgregor and up to 700 blocks at Casey during 2007. The land releases contributed to the stock of housing, in both the sale and rental markets, increasing over time to make housing more affordable for more Canberrans. The Affordable Housing

Strategy can be found at: http://www.actaffordablehousing.com.au/ .

(c) The Department of Disability, Housing and Community Services Service Delivery

Platform

The DHCS Service Delivery Platform provides DHCS clients and community partners with an understanding of the context in which the agency works. It details the platform from which DHCS services are delivered, including the values that underpin these services, the policies and legislation that focus our efforts and themes that run through every aspect of the Department's work. This platform has been built through discussions with DHCS clients, staff, community partners and Ministers.

(d) Challenge 2014 – A Ten Year Vision for Disability in the ACT

The ACT community‟s vision is that all people with disabilities achieve what they want to achieve, live how they choose to live, and are valued as full and equal members of the

ACT community. Challenge 2014 also states that by 2014, adults with a disability should be able to:

be recognised as adults first with similar needs to other adults,

fulfil their need to develop or maintain intimate relationships and to enjoy loving relationships with partners and family if they wish to do so,

have a place they can call home; and

have access a variety of options for affordable and high standard housing.

(e) Future Directions – Towards Challenge 2014

Future Directions: Towards Challenge 2014 is the ACT Government policy framework which aims to improve outcomes and opportunities for Canberrans who have a disability.

It has six strategic priorities:

I want the right support, right time, right place.

I want to contribute to the community.

I want to socialise and engage in the community.

I want to know what I need to know.

I want to tell my story once.

I want a quality service system.

5

This project has a specific focus on Strategic Priority 1 and its objective – ‘I know the range of accommodation options available to me to assist me in my planning ‟; and

Strategic Priority 6 objective –‘I want a service system that responds to my needs and the needs of my family ’.

Responding to complex needs

There are a small number of people who, because of the complexity of their needs, require a specific and individualised approach to their housing, tenancy and/or day-to-day support needs. These complexities may present as:

limitations of mobility;

limitations to cognitive functioning and/or a combination of these,

multiple and complex behavioural problems; and/or

behaviours that place the individual at significant risk of causing harm to themselves or others.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) defines supported accommodation as a service response that includes providing accommodation to people with a disability and services that provide support to enable the person to remain in their existing accommodation, or to move to more suitable or appropriate accommodation. When accessing supported accommodation, people with high and complex needs require a multiple agency service response. Currently, the primary approach to housing, tenancy and support is generally categorised by governments as supported accommodation, which does not meet the needs of many people whose circumstances and support requirements are complex. The ability of a person in this situation to obtain suitable and sustainable accommodation may be inhibited by:

having high physical needs requiring constant support to sustain their lifestyle (for example being dependant on technology to assist in life and/or communication, equipment and support to move, eat and/or socialise); and/or,

as a result of their disability, they may have complex behaviour patterns that could result in harm to themselves or others; and/or

social/emotional/environmental factors impacting on them or their immediate family that reduce their emotional, financial capacity or resilience.

Support principles

Overwhelmingly the research shows that the most significant factor that impacts on the quality of life for people who receive accommodation support is the skills, aptitude and approach of the support team. The foundation principles to appropriately and effectively support people with high and complex needs are briefly outlined below.

(a) Social Role Valorisation

Social Role Valorisation (SRV) is a concept for transacting human relationships and human services formulated in 1983 by Wolf Wolfensberger PhD as the successor to his earlier formulation of the principle of normalisation. SRV is defined as „The application of what science can tell us about the enablement, establishment, enhancement, maintenance, and/or defenc e of valued social roles for people‟.

6

The major goal of SRV is to create or support socially valued roles for all people in society. It works from the basis that, if a person holds valued social roles, that person is highly likely to receive the good things in life that are available to that society. SRV is not a support model in itself, but a way of considering how to increase the social inclusion of people who are devalued.

(b) Person-Centred Planning

Person-centred planning means the person is at the centre. It is based on the principles of rights, independence and choice and creates opportunities for the person to make more informed choices about how they live their life.

Person-centred planning also means that family members and friends are treated as full partners. It recognises that family and friends (natural supports) of people with a disability play a critical role in their quality of life, and provides an avenue for people to be involved in the broader community.

Using a person-centred planning approach creates an environment that allows the service provider to learn what is important for the individual and to act on that basis. It means that planning is done with people, rather than for them and balances the power of the relationship between the individual and formal service provider.

(c) Active Support

Active Support itself is a process that aims to:

make s ure that a person‟s day is full,

increase the time people spend doing something purposeful,

ensure that those people who require more support receive it; and

ensure that people receive support in the form best suited to them.

Active Support is a model of service delivery that focuses on the engagement of people in an activity and the delegation of support workers to achieve this. It values participation and involvement in activities. An important contribution of active support comes from the fact that those who are providing the support are asked to think about individual people as more than receivers of care. Active Support challenges supporters to consider each person as an individual with preferences, likes and dislikes, rather than as a client who needs support.

(d) Positive Behaviour Support

Positive Behaviour Support is a systemic approach to understanding what maintains a person‟s socially inappropriate behaviour. These behaviours are often difficult to change as they serve a purpose for the person and the behaviours are often supported and reinforced by their environment.

Positive Behaviour Support includes an assessment of the person that clearly describes the behaviour; the circumstances that may predict when the behaviour may or may not occur; and identifies consequences that maintain the behaviour. The positive behaviour support process involves goal identification, information gathering, hypothesis development, support plan design, implementation and monitoring. The overarching goal is not to stop the behaviour per se, but to create a positive environment for the person and to provide them with the skills needed to achieve their goals without needing to resort to using the behaviour of concern.

7

The concept of home

At the very core of providing effective and sustainable accommodation is ensuring that it is a 'home'. A home, rather than a house, residential facility, or accommodation, is a key foundation in life that helps sustain and uphold much that is personal, private and intimate about ourselves and reflects our deep identity, values and preferences.

The significance of a home is highly individual, although there are universal indicators that contribute to a sense of home.

Contributors to a sense of home:

Suitable physical environment.

Positive social relationships.

Positive atmosphere engendering feelings of warmth and care.

Personal privacy and freedom.

Opportunities for self-expression and development.

Sense of security.

Sense of continuity.

Contributors to environments not considered to be homes :

Lack of personal freedom and privacy.

Dissatisfaction with the internal social relationships.

Poor physical environments.

Negative atmosphere within the home.

Lack of permanence.

Lack of security.

Lack of ownership.

Most of the indicators of „homeliness‟ relate to the social structure and environment within the house, rather than the physical nature of the house itself.

A recent review of the homeliness of group living in Melbourne found similar indicators that make a home. The review was based on houses built for residents of Kew Cottages, a program of de-institutionalisation undertaken in Victoria. The review indicates the particular importance of people having input into the physical features of the property, like the pictures on walls and the furniture; and the social aspects of the property including the choice of what to do and having control over visitors and occasional group activities.

It also found that the use of generic design and layout lessens the homeliness of a house.

It is not surprising, particularly when considering shared living arrangements, that the culture of the house becomes more important than the physical house itself. However, when a property is designed inappropriately, or when the structure limits the movement of the people, it can have a negative effect on the person‟s quality of life. The living environment for people with high and complex needs can be improved or limited significantly by the house around them.

The primary consideration for accommodation provided for people with complex needs should be that it is the person's home. In most instances the service provider's needs will be a secondary consideration and in conflict situations the best interest of the person should always be primary focus.

Researchers have developed the following set of principles to be followed by agencies providing a supported accommodation service:

8

People should have sovereignty in regards to their homes and lives. All people have the right to be in control over what happens in their home,

Agencies should idealise what is a real 'home' and be guided by this in supported accommodation. An agency should be able to articulate what a home is for the person it supports and the support structures should fit around this, rather than the person fitting with the service,

Designing, establishing and sustaining a home of one's own should be done by the person whose home it is. A person who has input into the design and development of their own home is much more likely to feel ownership over the house and feel connected to its homeliness; and

Whenever a vulnerable person requires safeguarding or supervision, the outcome should be accomplished without subordinating or weakening the person's sovereignty in their home and life. Alternative ways of designing a home to reduce the necessity of restrictive practices can be achieved when building a property and should be attempted wherever possible.

Furthermore, agencies should:

R ecognise that a person‟s home should be principally a private and personal setting, not a public one. It should be obvious that agencies provide support to people in their own home, rather than a person lives in an agency's facility,

Assist the person to personalise their home and lifestyle,

Not own and control people's homes. Wherever possible, the tenancy or ownership of the property should be removed from the service provider. Ideally, the person who lives in the house is the tenant or owner,

Adopt approaches to management that shield people from unhelpful or invasive bureaucracy,

Not compel or coerce people to live together. People should live together because they choose to, not because they have a similar disability or their support funding makes sharing arrangements for the support provider convenient,

Welcome, respect and cooperate with the person's relationships and personal networks,

Use arms length governance mechanisms that enable people to have direct authority over shaping the supports they receive; and

Avoid support arrangements that unduly commercialise relationships with supporters in‟-home sharing arrangements. This applies especially to models where people with disabilities share with people without a disability. Situations where people receive a significant financial benefit by living with someone with a disability can lead to a similar relationship of a support worker to a client, rather than as housemates.

Location is a critical factor in the success of providing quality outcomes for people with high and complex needs. Generally, the following principles should be considered when identifying a potential site for housing:

Flat block: a simple, yet critical, element of the block is that it is flat. Apart from the issue of access, if a person cannot move outside their front or back door without

9

support their independence is unnecessarily limited and their dependence on paid support increased,

Good access to the right community facilities: houses should be situated within a necessary distance of community facilities, including local shops, larger shopping centres, and health and entertainment areas. Caution is needed to avoid potential negative imagery, an example of this includes, providing housing for people with disability in close proximity to aged, health care or correctional facilities. The effect of the visual association of a house for people with disability and a hospital, for example, creates an association that people with disability need to be close to a hospital because they are sick. Invisibility or integration of the house in the suburb is of primary importance,

Immediate access to public transport: a significant number of people with disability particularly those who may experience sight impairment, limited physical mobility, and those who have limited disposable income, are dependent on public transport. A closely located public transport hub allows a person to more naturally link with their community. If a person with limited mobility needs to travel some distance to get transport, they may be more likely to remain at home more often and limit their access to the community; and

Smaller rather than larger: for people who have complex behaviour patterns it may be important to limit the changing dynamics of their environment by them living in smaller settings. Smaller does not necessarily mean only one or two people can live in a house, but the house should be designed to give people an opportunity to have time to themselves when they want to.

Housing, tenancy and support options in the ACT

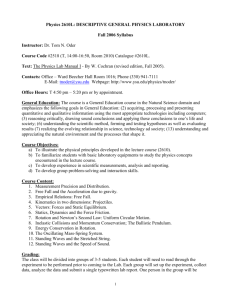

Since 1999, Housing ACT has purpose built 47 properties specifically for people who cannot access housing in its standard form. These properties range from two bedroom units to six bedroom houses. In total those 47 properties housed 88 people.

In 2010-11, Housing ACT will provide over 300 new properties that will meet the principles of universal design. A person who is eligible for public or affordable housing can access a modified property that will suit their needs from Housing ACT or a range of community providers. Additionally, there are a range of properties in the ACT that are accessible for people who use a wheelchair for mobility. These properties have wider doors and hallways, modifications to kitchens and bathrooms so that they can be accessed and, in some cases, strengthened walls and ceilings to accommodate specific equipment.

10

20

15

10

People housed

Properties built

5

0

19

99

-0

0

20

1

00

-0

20

01

-0

2

20

02

-0

3

20

03

-0

4

20

04

-0

5

20

05

-0

6

20

06

-0

7

20

8

07

-0

20

08

-0

9

20

09

-1

0*

Housing ACT – number of properties built and people housed in the period 1999-2010.

Housing

All people have the right to choose to live alone and people with disability should not be forced because of their disability to live in arrangements that don‟t suit them. It is acknowledged, however, that people with disability are less likely to be able to purchase their own house or to enter the private rental market. This is exacerbated when the disability is complicated by complex physical and/or behavioural needs and the person is less likely to access accommodation in its standard form. The individual will require additional financial capacity to purchase and maintain their own home.

Living alone is often only a feasible option for people with complex needs if they have natural or unpaid supports, their own financial resources to purchase additional formal supports, or where there is capacity to share formal supports with other people who are in close proximity.

People with disability, like anyone else, can obtain housing in a variety of different ways:

private rental,

home ownership,

trusts,

public housing; and

community housing.

Supported Living Arrangements

Sustainable and appropriate supported accommodation is a combination of housing, tenancy and day-to-day support with activities of daily living. Until recently these services have varied only so far as to the number of people who share the house, rather than individual preferences or whether sharing is the best option for the person, or their decisions about with whom they may wish to live.

11

(a) Dispersed housing

ACT Government-owned housing is now generally dispersed throughout suburbs without clustering or properties being grouped closely together. These properties may be purpose built or purchased and include units and detached and semi-detached houses.

(b) Close housing

Close housing is a model that intentionally sets a number of properties within close proximity for the purpose of creating opportunities for people to share supports while enabling people to live without full-time formal support in their home. Close housing is often underpinned by, and has the additional benefit of, creating a community amongst the people in the properties.

For people who need a more supported living environment there are a range of accommodation and support alternatives that may fully or partially meet their needs:

Individual Support Packages and support services such as those provided by the ACT

Home and Community Care program, environmental supports, modifications and equipment generally suited to people living in their own tenancy,

Group home arrangements are predominant in the ACT combining formal housing, tenancy and support. The size and configuration of the living arrangement is largely driven by the needs and mix of people living in the house, their family‟s preference and available resources. Many of the houses are standard suburban properties and require minimal or no modifications. The majority are rented from Housing ACT. While some supported accommodation providers historically have delivered both housing tenancy and support as part of their service model, the preferred and best practice approach is a separation of housing and tenancy management from the provision of day-to-day support,

A linked or networked community model (also known as Linc or key ring model) is a model whereby a community organisation provides homes located over a specific geographical region. Tenancy is managed by the organisation and support for day-today living can be provided by a range of agencies but coordinated by one organisation.

People are encouraged to become familiar with, and connected to, their local community and thereby build and maintain a range of natural supports from within their neighbourhood and community that augment their formal supports,

A co-tenancy model where people with disability co-tenant with people without disability, mainly using private rental options. Under negotiated Occupancy

Agreements, the co-tenants without disability lives either rent-free or on a reduced rental in exchange for the provision of some discrete day-to-day personal and/or tenancy support,

A Responsive or Friendly Landlord model (also known as supportive tenancy management) provides a higher level of tenancy support for people who are resident of public or community housing. The additional tenancy support may include budget management, organising utilities, negotiating with flatmates, paying utilities and property maintenance. The responsive tenancy manager does not provide the inhome accommodation support,

Cluster housing where a community organisation owns a number of houses, on one site, that may have multiple uses such as supported accommodation, respite and day activities. The support to each individual is generally highly formalised and regimented, for example shared meals, activities and daily routines; and

12

Further information on how to register for public housing through Housing ACT can be found at http://www.dhcs.act.gov.au/hcs/public_housing or by contacting the Disability

ACT Information Service on 6207 1086.

Design principles

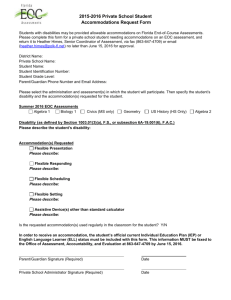

Universal Design Principles

The majority of people with disability in the ACT can have their housing needs addressed through properties that are accessible and based on the principles of universal design.

The principles of universal design, accessible and adaptable design and visitability are all approaches to make houses more accessible to a larger group of people.

The concept of universal design involves the design of products and environments to be useable by all people, without the need of adaptation or specialised design. The principles are:

Equitable use - the design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities,

Flexibility in use - the design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities,

Simple and intuitive use - use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user's experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level,

Perceptible information – the design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user's sensory abilities,

Tolerance for error - the design minimises hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions,

Low physical effort - the design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue; and

Size and space for approach and use - appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of user's body size, posture, or mobility.

Adaptable, Accessible and Visitable

Adaptable housing, accessible housing and visitable design are terms that are used often in discussing housing for people with a disability. The terms are often confused and used interchangeably, but each has a specific meaning and result.

Adaptability is the term used to describe a structure that is capable of being modified, at minimum cost, to suit the changing needs of its occupants. The functions of a house don‟t change, but the lifestyle and the needs of those who spend their private lives there will change over time. Living in an adaptable home that can be modified to suit those needs ensures the occupant will not need to move to more accessible accommodation.

Visitability is a concept that allows for people with a disability to visit someone else‟s house and use the living areas and toilet. It does not generally extend to long term living considerations, only requiring that a person with a disability can access critical parts of the house.

Accessible design is the term used to describe design that complies with certain rules intended to ensure that the design is accessible for most of the population. While many

13

of the Standards apply to commercial and institutional buildings, some also apply to housing. The Standards state precise dimensions and describe the features expected of an accessible design. If a building is determined to comply with the Standards, it is expected that 80% to 90% of people will be able to use that building.

VISITABLE DESIGN

ADAPTABLE DESIGN

ACCESSIBLE DESIGN

Constant support 24 hours per day

Approx 45,200 total population of people with disability

UNMET NEED

IN DESIGN

Approx 13,000

People with a profound or severe disability

400

People accessing formal accommodation support

Approx 100-150

People accessing formal accommodation support who live in a specific, purpose built property

No support required

Targeted cohort of people who require a purpose built property in the ACT

Supported accommodation options and designs

Models

(a) Dual Occupancies

Dual occupancy is the re-development of a block, originally designed for a single dwellin g, to accommodate two houses. The concept has been included in Canberra‟s urban development policies since 1986.

A dual occupancy response for people with complex needs provides an opportunity for a number of people to reside in two houses with the potential to share support. As in the example below, two properties are built close together but remain as separate homes. A dual occupancy arrangement can house the same or more people than a single dwelling, but with greater independence for the occupants.

14

Support provided in a dual occupancy can be quite different to that provided to people in a group home. If the same level of direct support is provided across two houses as would have been provided to one group home, the apparent level of support and most importantly the intrusiveness of the support will decrease. For example, if overnight support is shared across the two houses, people in one house have the security of support at hand without the intrusion of someone sleeping in their house each night.

While the apparent level of support may decrease, the actual level does not. The houses can be joined by a range of electronic devises like intercoms, monitoring systems or medi-call style buttons. The actual system used depends on the individual's capacity and needs as for example, a medi-call system is only useful for someone who has the physical and cognitive capacity to trigger the alarm when necessary. A monitoring system can be intrusive and unnecessary for a person who can indicate that they require assistance.

(b) Triple Occupancy

A triple occupancy is based on the same principle as a dual occupancy, but with three houses on one block. Triple occupancies provide greater opportunities for sharing resources than a dual occupancy.

(c) Intentional Communities

The term 'intentional community' is widely used for a housing project that aims to attract a group of people with a common interest. An intentional community is generally created with a specific purpose in mind; either as a social engineering experiment or to bring together people with shared beliefs or philosophies.

For the purpose of this project, an intentional community is one that focuses on housing response for people with disability including some or only people with complex needs. An intentional community is often confused with cooperative models of housing and tenancy.

There are some risks associated with creating intentional communities for people with complex needs. These risks include the possibility of increasing people‟s vulnerability to poor support or abuse, to people becoming more isolated from the mainstream community; and the creation of parallel, separate and segregated services and facilities.

(d) Co-Housing

15

Co-housing as a model first emerged in Denmark in the 1960s and incorporates unit title home ownership with joint ownership of common areas. It differs from an intentional community model as it does not include pooling resources (for example, food, supplies or clothing).

In a co-housing model, the houses are generally situated around a communal house with shared amenities such as a kitchen, dining room, laundry, guest rooms, home office support, workshops, and arts and crafts. But all privately owned homes are self-sufficient with complete kitchens. Dinners in the common house can occur frequently or occasionally, depending on residents‟ preferences.

A co-housing development is designed by the owners and varies depending on their needs, wants and resources. These communities are democratic and do not support any ideology other than the aspiration to live in a more social and sustainable community.

Co-housing is becoming increasingly popular in the United States with registered cohousing associations across most states in the country.

(e) Co-Operative Housing

Co-operative housing is similar to co-housing, but in a co-operative model the residents generally pay a subsidised rent to a governing body rather than the houses being owned by the individuals. There is also generally less of a focus on communal mealtimes and activities, focussing more on a community itself.

An example of a co-operative model is the Deohaeko Support Network which is based in the Rougemount Intentional Community in Pickering, Ontario Canada. Rougemount is a

105-unit government-housing co-operative where six units are specifically for the use of people with disabilities while the remaining properties are for other community members looking for a good place to live. Although the units are rented by the government, the operation of Rougemount is based on principles of mutual ownership, effort and support.

It is owned equally by the cooperative members. This creates continuity of home life and relationships, and ensures that all members have full rights and valued roles in the running of the cooperative. People with a disability are key residents in the complex.

(f) Cluster Housing

Cluster housing typically involves the support to a number of houses in a residential street, a number of houses at the end of a cul-de-sac, or a group of houses together on one site.

Cluster housing is often a controversial accommodation model. Clusters can range from four to over one hundred properties on a single site and are generally exclusively for use by people with disabilities. Some clusters include on-site day activities and medical facilities.

A recent report from the United Kingdom assessed the quality and cost of outcomes for people in dispersed housing and residential settings. It found that residents of dispersed housing faired significantly better in their quality of care and enjoyed a higher quality of life than those in larger residential settings, including cluster models. It also found that residents in dispersed housing were generally more engaged in the community than those in larger clusters. Similarly, a Canadian study compared the quality and costs of various accommodation models for people with disabilities and found that when cluster housing is compared to group housing it can be associated with:

larger settings,

fewer staff providing support,

16

greater changes and irregularity,

restrictive management practices,

limited activities, sedentary lifestyle,

more restrictive leisure, social and friendship activities,

poorer quality of care,

poorer quality of life; and

a poorer quality of care and a poorer quality of life for individuals.

In 2007 a paper on cluster housing in the Australian context asserted that while cluster housing is an improved option to institutional responses, it carries a number of risks in implementation. The paper assessed cluster housing in context of the physical aspects, grouping implications and activities.

The paper posits that the physical aspects of a cluster development pose a series of potential risks:

the surrounding community often resists a cluster housing development and that exacerbates the community rejection of people with disability,

in an attempt to mitigate the risk of community resistance and reduce the risk to people and because of the quantum of land needed - clusters are often built on isolated sites, further isolating the individuals from the general community,

the subsequent effect becomes a need to transport residents some distance to community facilities and shops which is most effectively provided by a bus service.

These have become known as 'cluster buses', again re-enforcing social exclusion; and

the design of properties in clusters can be different to the surrounding community, as the houses are often designed with protection mind, rather than as a home.

The group image of cluster housing is assessed in relation to grouping a large number of people together. A risk of cluster arrangements is that they can exude a negative image because the majority of the group may already be perceived as less valued by the community. The size of the grouping is also likely to have an effect on the image that, by association, people in the cluster arrangement become known as the 'disabled village people' or similar, and that this continues the social exclusion of people.

The majority of risks and negative outcomes of a cluster model appear to relate to the size and differentiation of the cluster from the surrounding community. However the most significant benefit of the physical cluster model is the sense of internal community created by the nature of the cluster.

The developer of a cluster model must consider the significant risks of disadvantage to the individual. A smaller cluster, or one that is not specifically for people with disability, is less likely to attract the negativity and risks associated with a larger or exclusive cluster.

For example, a complex of 50 houses split between public and private ownership could include 10 -15 houses for people with disability spread throughout the complex. Of those

10 properties, 2 or 3 could be for people with high and complex needs. This would minimise the potential for the risks identified with cluster housing to appear, while retaining the potential for the creation of an internal community within the complex, sharing of support services and potential for inclusion in wider community activities.

17

Group Living

There are countless variations of supported accommodation models, ranging from living alone with occasional drop-in support to full institutional care. In the ACT the most common accommodation response for people with high and complex needs is small to medium sized congregate living arrangements (with 2-6 people) in which the service provider owns or rents the house, provides tenancy support and, as is often the case under historical arrangements, the day-to-day personal care.

The accommodation choice of people with complex needs is often driven by the cost and resources available; the availability of paid and unpaid support, and families‟/guardians‟ need for a safe, secure and sustainable environment for their family member.

In 2001 the Board of Inquiry into Disability Services recommended that the ACT

Government adopt '…a policy of progressively withdrawing from the group home model as the predominant residential support arrangement, moving towards an individualised and integrated care and support model.' The Government noted this recommendation but retained group homes as an option for people with complex needs.

Many group home arrangements congregate people on the basis of their shared characteristics in the belief that this will offer a better quality of care. Evidence suggests that people generally have relatively little input into the choice of the support workers in their home; or with whom they share their home. These decisions are normally made by the service provider. However as described earlier, for a sustainable home the mix of people living together should be based on their own choice.

Generally, a group home arrangement is unable to offer flexibility and is necessarily highly regularised, with the needs of the organisation or its support workers overriding the preferences of the individual. This leads to low levels of personal choice and autonomy about day-to-day routines, activities and decisions.

However, a recent Canadian study did find that individuals living in group or shared arrangements had comparatively favourable outcomes when compared to highly regulated institutional living (with more than six people living together), in particular creating and sustaining social networks with people who are not staff or family.

18

Example of a group home concept.

Challenges

One of the key challenges of a group home arrangement is the risk of creating an environment that is driven by the service or service provider, rather than individual need.

People can become identified by their disability and support need, rather than their individual traits, likes and personality.

Using a person-centred approach, active support models can minimise the risk of institutionalisation within this environment. The best outcome for the person occurs where the power balance between the residents and the agency providing the support is weighed in favour of the individual. Support structures within group living arrangements vary according to the size of the house and the individual resident's needs, but at a generic level the support will be more intensive in the morning, lunchtime and the evening to match the usual times that people need more support.

Living in a group arrangement means that people can generally receive higher levels of support than if they live alone; and have comparatively higher independence than people in an institution setting. However, the support structure can restrict people, as the needs of the group can overrule the needs of the individual.

Feasibility

Group homes are a feasible model of supported accommodation in the ACT. A house where support is provided twenty four hours per day becomes sustainable when there are at least three people sharing the support of one staff member. The table below identifies possible models, house sizes and support provision in a group home for people with high and complex needs.

Accommodation

Model

Cohort Number of residents

Day time support

Overnight support

4 to 6 1.5 - 3 1 Dispersed housing

Dispersed housing

Dual occupancy

Dual occupancy

Triple occupancy

People with high physical needs

People who exhibit challenging behaviours

People with high physical needs

People who exhibit challenging behaviours

People with high physical needs

3 to 4

8-10

6-8

9-13

2 - 2.5

3 - 4

2 - 4

3 - 5

1

1-2

1-2

1.5-2

19

Triple occupancy People who exhibit challenging behaviours

7-10 3 - 5 1.5-2

(The actual composition of a group home and the support provided will be wholly dependent on the people who live there. These figures are indicative only.)

Split Housing

A split house is a different way of designing a group home. The Victorian Department of

Human Services describes a split house as a five or six bedroom house under one roofline, divided into two halves; so that each half can function independently of the other except for the shared facilities (ie. each end has separate living, dining, bedroom and amenities areas). The building includes a common sleepover/office, kitchen and laundry are shared between the two halves of the house. The house also has a common front door.

Bed 1

Living 1

Bath

Bed 2

Laundry

Office

Bed 4

Living 2

Bath

2

Bed 5

Dining 2

Bed 3 kitchen

Dining

1

Entry

Example of split house concept.

Compared to a group home of the same size, this style of housing offers an opportunity for more individual independence and autonomy with less forced interaction with others.

Support structure

The support structure of a split house is similar to a group home, but the support provided during the day will generally be specific to residents in each half of the house, rather than to all of the people as a homogenous group. The overnight support will generally be shared across the entire household.

During the day, the support staff work with people in either end of the house, with interaction occurring as people desire. This support model has a comparative benefit over a group home as the housing design drives a more individualised support structure.

However, the risk of institutionalisation is increased in this model when compared to a group home as there are more people living under one roof and the kitchen and laundry are shared between the two houses. The household could be driven by the demands of service efficiency rather than the individual and consequently there is potential that it will become structured and institutional.

20

Feasibility

Split housing is a feasible concept for the ACT if it is resident driven. A split house that has eight or nine bedrooms is as likely to become as institutional as a group home of that size. To mitigate this, the size of the house should not exceed six or seven bedrooms in total. The table below identifies possible models, house sizes and support provision in a split housing model. A sustainable support structure would be achieved with five people

(two people on one side, three on the other) who share the assistance of three support staff during the day and one person overnight.

Accommodation

Model

Cohort Number of residents

Day time support

Overnight support

Dispersed housing

Dual occupancy

People with high physical needs

People with high physical needs

5 - 6

10 - 12

2 - 2.5

3 - 5

1

1-2

(The actual make up of a split house and the support provided will be wholly dependent on the people who live there. These figures are indicative only.)

Joined House

A joined house is two separate homes under one roof that share an office/sleepover room for support workers. This model affords more privacy, independence and homeliness to the split house model as it separates the two houses physically, each house also functions independently.

This type of accommodation is largely the same as a duplex, with the unique characteristic of the two properties being internally connected. This outcome could be achieved by modifying an existing duplex.

21

bath

Living

Office/ sleepov er

Living

Bed 1

Laundry

Bed 3

Bed 2

Dining

Bed 1

Laundry

Bed 2 bath

Example of a joined house concept.

Support structure

The support structure is likely to be significantly different to a group home or split housing. The physical separation of the house should drive separate support models in each house, but with the potential of shared overnight supports. The central office would become a hub for the support service and electronic communications could be established so people who can spend time without direct support might live in one house, while people who require constant support might live in the other. Supports can be provided flexibility according to different need and preferences and in a cost effective way.

Feasibility

Joined houses could be feasible in the ACT, particularly if using existing properties. A single level duplex, or any properties with a common wall could be modified to create the shared support capacity provided by this model. Alternatively, joined housing could be used as a replacement to larger group homes which are no longer suitable for the people who live there.

Using either of the split housing models in a model larger than a dual occupancy may not be appropriate if the houses are specifically for people with high and complex needs.

The size of the properties and grouping of a large number of people with a disability so closely has the potential to reduce quality of life. It may be possible to use split housing on a larger model if all of the properties are not specifically for people with high and complex needs.

22

Unit Housing

Unit housing is a concept that came up often during the consultation for this project. Unit housing is where people live in a series of bedsits that surround a common living area. It is a popular model in aged care and has been used in the ACT to accommodate single people and young people who need a level of support related to other social or lifestyle factors.

An example of unit housing is where people live in an area with an individual bedroom, bathroom and small living area with a common living and kitchen area in the centre.

Example of unit housing concept showing independent living under one roofline.

In the example above, the yellow shaded units have a kitchenette, allowing those people to live almost entirely independently of other residents if they choose, while the other two people would use, or be supported with their meals from, the communal kitchen.

This model is based on a premise that people with high and complex needs may share accommodation with people needing lower levels of support, or people without disability.

It is a housing option that may suit people with degenerative conditions as the living arran gements are easily adaptable to the individual‟s changing support needs

23

Example of independent living unit concept.

Support Structure

The unit housing model allows for a range of support structures including for a couple to live in a group arrangement. For a variety of reasons, many partners of people with a disability are not able to provide the constant and intensive support needed by their partner. The unit housing provides an opportunity for that support to be available while the individuals are able to maintain their lifestyle privacy and independence.

The support to people in the unit housing model is similar to that of people in a group home of the same size, but it offers comparatively more opportunity for independence and consequently higher quality of life for the individuals. Unit housing is a feasible housing option for people who have challenging behaviours in order that the higher level of support can be drawn upon when required. People have opportunities to socially interact when they want to and safety is maintained at other times. In addition, by virtue of having more personal space for some people, the potential for them to escalate in agitation may be reduced.

Unit housing hub

Another example of unit housing is a number of units on one site surrounding a central

'hub' that includes an office, sleepover and communal living and kitchen facilities. The physical separation of the units does create a model closer to a hostel, or aged care support model. The physical separation of the units risks losing the community feel of the unit house, but for people with challenging behaviour, this model provides some separation from other people when necessary without excluding them from the community as a whole.

24

Example of unit housing under multiple rooflines.

There is a risk with this model that the people needing lower levels of support may be deskilled as there is a higher level of support available. If this occurs the cost of providing support increases as people are over supported and the efficiency in the model is lost.

Support structure

Of the group living models, the unit housing model could require the highest level of support cost, as the residents live essentially independently. Each person would be supported in their own unit, while sharing support across the group. Overnight support would be shared by all residents.

If this model was employed under multiple rooflines it would be enhanced by the inclusion of electronic communications and monitoring systems. Installing these environmental supports allows people to have a higher level of independence while maintaining the necessary level of support. The support staff could be shared between all residents on an on-call basis, rather than direct and constant support. However, this would be based on individual need, rather than a generic approach to the support.

There is risk that the support will become quite regimented and inflexible. While the intent of the built form is to allow independence, the communal facilities in the property can lead to the service, rather than the residents, controlling the home.

Feasibility

This accommodation model is feasible for people with high and complex needs if the support methodology and philosophical approach is person-centred and flexible. Unit housing is a model that can be seen as close to a hostel rather than a home, but through the course of this project a substantial number of people indicated that either of the unit models described could benefit some people.

People with high physical needs could make positive use of either unit housing models, but people who exhibit challenging behaviours may be better suited to the multi-roof

25

model where there is more physical separation between the units and more opportunities for people to have time to themselves when necessary. It is likely that the support needed in the separated unit model would be slightly higher than the one roof model, unless electronic communications were installed to ensure individual safety. The table below identifies possible house models, house sizes and support provision in a unit housing model.

Accommodation

Model

Dispersed

Dual occupancy

Dispersed

Cohort Number of residents

Day time support

Overnight support

1.5-3 1 People with high physical needs

People with high physical needs

People who exhibit challenging behaviours

4-7

8-14

4-6

3-6

2-3

1.5-2

1

(The actual make up of unit housing and the support provided will be wholly dependent on the people who live there. These figures are indicative only)

Shared support structures

Supporting people in their home does not translate automatically to an individual support worker present all the time. In the age of emerging technologies, particularly electronics and internet communications, the future of support may look quite different. The following examples are feasible today, but with more intelligent technologies the support models will become more realistic and achievable. Both of the models below attempt to remove the workplace from a person's home. A challenge for service providers is the balance between the fact that services are generally provided in a person's home, with the necessary administrative work to maintain a support service.

(a) Joined Up Communities

Joined up communities is a concept where a number of people with disability, some with high and complex needs, live in close proximity to each other within a suburb and share paid supports.

Five or six people who need close support overnight, but not necessarily direct support, could have their properties linked by electronic means with access to a single support worker who is on call overnight. The support worker may be based in the house of the person most likely to require support, or in the house most central to the group. The individuals would have access, either through intercom, med-call or mobile technology to indicate to the support worker a need for assistance. During the day the level of support would increase to two-three support workers scheduled throughout the day to support people at various times. The individuals may be able to supplement the paid support with support and assistance from family or others.

26

Example of a joined up community concept

The risks with this model include prioritisation of support when more than one person requires assistance at the same time. While this is a current and constant issue in a group home model, the support staff member can assess directly the priority of need and support the individuals accordingly. In this model there is physical separation making that assessment more difficult. Another risk is system failure. Backup systems and protocols need to be in place in the case of blackout, or loss of connection between the houses, to mitigate the risk to the individuals.

This model could be suitable for people who wish to continue to live in their own home as independently as possible but who do not need to receive constant, direct support.

(b) Back Fence

A back fence model is demonstrated where two, three or four properties border one another. One of the houses may be a purpose-built house for a person with high and complex needs, while the others would be standard houses for people with less complex needs. An office/support unit would be installed between the houses to remove the need to have an office inside anyone‟s home. Clerical and other administration can be undertaken outside the person ‟s home, protecting the feeling of homeliness. The back fence model is one that would be suitable to employ in the unit housing and split housing models.

Conclusions, Actions and Options

The objectives of this project were to:

1. Anticipate the likely future housing, tenancy and support requirements of people with complex needs related to their disability.

2. Investigate best practice housing, tenancy and support options for people with complex needs related to their disability.

3. Develop a range of specific housing designs, tenancy and support options suited to the

ACT.

27

The information gained through this project will assist future property design and provide a basis for discussion for individuals and families thinking about their future accommodation and support needs and opportunities.

The following conclusions, actions and opportunities have been identified and are cast as recommendations to continue the expansion of housing options for people with disability in the ACT. These are linked to the implementation of Future Directions: Towards

Challenge 2014.

Conclusion 1. Currently the housing options available for people with high and complex needs are substantially more limited than those available to other people.

Because people with high and complex needs require a high level of support, their housing options have largely been restricted to the availability of vacancies in group housing. However, as shown through the examples of unit housing and joined up communities, there are models beyond the traditional group home model that can support people to live with independence without sacrificing their wellbeing and safety.

Conclusion 2. Houses governed by the people who live in them are the most successful.

Households that are run by the people who live in the house are generally more successful and sustainable than those run by an external entity. This is also a more natural and normative arrangement.

Ideally, the support service provider should not be involved in the house as an asset - either through ownership or tenancy management. This is not an immediate or short term option in some circumstances; for example where community sector organisations own properties as part of their service. However, approaching accommodation support from the perspective of providing a service to a person in their own home, rather than from the perspective of providing support to people in the agency‟s facility, is critical to assisting people to live the best life possible.

Conclusion 3. A range of accommodation models can be used in the ACT.

For some years we have accepted that people should have access to a range of accommodation models beyond, and more community-focused than, group living. Cotenanting and key ring models have been successfully introduced in the ACT in the last five years.

Looking at alternatives to group homes on a broader scale is the next challenge. Split housing, unit housing, dual occupancies and duplexes provide opportunities for people with high and complex needs to receive higher levels of support than they could achieve living by themselves without the enforced community of group living. Having a variety of options offers choice, while ensuring people‟s supports and services are able to effectively meet their needs.

Conclusion 4. The likelihood of achieving a home is more related to the environment and support structures than the physical form, but the physical form can assist or deflate the likelihood of homeliness.

The use of materials, the layout of the house, the location and styling and other features have a direct impact on how residential or, alternatively, how homely a house will feel.

Equally important is the environment in the house; the support that is provided, the way people are treated, the autonomy and control residents have over their own lives all act to create a sense of home, or in a negative environment, a sense of institutionalisation.

28

Conclusion 5. People who need constant support should have housing options beyond group homes and service agencies and families should consider alternative ways to enable options to be available.

Many service providers already provide person-centred planning and flexible responses.

However, to provide other forms of accommodation to people with high and complex needs, the sector needs to further consider ways of providing support and engaging with people and their families.

Most of the models in this report provide the same opportunity for personal safety and wellbeing, but provide more independence than the group housing model. A direct way of increasing independence is to change the way support is provided. For instance, where a person needs support with self-care, transitioning between chair and toilet etc, a support person does not necessarily need to be in direct contact at all times, but the assistance needs to be accessible. The challenge in implementing models in which people living in different buildings and sharing support services, relates to those people and, in particular, their parents and legal guardians accepting that full time support may not necessarily mean that a worker is directly with them at all times.

Conclusion 6. The use of electronic communications, monitoring systems and environmental control units is an untapped potential.

Support provided through the use of aids and equipment can be effective in the longer term and can enhance the person‟s quality of life. In particular, the use of electronic monitors and environmental control units could be expanded in purpose built houses. An electronic communication device, intercom, med-call or monitoring type device can provide an individual with support and security without the intrusion of a constant direct support person. For example, four people who live in unit housing may share one sleepover support worker who is contactable by intercom. Each of the people has direct access to the worker although they may not be sleeping in the same building.

Action 1: Review the existing housing used by people with high and complex needs across the disability sector.

All disability housing providers in the ACT (both government and community) should review the existing housing stock to assess the continued viability of their properties. A strategic assessment of when the properties are likely to need replacing based on changing client needs and property age and structure, will provide a stable base for planning property needs in the future.

For community agencies which own housing assets, a strategic assessment of the viability of continuing to own the asset could be undertaken in conjunction with consideration of the needs of the individuals already living in the properties. The review should also assess the projected demand for additional specifically designed housing stock.

Action 2: Establish a project to investigate ways the ACT community could provide greater support and flexibility to people who wish to pursue their own housing option.

There are a considerable number of housing options for people with disability beyond a government provided property. An investigation into practical ways to support people who can pursue their own housing options could include an assistance scheme that provides low interest loans to people to modify their own home. For example, the

Queensland Home Adapt Loan Scheme provides loans of between $5,000 and $30,000 at fixed interest for private home owners who have a disability, or who live with someone

29

with a disability, to modify or adapt their home. This scheme has the potential to reduce the number of people who would need to enter publicly supported accommodation in the future, or at least delay their need for that type of service, as families may be able to modify their home and people could continue to live in a family environment while that is a preferred option.

Similarly, opportunities for tenants and community organisations to pursue ownership of properties could be undertaken as a concurrent activity.

Action 3: Consider how to improve the management of capital projects for people with a disability.

Strategic management of capital projects may provide opportunities for housing people with high and complex in a more timely and effective way, enabling the greater use of different housing models. The capital program would be informed by information in a single registration of interest process.

Action 4: Create a single register of people with high and complex needs who require accommodation support in the ACT.

The Disability ACT Registration of Interest is the central register of need for formal supports by people with a disability in the ACT. However, this is not a waiting list.

Community providers generally have their own registration and/or waiting list processes.

A single register of people with high and complex needs who require accommodation support could be used by Housing ACT to establish whether those people are also on the public housing application list and what type of property might be required. The information might form the evidence basis for forward planning of the capital (purchase and construct) program.

Opportunity 1: Bring the housing and disability support application processes together.

Consolidation of the Disability ACT Registration of Interest and the application of housing support may increase the likelihood of smooth accommodation transition for applicants.

That way, people with a disability who apply to Housing ACT would become known to

Disability ACT and proactive support considerations could be made earlier. This could include „trigger points‟ in the intake processes of Therapy ACT, Disability ACT

Registration of Interest or application for housing assistance through Housing ACT. If a person was identified as having certain characteristics, the system may trigger referral to other parts of the Department. This approach could ensure that if a person approached one area of DHCS, and consented, all relevant areas could be advised of their pertinent circumstances. This also accords with Future Directions ‟ Strategic Priority 5 - I want to tell my story once. This could be supported by a formal, objective assessment of need that highlighted therapeutic, housing, support and other needs of the individual.

Opportunity 2: Assist people choose possible house sharing mates.

One area of struggle for people who are looking for supported accommodation alternatives is finding a suitable housemate. On a number of occasions, group living arrangements have been established and maintained based on similarity of support need, rather than the preferences of individuals. If a common way of registering an interest in shared accommodation was established it might provide people more robust information on who else might be interested in sharing accommodation, and other resources.

30

Action 5: Develop comprehensive information for people on the available accommodation models in the ACT.

A frustration for people seeking accommodation support is the lack of holistic information on accommodation models available in the ACT. This project attempted to review the available models for people with high and complex needs, but the scope did not include models for people with lower needs. A single, concise and comprehensive „information pack‟ could be developed and made available to families and individuals when they first start thinking about accommodation that would, to some extent, reduce the frustration and need for people to research their own accommodation options in every situation.

31

Comparative analysis of accommodation

The following table identifies a comparison of the accommodation models and house designs discussed in this report. The table should be read as indicative potential uses of the options. It should not be considered descriptive of actual support or size of properties, as each person's support needs are different.

Accommodation

Model

Dispersed

House design

Independent living

Suitable for... Number of residents

Number of paid support staff

Overnight support

Comparative efficiency

All people 1 0.5 -1 0-1 Baseline model.

Dual occupancy Independent living

All people 2-3 1 1 More efficient than a dispersed model, but restricts personal choice in where to live.

Triple occupancy Independent living

All people

Cluster Independent living

All people

3-6 1-3 1 More efficient than a duplex or dual occupancy, but risks negative identification of site.

4unknown unknown unknown Clusters achieve significant support efficiencies over other models, but provide comparatively lower quality of life outcomes for individuals.

32

Accommodation

Model

Intentional community

House design

Independent living

Suitable for... Number of residents

Number of paid support staff

Overnight support

Comparative efficiency

People who choose to

6-20 4-14 3-8 Intentional communities potentially have similar efficiencies to cluster models.

Intentional communities are suitable for people who choose to be part of the community on the premise it is established.

2-2.5 1 Dispersed Split housing with shared facilities

People with high physical needs

5-6

Dual occupancy Split housing with shared facilities

People with high physical needs

10-12 3-5 1-2

Similar support cost to a group home

(dispersed) model with increased quality of life potential.

More cost efficient than a dispersed split housing model, but the site needs to be carefully chosen to minimise risk of institutionalisation and negative exposure for the residents.

Triple occupancy Split housing with shared facilities

Not feasible Locating three split houses of the size necessary on one site would not be a feasible model for the ACT at this time as it may run the risk of institutionalisation and negative exposure for the residents.

33

Accommodation

Model

Cluster

House design

Split housing with shared facilities

Suitable for... Number of residents

Number of paid support staff

Overnight support

Comparative efficiency