Systematic Observation of Behaviors of Winning

advertisement

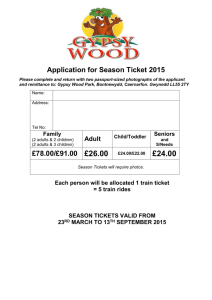

JOURNAL OF TEACHING IN PHYSICAL EDUCATION, 1985, 4, 256-270 Systematic Observation of Behaviors of Winning High School Head Football Coaches Alan C. Lacy Texas Christian University Paul W. Darst Arizona State University The purpose of the study was to analyze the teachinglcoachingbehaviors of winning high school head football coaches during practice sessions. A systematic observation instmment with 11 specifically defined behavior categories was utilized to collect data on behaviors of 10 experienced winning coaches in the Phoenix, Arizona, metropolitan area during the 1982 season. Each coach was observed in three phases of the season: preseason, early season, and late season. Segments of the observed practices were classified as warm-up, group, team, or conditioning. Analysis of the data showed that the total rate per minute (RPM) for behaviors was higher in preseason than in either of the other two phases. Four of the 11 defined behavior categories (praise, scold, instruction, positive modeling) had significant differences (.05 level) in RPM between the preseason and the other two phases of the season. No significant differences were found between the early season and the late season phases. The group segment was used most in the preseason, while the team segment was used more of the time in the early season and late season. A lower RPM during the warm-up and conditioning segments indicated less involvement by the head coaches than in the group and team segments of practice. It would seem beneficial to teachers and coaches if systematic observational research were to be focused on the behaviors of winning coaches of different sports at various levels of athletic competition (youth sports, high school, college, etc.). The use of systematic observation instruments enables researchers to report objective findings on the behavior of coaches. Completed research using systematic observation in athletic/coaching environments is not widespread. However, several studies have been completed using behavior categories similar to the coaching behaviors defined and observed in this study. Tharp and Gallimore (1976) devised a 10-category system for systematic observation in a teachinglcoaching setting. This system was designed to observe John Wooden, basketball coach at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), during 15 practice sessions spread over the final two-thirds of the 1974-1975 season. The investigators reported that more than half of Wooden's behavior was in the instruction category. Another Request reprints from Alan C. Lacy, Dept. of Kinesiological Studies, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX 76219. BEHAVIORS OF WIN'NING FOOTBALL COACHES 257 interesting finding was that the number of praises (6.9% of all behaviors) was almost equal to the number of scolds (6.6% of all behaviors). Williams (1978) employed a modified replication of the Tharp and Gallimore instrument to systematically observe a successful high school head basketball coach. Williams observed practices twice a week throughout the season and gathered data using event-recording procedures. The results were compared to those of Tharp and Gallimore's study on Wooden. The findings indicated that the high school coach emphasized instruction, as did Wooden, but used praise (25% of all behaviors) much more frequently than Wooden did. Williams suggested that the differences in maturity, skill level, and motivation of players at the high school and college levels could possibly explain this disparity in the use of praise. Langsdorf (1979) used an observation instrument based on the Tharp and Gallimore (1976) research to objectively observe the coaching behavior of Frank Kush, head football coach at Arizona State University, during 18 spring practice sessions. Findings of this research showed the greatest percentage of behavior for Kush occurred in the instruction category, followed by the hustle and scoldlreinstruction categories. Praise was the fourth most frequently displayed behavior and was almost equal to the percentage of the scold category. A majority of scold statements were followed by behaviors of an instructive nature. Behaviors were analyzed according to the segment of practice in which they occurred. Kush's behaviors varied according to the segment of practice. The conditioning segment was high in the hustle category, the individual work segment was high in the praise category, and the scrimmage segment was high in the scold category. Another facet of this study was the comparison of behavior percentages of each category for Kush and Wooden. A Spearman rho rank-order correlation coefficient of 3 5 , significant at the .O1 level of confidence, showed close similarities in the behaviors of the two coaches. Kush, however, had higher percentages in both the praise and scold categories, even though both coaches utilized the two categories in almost a one-to-one ratio. Wooden's percentage in the instruction category exceeded Kush's by approximately 15%. A data base is slowly emerging as findings are reported from research using systematic observation in the athleticlcoaching environment. This can be a beginning to the development of a more complete understanding of the science of coaching. The purpose of the study was to analyze the teachinglcoaching behaviors of winning high school head football coaches during practice sessions by using an objective method of systematic observation. Methods Subjects The subjects for this study were 10 high school head football coaches in AAA classification (mininum 1,600 pupil enrollment) schools in the Phoenix, Arizona, metropolitan area. Each subject was required to have at least 4 years' experience as a head football coach at the varsity high school level and .600 or higher career winning percentage. Collectively, these coaches had compiled a 735-302-21 record in 98 seasons for a winning percentage of .709. 258 LACY AND DARST Phases of the Season For purposes of the study, the season was divided into three phases. The preseason phase was August 23 through September 3, the early season phase was September 13 through October 4, the late season phase was October 18 through November 10. Each coach was observed once in each phase. Thus, each coach was observed three times with behaviors being recorded over a total of 30 practice sessions for the 10 subjects. During the early and late season phases, practices were observed on Monday, Tuesday, or Wednesday. Thursday and Saturday practices were not observed because normally they were light practices before and after the Friday night game. None of the coaches was observed on the same day in early and late season phases. There was a five-game interval between observations for each coach in these two phases. The day of observation in the preseason was not considered important, since no games were scheduled during this phase. Segments of the Practice Sessions In order to observe and analyze the behaviors of the head coach during specific parts of the workout, practice segments for this study were described as follows: 1. Warm-up: Typically, this was the first segment of a practice session designed to prepare the athletes for strenuous activity. It could include stretching, calisthenics, isometric exercises designed to strengthen the musculature of the neck, and footworldagility drills. 2. Group: This segment involved separating the team into combinations of positions to work on specific skills or strategies. 3. Team: This segment incorporated a gamelike situation in which all 11 members of the offensive, defensive, or kicking teams worked together. Usually this portion of practice involved the starters (first team) working against nonstarting teammates to simulate game conditions. 4. Conditioning: This was a short portion or practice consisting of various forms of running to improve muscular and cardiovascular endurance. Some teams included short bursts of push-ups, sit-ups, and so forth, in their conditioning. Behavior Categories Eleven specific categories of coaching behavior were included in this systematic observation system modified from Tharp and Gallimore (1976). These behavior categories were defined as follows: when e speaking directly 1. Use ofjrst name: Using the first name or ~ ~ k I I a m to a player, for example, "Bill, nice block!" or "That was a poor tackle, Tank." 2. Praise: Verbal compliments or statements of acceptance, such as "Nice going, gang" or "Great catch." 3. Scold: Verbal statements of displeasure such as "That was a terrible effort!" or "You looked awful on that play." 4. Instruction: Verbal statements to the players referring to fundamentals or strategies of the game, which can come in the form of questioning (e.g., "Who do you block on 44 dive?"), corrective feedback (e.g., "You didn't keep your BEHAVIORS OF WINNING FOOTBALL COACHES 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 259 feet moving on that block"), direct statements (e.g., "Block down on the tackle of 26 blast"), or statements of strategy (e.g., "Against Mesa High we must rush their passer"). Hwtle: Verbal statements intended to intensify the efforts of the players, such as "Be quick, be quick" or "Push yourself, push yourself." Nonverbal reward: Nonverbal compliments or signs of acceptance such as a smile or a pat on the back. Nonverbalpunishment: Nonverbal behaviors of displeasure such as kicking the ground, throwing a clipboard, or slapping a player's helmet. Positive modeling: A demonstration of correct performance of a skill or playing technique. Negative modeling: A demonstration of incorrect performance of a skill or playing technique. Management: Verbal statements related to organizational details of practice session not referring to strategies or fundamentals of the game; verbal interaction with assistant coaches (e.g., "Give me three lines facing me on the goal line" or "Coach, is your group ready for team offense?"). Other: Any behavior that cannot be seen or heard clearly or that does not fall into the above categories such as checking injuries, joking with players, or talking with bystanders. Data Collection Procedures The procedure used for data collection in this investigation is known as event recording, which is a cumulative record of the number of discrete events occurring within a specified time (Siedentop, 1976). Each time a specified predefined behavior was observed, that behavior was recorded on the coding sheet. Each practice segment observed was timed to the nearest minute for the purpose of determining the rate per minute (RPM)of each behavior category occurring during that particular part of the workout. Checks for interobserver agreement (IOA) were made in the first week of each phase of the season to ensure the accuracy of the coding procedures of the investigator. During IOA checks the independent observer and the investigator were situated far enough apart so that neither could influence the behavior being recorded by the other. The percentage of IOA agreement was determined by dividing the agreements by the sum of the agreements and disagreements and then multiplying by 100. In observational studies, two independent observers must be able to obtain 85 % agreement on what they observe and record (Siedentop, 1976). Data Analysis A Fortran computer program was used to perform the quantitative analysis of the observed coaching behaviors. Analysis of variance with repeated measures pixon & Brown, 1977) was used to statistically determine if significant differences existed at the .05 level of confidence between the means of the various coaching behavior categories in the different phases of the season. The per-comparison alpha level was adjusted to correct for an inflated experimentwide alpha error rate that would occur with multiple dependent variables (Games, 1971). With those means indicating a significant difference at the adjusted alpha level, a post hoc Tukey's test (Bartz, 1981) was administered to determine the exact nature of the dif- LACY AND DARST 260 ferences between phase. The numbers of behaviors were totaled for each category of coaching behavior in order to determine the percentage and RPM of total behaviors exhibited for the group of coaches for each practice segment and for each phase of the season. By definition, the use-of-first-name behavior always occurred in conjunction with another behavior. The number of occurrences of first name use was subtracted from the total number of behaviors before percentages of each of the other behavior categories were calculated. If this were not done, the percentages of each category would decrease and the true percentages would be distorted. The percentage of behaviors accompanied by the use of first name should be considered separately from the percentages calculated in the other behavior categories. Results The interobserver agreement percentage for the preseason check was 93 % ,for the early season check it was 95.3%, for the late season check it was 98.4%, and for the total season it was 96.4%. These IOA percentages are in excess of the required 85 % as determined by Siedentop (1976). A summary of each behavior category for each phase of the season is shown in Table 1. Season totals for each behavior are also included. The number of behaviors, rates per minute, and percentages in the table represent overall behaviors for the group of subjects. More behaviors were recorded in the preseason phase than in either of the other two phases. This plus the fact there were fewer minutes of observation in the preseason Table 1 Comparison of Behaviors by Phases Behavior category Total RPM 010 Total Preseason First name Praise Scold Instruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other Total behaviors minutes RPM .70 .60 .32 1.88 .72 .02 .01 .15 .05 .77 .09 RPM Early season 630 380 158 1,837 670 8 10 91 29 767 67 . a .50 .30 .13 1.46 .53 .06 .08 .07 .02 .61 .05 010 BEHAVIORS OF WINNING FOOTBALL COACHES 261 Table 1 (cont.) Behavior category Total First name Praise Scold Instruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other 548 390 163 1,445 666 31 21 62 24 613 73 Total behaviors minutes RPM 4,036 1,099 RPM Late season .50 .36 .15 1.32 .61 .03 .02 .06 .02 .56 .07 Oh 15.7* 11.2 4.7 41.4 19.1 .9 .6 1.8 .7 17.6 2.1 Total 1,955 1,434 669 5,356 2,134 60 41 323 110 2,229 239 RPM Entire season .56 .41 .19 1.55 .62 .02 .01 .09 .03 .64 .07 010 15.5' 11.4 5.3 42.5 16.9 .5 .3 2.5 .9 17.7 1.9 14,550 3,464 3.67 4.20 *Denotes percentage of behaviors accompanied by use of first name. caused the RPM to be much higher than for the early and late season phases. The total RPM in the preseason was 5.31, as compared to 3.70 in the early season and 3.67 in the late season. Further, every behavior category except nonverbal punishment and nonverbal reward showed a higher RPM in the preseason than in either of the other two phases. Because of a lower number of total behaviors in the early and late season phases, the behavior percentages showed no such trend. None of the 11 mean percentages of behavior was found to differ significantly between phases. However, 4 of the 11 mean RPMs proved to be significantly different between phases. They were the behavior categories of praise, scold, instruction, and positive modeling. In each of the four behaviors a significant difference occurred at the .05 level of confidencebetween the preseason phase and both the early and late season phases. There was no significant difference in any of the four behaviors between the early and late season phases. These findings are illustrated by Figures 1 through 4. To obtain a more complete description of the coaching behaviors of the group of subjects, the data were analyzed by comparing each segment of the practice session (warmup, group, team, conditioning) across the phases of the season. The data are illustrated in Tables 2-5. A comparison of segments for the total season is illustrated in Table 6. Most behaviors exhibited throughout the season occurred in either the group segment or the team segment, the group segment accounting for 42.4% of total behaviors and the team segment totaling 45.5 %. Seven percent of total behavior exhibited occurred in the warmup segment, while conditioning accounted for 5%. The total RPM was higher in the group segment, 5.48, than in any other segment. The team segment RPM was 3.78, followed by the warm-up RPM of 3.05 and conditioning RPM at 2.93. - p l o 3 30 ~ asn JOJ saseqd uaaMjaq sneam y sa3uaiafia -as!=% 30 asn JOJ saseqd uaadljaq msam m sa3uaiama - amZ!& - 1 amZ!a BEHAVIORS OF WINNING FOOTBALL COACHES INSTRUCTION (RPM) Mean 2 SEM Preseason Figure 3 Early Season Late Season - Differences in means between phases for use of Instruction. POSITIVE MODELING WPM) Mean i SEM Preseason Figure 4 Early Season Late Season - Differences in means between phases for use of Positive Modeling. LACY AND DARST Table 2 Comparison of Behaviors in Warm-up Segments by Phases Behavior category Total RPM Yo Total Preseason First name Praise Scold lnstruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other .303 .270 .I23 1.270 1.139 .016 RPM Early season 31 9 5 62 113 0 0 5 1 66 16 .272 ,079 ,044 549 .991 - .049 .009 .579 .I40 Total behaviors minutes RPM 010 behaviors of phase Late season First name Praise Scold lnstruction , Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other Total behaviors minutes RPM % behaviors of phase *See note, Table 1. .235 .I33 .082 .357 .765 .082 - .01 .316 .204 Entire season 91 55 28 252 327 10 0 13 2 169 72 .272 .I65 .084 .755 .979 .03 - ,039 .006 506 .216 Oh BEHAVIORS OF WINNING FOOTBALL COACHES Table 3 Comparison of Behaviors in Group Segments by Phases Behavior category Total First name Praise Scold lnstruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other RPM Preseason .95 .96 .40 2.42 .72 .01 .02 .28 .ll .91 .06 Yo Total 230 193 47 759 203 3 3 57 23 258 24 RPM Early season .55 .46 .ll 1.82 .49 .O1 .01 .14 .06 .62 .06 Total behaviors minutes RPM O h behaviors of phase First name Praise Scold Instruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other Total behaviors minutes RPM O h behaviors " See note, Table 1. Late season .80 .65 .15 1.82 .70 .01 .02 .ll .04 .72 .06 861 791 263 2,316 706 11 15 210 81 854 65 Entire season .76 .70 .23 2.06 .63 .O1 .01 .19 .07 .76 .06 YO LACY AND DARST Table 4 Comparison of Behaviors in Team Segments by Phases Behavior category Total First name Praise Scold lnstruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other RPM 010 Preseason .63 .41 .33 1.79 .54 .03 .O1 .08 .01 .71 .05 15.9' 10.4 8.3 45.1 13.7 .8 .2 2.1 .3 17.9 1.1 Total behaviors minutes RPM 010 behaviors of phase First name Praise Scold Instruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other Total behaviors minutes RPM 010 behaviors of phase *See note, Table 1. Total RPM 347 167 103 996 266 4 7 29 5 383 20 Early season .54 .26 .16 1.54 .41 .01 .01 .05 .01 .59 .03 915 540 360 2,717 785 38 26 98 26 1,046 69 Entire season .52 .31 .21 1.55 .45 .02 .O1 .06 .01 .60 .04 34.8 Late season .44 .29 .17 1.41 .42 .03 .02 .05 .02 .53 .04 2,254 657 14.8* 9.7 5.6 47.1 14.2 1.O .8 1.6 .8 17.7 1.5 010 267 BEHAVIORS OF WINNING FOOTBALL COACHES Table 5 Comparison of Behaviors in Conditioning Segments by Phases Behavior category Total First name Praise Scold lnstruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other Total behaviors minutes RPM % behaviors of phase First name Praise Scold Instruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other Total behaviors minutes RPM % behaviors of phase *See note, Table 1. RPM Preseason .40 .18 .08 .36 1.08 0 0 .O1 .01 .58 .18 010 Total RPM Early season .29 .14 .04 .26 1.14 .O1 0 0 0 .78 .09 2.89 Late season .35 .24 .09 .23 1.52 0 0 .O1 0 .57 .ll 3.13 Entire season .35 .19 .07 .28 1.24 .01 0 .O1 .01 .63 .13 Yo LACY AND DARST Table 6 Comparison of Behaviors by Segments for Total Season Behavior category Total RPM Warm-up First name Praise Scold Instruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other .27 .I6 .08 .75 .98 .03 - .04 .01 .51 .22 YO Total RPM 010 Group .76 .70 .23 2.06 .63 .O1 .01 .19 .07 .76 .06 Total behaviors minutes RPM 010 behaviors of season Team First name Praise Scold Instruction Hustle N-V reward N-V punish. Pos. model. Neg. model. Management Other .52 .31 .21 1.55 .45 .02 .01 .06 .O1 .60 .04 Conditioning .35 .19 .07 .28 1.24 .01 - .01 .01 .63 .13 Total behaviors minutes RPM % behaviors of season Figuresfor the entire group of segments are identical to those listed in Table 1 for the entire season. *See note, Table 1. BEHAVIORS OF WINNING FOOTBALL COACHES 269 The instruction category dominated the group and team segments and accounted for 42.5% of all behaviors during the season. The hustle category was most widely used in both the warm-up and conditioning segments. Hustle ranked third in RPM and percentage behind the management category during the total season. Discussion The total rate per minute for behaviors was higher in the preseason (5.31) than in either the early (3.70) or late season (3.67) phases. The behavior categories of praise, scold, instruction, and positive modeling were significantly different between phases. Results of a Tukey test showed the preseason RPM for each of the four categories was significantly higher than the other two phases. There were no significant differences between the early and late season phases. This indicates a more intense teaching style by coaches in the first part of the year as they concentrate on basic fundamentals and individual skills. This is further reinforced by the fact that the group segment was used most extensively in the preseason. During the early and late season, the team segment was employed more frequently than other segments. In these parts of the season, coaches turn their attention to preparing for the next opponent and emphasizing team strategies. The lower RPM of head coaches during the warm-up and conditioning segments of practice showed a less active involvement during these short portions of practice. Typically, assistant coaches and team leaders led these segments. The hustle behavior category was the most highly observed behavior among the head coaches during these two segments. Thus, the major function of the subjects was to encourage better effort in these segments. Praise was used more often in the group segment (.70 RPM) than other segments, as was the scold category (.23 RPM).Across the entire season, praise was used over twice as much as scold. This reinforces the popular opinion that more can be accomplished by the coach using positive rather than negative interactions (Cratty, 1973; Singer, 1972; Tutko & Richards, 1971; Wilson, Buzzell, & Jensen, 1975). The instruction category was used more than twice as often as any other behavior in every phase of the season. Across the entire season it dominated the group and team segments. These findings support the idea that informational feedback is a prerequisite for effective teachinglcoaching. The dominant nature of the instruction category is not surprising, given that other observational studies using similar categories (Langsdorf, 1979; Tharp & Gallimore, 1976; Williams, 1978) have reported comparable results. Since it is apparent that the instruction behavior category is used extensively, it should be subdivided into more specific categories for further examination. Suggested categories (Lacy & Darst, 1984) are manual manipulation, questioning, preinstruction, concurrent instruction, and postinstruction. Coaches should utilize observational instruments to aid in objective self-evaluation of individual behaviors. By becoming aware of their behavioral habits, they can possibly modify their behaviors to become more effective coacheslteachers. Additional observational research of this nature can further enhance understanding of the science of teaching and coaching. Recommendations for further study would be 270 LACY AND DARST to complete investigations focusing on groups of coaches at various levels of competition involved in individual as well as team sports. Comparison of behaviors of winning and losing coaches would also be of value. References Bartz, A.E. (1981). Basic statistical concepts (2nd ed.). Minneapolis: Burgess. Cratty, B.J. (1973). Psychology in contemporary sport. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Dixon, W.J., & Brown, M.D. (Eds.) (1977). Biomedical computer programs P-series. Berkeley: University of California Press. Games, P.A. (1971). Multiple comparison of means. American Educational Research J o u m l , 8 , 531-565. Lacy, A.C., & Darst, P.D. (1984). The evaluation of a systematic observation instrument. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 3(3), 59-66. Langsdorf, E.V. (1979). A systematic observation of football coaching behavior in a major university environment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University. Siedentop, D. (1976). Developing teaching skills in physical education. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin. Singer, R.N. (1972). Coaching, athletics, and psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill. Tharp, R.G., & Gallimore, R. (1976). What a coach can teach a teacher. Psychology Today, 9(8), 75-78. Tutko, T.A., & Richards, J.W. (1971). Psychology of coaching. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Williams, J.K. (1978). A behavioral analysis of a successful high school basketball coach. Unpublished master's thesis, Arizona State University. Wilson, S., Buzzell, N., & Jensen, M. (1975). Observational research: A practical tool. Ihe Physical Educator, 32(2), 90-93.