SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY AS A TOOL FOR UNDERSTANDING

SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY AS A TOOL FOR UNDERSTANDING

RELATIONSHIPS IN FICTION: APPLICATIONS TO THE WORKS

OF PETRUS ALFONSI, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, JAMES

JOYCE, ANNE TYLER, AND NICK HORNBY

THESIS

Presented to the Graduate Council of

Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree

Master of ARTS by

Billy Joe Lancaster

San Marcos, Texas

May 2011

SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY AS A TOOL FOR UNDERSTANDING

RELATIONSHIPS IN FICTION: APPLICATIONS TO THE WORKS

OF PETRUS ALFONSI, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, JAMES

JOYCE, ANNE TYLER, AND NICK HORNBY

Committee Members Approved:

Approved:

____________________________

J. Michael Willoughby

Dean of the Graduate College

________________________________

Priscilla V. Leder, Chair

________________________________

Paul N. Cohen

________________________________

Sally Caldwell

COPYRIGHT by

Billy Joe Lancaster

2011

FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT

Fair Use

This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author‘s express written permission is not allowed.

Duplication Permission

As the copyright holder of this work I, Billy J. Lancaster, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First, I want to acknowledge my Lord, Jesus the Christ the Son of the Living God, for hearing my many prayers and for His faithfulness even when I failed.

I thank those writers and scholars, living and dead, whose works are a part of my work, whose creations and endeavors allowed me to move forward with my own.

I thank my family without whose encouragement, understanding, and support I would not have been able to complete this task.

I thank the committee who oversaw this thesis, especially Priscilla Leder, who questioned everything and in doing so assisted me in creating a solid work.

And I thank my friends, the cheering section who stuck with me to the end: Jonna,

Jason, Sean, Steve, Will, and especially Lora, whose assumption of my abilities berated me into believing I could finish.

This manuscript was submitted on February 22, 2011. v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................v

ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... ix

CHAPTER

I.

INTRODUCTION: THEORETICAL CRITICISM IN MIMETIC CONTEXT

AND SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY ...........................................................1

The Basics of Social Exchange Theory .......................................................2

Additional Concepts.....................................................................................6

The Range of Application ..........................................................................15

II.

RELATIONSHIPS IN ALFONSI‘S DISCIPLINA CLERICALIS ...................17

Significance of the Disciplina Clericalis ...................................................17

Medieval Children‘s Literature ..................................................................20

Application of Social Exchange Theory ....................................................21

III.

MOTIVE IN THE ATTITUDES, ACTIONS, AND ARGUMENTS OF

SHAKESPEARE‘S TOUCHSTONE AND JAQUES.....................................27

Behavior as Exchange in Shakespeare‘s Work ..........................................28

Rhetorical Abilities in Jaques and Touchstone ..........................................29

Exchange Theory and Motive in Shakespeare‘s Characters ......................31

Motive and Jaques................................................................................31

Motive and Touchstone........................................................................34 vi

IV.

UNEQUAL PAIRINGS IN JOYCE‘S ―LITTLE CLOUD‖ AND

COUNTERPARTS‖ ........................................................................................37

Social Exchange in ―A Little Cloud‖ .........................................................38

Social Exchange in ―Counterparts‖ ...........................................................43

V.

RELATIONSHIPS IN TYLER‘S

LADDER OF YEARS .................................49

Familiarity in the Works of Anne Tyler ....................................................49

Typical Relationships in Ladder of Years ..................................................51

Spousal Relationships ..........................................................................51

Heterosexual Romantic Relationships .................................................54

Parent-Child Relationships ..................................................................57

Further Suggestions ...................................................................................59

VI.

RELATIONSHIPS IN HORNBY‘S

A LONG WAY DOWN ...........................60

Atypical Relationships in Hornby‘s Work .................................................60

Suicide as the Dissolution of Relationships ...............................................62

Martin ...................................................................................................64

Maureen ...............................................................................................65

Jess .......................................................................................................66

JJ ..........................................................................................................67

Atypical Relationships Through Social Exchange Theory ........................68

Martin ...................................................................................................71

Maureen ...............................................................................................73

Jess .......................................................................................................75

JJ ..........................................................................................................77

Further Suggestions ...................................................................................79 vii

VII.

CONCLUSION: SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY AS LITERARY

CRITICISM .....................................................................................................80

The Range of Applicability ........................................................................80

A New Literary Theory ..............................................................................82

WORKS CITED ....................................................................................................85

viii

ABSTRACT

SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY AS A TOOL FOR UNDERSTANDING

RELATIONSHIPS IN FICTION: APPLICATIONS TO THE WORKS

OF PETRUS ALFONSI, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, JAMES

JOYCE, ANNE TYLER, AND NICK HORNBY by

Billy J. Lancaster, B.A.

Texas State University-San Marcos

2011

SUPERVISING PROFESSOR: PRISCILLA LEDER

An analysis of Petrus Alfonsi‘s

Disciplina Clericalis

, William Shakespeare‘s

As

You Like It

, James Joyce‘s

Dubliners , Anne Tyler‘s Ladder of Years

, and Nick Hornby‘s

A Long Way Down illustrates the nearly universal applicability of social exchange theory as a lens for understanding the motives and relationships of literary characters. An application of theory to fiction within a mimetic context lies at the heart of some of the most popular and important methods for the contemporary interpretation of literature and, by extension, theoretical literary criticism. These mimetic forms, these applications of ix

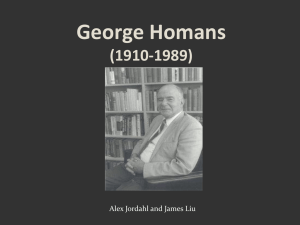

real-life ideologies, philosophies, and sciences, are part of an ever-expanding list of tools available to literary scholars attempting to draw clearer meanings from texts. Social exchange theory, posited by Homans in ―Social Behavior as Exchange‖ and expounded on in his seminal article‘s follow-up, Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms , explains the dynamics of relationships by observing how behavior is traded as a commodity between and among members of a group (two or more) and uses the economic formula of profit equals reward minus cost (P=R-C) to reveal a person‘s motives when acting within the group. This thesis adds George Homans‘s social exchange theory to the mimetic toolbox of theoretical literary criticism. x

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION: THEORETICAL CRITICISM IN MIMETIC

CONTEXT AND SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

An application of theory to fiction within a mimetic context lies at the heart of some of the most popular and important methods for the contemporary interpretation of literature and, by extension, theoretical literary criticism. Bernard Paris, in his discussion of psychology and fiction, ―argues that [psychoanalytic] theories can also be applied in a mimetic context to help us understand fictional characters‖ (Keesey 215). In the late eighteenth century Mary Wollstonecraft published her radical treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman , the vanguard of the feminist movement, and about 150 years later,

Simone de Beauvoir, with The Second Sex, pulled feminism fully into the field of literary analysis. With the publication of The Communist Manifesto , Karl Marx introduced to the world to the idea of class struggle, and riding on the weight of his philosophies, economics became an important consideration in literary criticism. Freud‘s groundbreaking work in the field of psychoanalysis was applied to literature almost immediately, giving rise to various schools of criticism with roots in psychology, including the use of Murray Bowen‘s family systems theory. These mimetic forms, these applications of real-life ideologies, philosophies, and sciences, are part of an everexpanding list of tools available to literary scholars attempting to draw clearer meanings from texts. This thesis adds George Homans‘s social exchange theory to the mimetic toolbox of theoretical literary criticism.

1

Sarah Schiff‘s ―Family Systems Theory as Literary Analysis: The Case of Phillip

Roth‖ stands as a good example of how a theory created by one discipline, psychology,

2 for use with actual people, can be applied to fictional characters in literature. Schiff presents Bowen‘s family systems theory as a means to interpret fiction, giving, as an example for further critical use, her application to Roth‘s work and revealing, within the text, purposes and motivations not otherwise seen though traditional psychoanalytic interpretation. Likewise, this thesis demonstrates how Homans‘s social exchange theory can be used to interpret characters‘ actions using the disparate works of authors ranging from medieval to contemporary times. An analysis of Petrus Alfonsi‘s Disciplina

Clericalis

, William Shakespeare‘s

As You Like It

, James Joyce‘s

Dubliners

, Anne Tyler‘s

Ladder of Years

, and Nick Hornby‘s

A Long Way Down illustrates the near-universal applicability of social exchange theory as a lens for understanding the motives and relationships of literary characters.

The Basics of Social Exchange Theory

Before delving into an application of theory to literature, or even how the theory should be used with literature, readers need an explanation of how social exchange theory works. Social exchange theory, posited by Homans in ―Social Behavior as Exchange‖ and expounded on in his seminal article‘s follow-up,

Social Behavior: Its Elementary

Forms , explains the dynamics of relationships by observing how behavior is traded as a commodity between and among members of a group (two or more) and uses the economic formula of profit equals reward minus cost (P=R-C) to reveal a person‘s motives when acting within the group (603). Homans describes how a combination of B.

F. Skinner‘s work in behavioral psychology, both field and laboratory small-group

research, the dynamics of influences, and, as the title of his work suggests, economics

3 informs social exchange theory (597). Because Homans, as most scholarly writers in the

1950s, uses a generic ―he‖ to denote any individual, I am adopting his usage for the sake of clarity within this thesis.

To better understand the behavior as exchange concepts, consider a classroom example, using the following designators for the various group members: Professor,

Student, Other (for one other student), and Classmates (to represent the remaining student group). The student-teacher relationship during a seminar class in which students are expected to participate in discussion exemplifies behavior as exchange. The class costs

Student in money for tuition and time for study, and, in this example, Student provides insight—incurring further costs with the possibility of failure—into a statement by

Professor. Student receives positive feedback from Professor (reward), which extends

Student‘s knowledge, provides guidance for further study, and increases Student‘s status among Classmates (profit). Professor, who has invested time and money in research, also profits in the relationship through satisfaction with successful students and money for teaching the class. This simplified illustration, which I continue throughout the chapter, illustrates Homans‘s ―view that interaction between persons is an exchange of goods, material and non-material‖ (―Exchange‖ 597). Homans expounds further on this idea in his later work, when he states that he ―envisages social behavior as an exchange of activity, tangible and intangible, and more or less rewarding or costly between at least two persons‖ (

Social 13).

Homans‘s concepts include all behaviors and materials traded between and among members of a group, but a single encounter with another individual is not considered a

relationship. For example, the exchange of money for goods in a store between a clerk

4 and a customer, with additional polite comments included, does not constitute a relationship because the exchange is a single instance rather than ongoing. However, if the customer regularly frequents the store, the repeated exchange of money for goods could begin to include other costs and rewards for the two individuals, such as a secure knowledge of the availability of the desired products and a comforting smile offered by the clerk, as well as the feelings of accomplishment and monetary security for the clerk who helped to establish a repeat customer. The continued and growing exchange between the two constitutes a relationship, a group of two, albeit with limited boundaries.

Homans looks at relationships using an amalgam of sociological, behavioral, and economic theories which informs his view of behavior as exchange in what has come to be known as social exchange theory, and several specific observations are necessary for an understanding of Homans‘s theory. The most important of these observations, given in

―Social Behavior as Exchange,‖ come from Homans as suggestive statements of what a social exchange theory should contain:

1.

Social behavior is an exchange of goods, material goods but also nonmaterial ones, such as the symbols of approval or prestige.

2.

Persons that give much to others try to get much from them, and persons that get much from others are under pressure to give much to them.

3.

This process of influence tends to work out at equilibrium to a balance in the exchanges.

4.

For a person engaged in exchange, what he gives may be a cost to him, just as what he gets may be a reward, and his behavior changes less as profit, that is, reward less cost, tends to a maximum.

5.

Not only does he seek a maximum for himself, but he tries to see to it that no one in his group makes more profit than he does.

6.

The cost and the value of what he gives and of what he gets vary with the quantity of what he gives and gets. (606 numeration added)

While these statements are the most important for an understanding of Homans‘s theory, other points need to be emphasized or expounded upon as well for our particular

5 investigation of the texts by Alfonsi, Shakespeare, Joyce, Tyler, and Hornby. First, when a person is rewarded for certain behaviors, he will tend to increase those behaviors until he is satiated with the reward or the reward for those behaviors is withdrawn. Second, a group exerts pressure by withholding sociologically valuable rewards (intrinsic or extrinsic) from deviant members and will minimize interaction with those members.

Third, Homans‘s application to relationships of the economic formula of P=R–C, explaining how behaviors are exchanged in small groups, concludes that change is greatest when profit is least (―Exchange‖ 603). Therefore, if the profit among members of a group or partners in a relationship is high, the participants have no reason to change the functioning of the group.

Using our classroom example, Student‘s input during the seminar increases as

Professor and Classmates progressively expect more from Student and as Professor and

Classmates acknowledge Student‘s abilities. If Other, however, gives input that is off topic or in error, he, or at least his answers, will be shunned by Classmates as this is

considered deviant behavior that is not acceptable in the class. If Other does not amend

6 his behavior, he will not only face the derision of Classmates but Professor will deny valuable rewards in terms of grades.

Additional Concepts

In addition to those particular observations, a social exchange critic needs an awareness of the additional work done with the theory since its inception. In Social

Behavior: Its Elementary Forms , the follow-up to his 1958 article, Homans examines how his theory relates to several concepts and related propositions made in research connected to exchange in social behavior, including influence, conformity, esteem, sentiment, interaction, distributive justice, authority, and equality. Many of these concepts are overlapping and interconnected, one relating to, reflecting, or building on another.

Influence , affecting change in another person, constitutes a social exchange when any one of a particular set of social aspects becomes a reward for the person being changed: approval, acceptance, similarity, agreement with opinions, or material rewards.

In our example, Professor, through valuable social rewards, changes Student‘s behavior

(whether consciously or unconsciously does not matter) from giving hesitant answers to direct questions to participating regularly and confidently in class discussion.

Likewise, conformity is effective in groups that have achieved practical equilibrium , a state wherein a group has more or less worked out a consistent set of norms. Conformity seems related—as many of these concepts are intertwined—to influence, in that an individual‘s behavior is being changed; however, the method of reward differs between the two. Homans explains, ―People that find conformity valuable

reward conformers with social approval, but they withhold approval from those that will

7 not conform, or even express positive dislike for nonconformists as having denied them a reward they had the right to expect‖ (

Social 129). Other experiences this phenomenon in negative treatment by Classmates and in the correction of his information by Professor. In order for Other to regain status and approval, he must increase acceptable behaviors, adding insightful, helpful, or at least correct comments during class discussion. Whereas with influence behavior is changed in order to receive a reward (approval, thanks, etc.), with conformity, rewards (specifically, association with the group) are withheld in order to bring about change in the individual.

While influence and conformity are generally rewarded on an equal basis, esteem belongs to those members of a group whose contributions are valued more highly than the majority of the group members. Homans, relating esteem to the economic laws of supply and demand, states that ―it is not enough that a service be rare; it must be both rare and valuable to others‖ (

Social 147). If a particular product is in great demand, its value goes up as its availability goes down. However, if the supply of a product is relatively great, the value of that product goes down. Esteem can be seen in our example when an upcoming piece of reading for the seminar class is suggested, by Professor, to be troubling or extremely challenging, and Other states that they should form a study group.

Classmates are noncommittal until Student indicates plans to attend. Classmates soon indicate their plans to attend also. Other‘s presence at the study group is not valuable to

Classmates; however, Student‘s presence, because of the obvious agreement by Professor with his opinions, makes the study group with Student‘s information available without the professorial observation, more attractive. Student‘s esteem adds value to the study

group. Furthermore, the extra time invested might be rewarded by Professor in terms of

8 extra credit or an increased participation grade. Esteem develops in ―the relation between the activities performed by the members of a group and the sentiments of liking or social approval accorded them by other members‖ (145). A member of a group who can perform a unique activity which is in demand by all or most members of the group will be held in higher esteem than a member who can only perform the basic norms required for group membership and supplied by all members. Furthermore, the approval given by those with high esteem is valued more than that given by a group member with lower esteem (170).

Though esteem and sentiment are interconnected, esteem is given to a member by other members, while sentiment remains with the esteemed member without direct regard to his particular activities within the group except that he has already been given esteem.

Sentiment is derived from the amount of esteem given from members of a group to other members as related to preferences of choice by those members. While many variables come into play to determine those preferences, Homans‘s observations indicate that those members of a group held in highest esteem, those valued most for their contributions to the group or group members, will also be those with the highest amount of sentiment given to them; i.e. those members whose esteem is greatest will receive more preferential treatment by other members of the group than those whose sentiment is lower. At the beginning of the study session, Classmates as well as Other want to be in close proximity to Student, and because Student has higher esteem than any member of the group present, the group as a whole prefers him over other members. Student is the recipient of high sentiment and the resultant preferential treatment is reflected not only in the proximal

choices made by Classmates, but also in the degree of consideration given to his positive

9 or negative opinion of others. Homans frames his findings this way: ―[T]hey tended to choose others according to the simplest principle of distributive justice: the ‗better‘ a man‘s behavior, the greater his reward in approval‖ (

Social 176). Esteem, therefore, is what is given to a member by other members while sentiment rests within the member to which esteem has been given. Student‘s ―behavior,‖ giving valuable information to the group, infuses him with sentiment from Professor and Classmates. On its simplest level, sentiment can be measured by how often members of a group show a preference for any other particular member, and the member with the highest preference rate is the one with the highest sentiment.

Continuing with the interconnectedness of these suppositions and observations, interaction relates directly to the frequency of previously discussed behaviors. Homans uses the term liking to denote the social approval given by one member of a group to another, so it follows that a group member who has both high esteem and sentiment also has a high social approval ( Social 181). And group members will interact with other members who have a high social approval with more frequency than with those whose social approval is low. Homans‘s observation that individuals repeat activities with more frequency if they are rewarded for those activities is confirmed when practical equilibrium is in effect, wherein the ―process of influence tends to work out at equilibrium to a balance in the exchanges‖ (―Exchange‖ 606). The most significant finding for our purposes relates to the direct correlation between interaction and social approval: ―the more a man interacts with another, the more he likes him‖ (Homans,

Social 203). However, Homans explains an important exception, stating that ―When the

10 costs of avoiding interaction are great enough, a man will go on interacting with another even though he finds the other‘s activity punishing,‖ and in that case, the greater the frequency of interaction, the lower the social approval becomes between the two group members (187). Other has continued his unacceptable behavior in the seminar class by arguing against accepted concepts without evidence that those concepts are wrong.

Furthermore, he provides absurd suggestions in class for the sake of humor, causing a disruption of important discussion which is needed by Classmates. Because, however, all the students need to be present in the classroom, Classmates continue interaction with

Other because the ―costs of avoiding interaction,‖ not coming to class, are greater than the costs of enduring Other‘s antics. If, as Homans suggests in ―Exchange,‖ the greatest change comes about when profit is low, the interaction will continue until the ―costs of avoiding interaction‖ and the rewards from the interaction diminish. At that point, practical equilibrium is broken and frequency of interaction will be reduced or halted altogether. In the case of our example, a natural end to the interaction comes at the end of the semester.

When the value of what a member of a group receives in terms of rewards is comparable to what he puts into the group, Homans terms this distributive justice ( Social

234). Distributive justice, in a sense, is the feeling of equity within a group, the idea that individuals get what they deserve. Even though the contributions of one member may be more valuable than that of another, the group has reached a level of practical equilibrium, meaning that those members with low social approval still contribute enough to the group that equity is maintained. The only example of distributive justice available in our example comes in the social reward of grades given by Professor. The expectation of the

11

Classmates is that Student will receive an A for his consistent good work and that Other will receive a lower grade because of his consistent inadequacy to correctly handle the requirements of the class. Because ―what he gives may be a cost to him, just as what he gets may be a reward‖ and because ―the value of what a group member receives from other members should be proportional to his investments,‖ those group members with low social approval may contribute at a greater frequency than those with a high social approval for the purpose of maintaining practical equilibrium and distributive justice

(Homans, ―Exchange‖ 606;

Social 237). In our example, however, an increased frequency of Other‘s deviant behavior results in more negatives than positives, but he may add other behaviors, such as bringing cookies to class, to offset the low social approval from Classmates.

Homans talks of authority in terms of the ability to exert influence over multiple group members comparable to exerting influence over an individual within the group.

Furthermore, authority in terms of social exchange refers to that authority which has been earned as opposed to that which is acquired by appointment or inheritance; therefore, ―In earning esteem men also earn authority‖ (Homans,

Social 286). Because Other has low authority among classmates, his suggestion to form a study group is met with skepticism about the benefits. Student, however, easily convinces Classmates to form a study group even though the group is initially suggested by Other. Because of the high levels of esteem and sentiment Student has earned, Classmates also accept his authority in the suggestion to participate even to the point that if he decides on a different time and place than Other wants, his desires are heeded. In earning esteem, sentiment, and authority through his efforts and abilities in the class, Student becomes a leader within the group.

12

Homans points out that leaders, those who hold earned authority, can sometimes be disliked by their followers, but the several causes of this dislike do not diminish the fact that the followers find their association with group leaders rewarding, often through advice given by the leader.

Equality within a group, especially concerning the leader, may be difficult to determine since ―The cost and the value of what [a group member] gives and of what he gets vary with the quantity of what he gives and gets‖ (Homans, ―Exchange‖ 606). Also, individuals may perceive the value of specific rewards differently from their fellow group members, creating a need for different or more frequent rewards in order to maintain practical equilibrium within the group. If one group member is perceived to have received greater rewards than he is due, Homans‘s principles suggest that others will maneuver to rectify the situation. Members of a group often perceive leaders to have obtained greater rewards than the majority; however, those leaders are also perceived to deserve those rewards. Another observation about those with whom group members prefer to interact also relates to equality: ―[T]he tendency for a man to interact with his

‗betters‘ may be especially strong when he is not just a little inferior to them but definitely a good deal inferior‖ (Homans, Social 334-35). Therefore, interaction within a group takes place most frequently not only with those a member is equal to and likes but also with those who are perceived to be superior (334). While equality in the exchange is maintained through distributive justice, esteem, authority, and other rewards, those group members whose esteem is lower than the majority of the group are under pressure to associate with those who are of higher esteem, while those of higher esteem are under no such constraint.

13

An invitation by Professor for the group to join him at his home one evening is accepted by Student and Other as well as a number of Classmates. While Student sees this as a reward, Other considers it a requirement, emphasizing again Homans‘s idea that

―[f]or a person engaged in exchange, what he gives may be a cost to him, just as what he gets may be a reward‖ (―Exchange‖ 606). For Student, the opportunity to socialize with

Professor outside the classroom allows for topics of discussion not otherwise available due to the time and subject constraints of the classroom and, because other faculty members will be present, allows Student to meet those who could influence future internship and teaching positions. Other, because he is aware of his status in the class, feels he must attend so as not to offend Professor. Each individual was invited to the same event in the same way, but the value of that socialization is different for each.

Social exchange theory has been extensively studied and utilized in a wide array of circumstances where other theories that do not provide as clear a picture of the dynamics involved in small group relationships, for, as explained by Robert Burgess and

Ted Huston in Social Exchange in Developing Relationships (foreword written by

Homans), ―the developmental course of particular relationships cannot be fully understood by recourse either to individual psychology or to the social system‖ (4). They add the caveat that they do ―not wish to imply that all features of relationships are readily interpretable by exchange theory, or that close relationships in contemporary society are necessarily sustained by the kind of affection based on exchange‖ (24). However, social exchange theory presents unique insight into relationships which might otherwise lack explanation or which might produce false explanations based on misguided assumptions about the nature of those relationships.

14

Two concepts which are particularly useful for considering relationships in literature are comparison level and comparison level for alternatives delineated by

George Levinger in ―A Social Exchange View on the Dissolution of Pair Relationships.‖

The comparison level ―refers to the average value of all outcomes one has experienced in a comparable situation‖ and comparison level for alternatives ―is the level of outcomes expected in one‘s best currently available alternative to the present relationship‖ (171).

Homans includes the pinnacle of the comparison level concept when he states, ―If in the past the occurrence of a particular stimulus-situation has been the occasion on which a man‘s activity has been rewarded, then the more similar the present stimulus-situation is to the past one, the more likely he is to emit the activity, or some similar activity now‖

( Social 53). Levinger exploits these concepts for use with his studies of paired groups

(spousal relationships and homogeneous friendship pairs); however, the ideas on comparison easily extend to relationships in groups greater than two. Each individual within a group, therefore, constantly reevaluates the relationships within that group based on previous life experiences and on possible alternative relationships outside the group or within another group to determine what behaviors to exhibit. When the comparison level of the present group is viewed negatively and the comparison level for alternatives is viewed positively, the individual will abandon the relationships within the current group in favor of more satisfying group relations.

The advantage of considering the relationships in a fictional text, as opposed to studying a group of living individuals, is that the text is static; the relationships in the text never change—they may change in the progression of the story but will always remain the same at a single point within the text. Being removed from the text in this distance in

time, we are able to look at snapshots of those relationships. Since looking at a text is

15 looking at relationships that are set, any change in the relationships has already come, or is documented in its progress, and lacks only the analysis of its cause.

The Range of Application

Within a mimetic context, applications of feminism, Marxism, and psychoanalysis provide a plethora of rich insights into literature that would not otherwise be available, and in the same way, social exchange theory, when used as a critical tool, gives a greater understanding to character interactions and motives. Examining character relationships, motives, and actions in the works of Alfonsi, Shakespeare, Joyce, Tyler, and Hornby provides strong examples of how Homans‘s theory operates with literature in a wide array of time periods and genres.

Each of these authors supplies a unique canvas, revealing different aspects of how social exchange theory maybe employed as a tool for literary analysis. Alfonsi‘s

Disciplina Clericalis allows us not only to see that Homans‘s theory is effective when applied to children‘s literature, but also provides insight into the workings of the teacherpupil relationship during the Middle Ages. With As You Like It, Shakespeare provides a dramatic work to use as a basis for the application of social exchange theory and, as it is well researched, allows a comparison to other interpretations of the actions of the characters Jacques and Touchstone. Joyce‘s Dubliners , an early modernist text, also carries the weight of extensive research and documentation from previous critics but contains the short stories of ―Little Cloud‖ and ―Counterparts,‖ each of which has its particular small group interactions (a homogenous friendship and an employee-employer relationship respectively) available for analysis with Homans‘s theory. Both Tyler and

Hornby are contemporary novelists but have widely varied styles. Tyler‘s Ladder of

16

Years revolves around the concept of the traditional nuclear family while the relationships in Hornby‘s

A Long Way Down involve strangers brought together under unusual circumstances, allowing a comparison of two different types of contemporary novels and extending the range of social exchange theory as a literary tool.

Homans states, ―When I speak of exchange I mean a situation in which the actions of one person provide the rewards or punishments for the actions of another person and vice versa‖ (Foreword xviii). Behavior as social exchange is prevalent in fiction, for in the creation of these works and characters, humans are the source, and fiction, therefore, naturally duplicates life. Furthermore, the more realistic or lifelike a piece of fiction, the more easily a mimetic form of theoretical criticism, such as social exchange theory, can be applied, and because some of the literature analyzed in this thesis is more mimetic than others, social exchange theory applies more readily to some works than others. Since fictional characters, however, originate from within the human psyche, even those works which do not attempt to duplicate reality are legitimately subject to analysis using theoretical criticism within a mimetic context.

CHAPTER II

RELATIONSHIPS IN ALFONSI‘S DISCIPLINA CLERICALIS

If you look at the moon, I was told in my childhood, you can see a man, The Man in the Moon. Likewise, someone—I don‘t recall who—taught me that when you look at the moon, you can see St. George forever slaying the dragon. On a recent trip to visit relatives, I sang a great-nephew to sleep using a song passed down from generation to generation, sung to us by our parents and grandparents, and an older niece asked in shock, ―How do you know that song?‖ Children‘s songs, tales, and stories are passed along through generations, whether or not within a family, in a multitude of ways. One significant artifact in this passing is Petrus Alfonsi‘s Disciplina Clericalis, which acts as a clearing house for medieval children‘s literature by collecting from other cultures and providing source material to future generations. When viewed through the lens of

Homans‘s social exchange theory, the

Disciplina Clericalis provides insight into medieval relationships between parents and children, teachers and students, and other various individuals, and the use of social exchange theory reveals particular viewpoints and attitudes, especially involving moral expectations, concerning those interpersonal relationships.

Significance of the Disciplina Clericalis

The importance of Alfonsi‘s Disciplina Clericalis cannot be overstated, for not only is this work an important collection of ancient literature, but it acts as source material for children‘s literature far into the future, as well as for other medieval works

17

18 including Geoffrey Chaucer‘s

Canterbury Tales . Alfonsi gives credit to source material, stating ―I put together this book, partly from the sayings of wise men and their advice, partly from the Arab proverbs, counsels, fables and poems, and partly from bird and animal similes‖ (104). Alfonsi references Aristotle, Plato, Socrates, Enoch, Balaam,

Solomon, and others, while settings or sources of the stories include Spain, Mecca,

Rome, and Egypt. To call the Disciplina Clericalis anything less than eclectic minimizes the width of material the author uses. As an example of the sources from which Alfonsi gathers his material (as well as illustrating the acceptable use of others‘ works in that period), Eberhard Hermes points to the Alexander legend which ―is found not only in collections of Latin exempla, but also in the Qur‘an, the Arabian Nights, and the Talmud‖

(Alfonsi 42). The characters involved in the stories run the full gamut of society: hermits, tailors, kings, philosophers, thieves, servants, and, of course, animals. The didactic nature of the stories seems the only constant thread holding the work together to accomplish the goal, as Alfonsi states, ―that readers and hearers should have both the desire and opportunity for learning‖ (104).

The frame tradition of Arabic storytellers used in the Disciplina Clericalis indicates the level of influence Alfonsi had, and still has, on western writing. Katherine

Gittes states that Spain was the ―most important bridgehead for the dissemination of

Arabic culture‖ and that Alfonsi‘s work was the ―first European frame narrative of importance‖ (244). Not only did Chaucer use this framing tradition in his

Canterbury

Tales , but this method of storytelling is used in contemporary literature and film as seen in Rob Reiner‘s 1986 movie Stand by Me , based on Stephen King‘s novella, The Body . In this film adaptation, an adult writer, Gordie LaChance, sits in his car reflecting on the

19 death of a childhood friend and tells a story (the bulk of the movie) of their younger days.

Chaucer, according to Gittes, mentions Alfonsi five times in the text of Canterbury Tales and Chaucer quotes Alfonsi in ―The Tale of Sir Thomas and Melibee‖ (244). Alfonsi‘s version reads, ―Another has said: ‗Advice that is kept in secret is imprisoned, as it were, and you are its keeper, but advice that has been made plain holds you in its thrall‘‖ (109).

The problems with multiple translations moving Alfonsi‘s work to English, as well as the developmental changes in English over time, are likely the cause of the variances in

Chaucer‘s version of the statement: ―The book saith, ‗Whil thou kepist thi cousail in thin herte, thou kepest it in thi prisoun, and whan thou bywreyest thi couseil to any wight, he holdeth the in his snare‘‖ (108). Alfonsi‘s form is even duplicated by Chaucer, as both men quote an authoritative source to add weight to the saying. Alfonsi uses ―another‖ philosopher while Chaucer‘s storyteller quotes from ―The book,‖ recalling the more recent false adage, ―If it‘s in print, it must be true.‖ Despite differences in the two quotations, the clear reference to and quotation of Alfonsi by a great and influential author such as Chaucer is a significant indicator of the importance of the Disciplina

Clericalis .

As the Disciplina Clericalis exhibits a wide range of material, likewise, Alfonsi himself came from a diverse background. Hermes states that Alfonsi was not merely a

Spanish Jew converted to Christianity who studied as a doctor, but also was an ―Islamic scholar [and] a Rabbi brought up in the traditions of Jewish religious learning, who later, in the year 1106, converted to the Catholic faith‖ (Alfonsi 36). Alfonsi‘s background and education provided him with the resources to undertake the collection found in the

Disciplina Clericalis .

Medieval Children‘s Literature

Gillian Adams‘s ―Medieval Children‘s Literature: Its Possibility and Actuality,‖

20 speaks to the question of whether or not children‘s literature existed in the medieval period and promotes Alfonsi‘s

Disciplina Clericalis as an example of children‘s literature in that time. Adams states:

Written in a very simple Latin at a time when the language often reflected

Ciceronian splendors, this collection of stories primarily from Semitic and

Arab sources, is, on the evidence of Alfonsi‘s ornate preface and an addressee in the text (―a little boy like you‖), especially intended for young students. (―Children‘s‖ 14)

This and further statements emphasize the point that the didactic literature of the time, with a simplification of language and lesson, is medieval children‘s literature. Adams counters ―the romantic notion . . . that didactic works do not count, are not truly

‗literature‘‖ by pointing to the like nature of and explicit lessons from masters such as

Dante and Chaucer (6). In ―A Medieval Storybook: The Urban(e) Tales of Petrus

Alfonsi,‖ Adams again takes up the question of children‘s literature in the medieval ages, looking specifically at Alfonsi‘s work. Adams points to four reasons that the Disciplina

Clericalis should be considered children‘s literature: ―the author‘s express purpose in writing it, the brevity of the text, the simplicity of its language, and the nature of the addressee with the text, clearly a student, often a son . . .‖ (8). While some critics may still deny a place for children‘s literature in medieval times, the strongest evidence that the intended audience is children is the text itself. As Adams indicates, the ―nature of the addressee‖ is either a child or pupil being instructed by a parent or teacher. The first three

21 of Alfonsi‘s tales are Enoch teaching his son, Socrates his followers, and Balaam also his son. The Disciplina Clericalis is medieval children‘s literature.

Application of Social Exchange Theory

In considering Alfonsi‘s work, Homans‘s social exchange theory provides insight into medieval relationships when applied to Disciplina Clericalis, particularly concerning the teacher-pupil and parent-child exchanges. The exchanges that Alfonsi presents to readers reach most aspects of life, including relationships with parents, children, superiors, underlings, friends, mentors, nature, and deities. Using social exchange theory, we can extrapolate information about medieval relationships by applying the theory to the various interpersonal exchanges in the Disciplina Clericalis . Alfonsi demonstrates prescience, unconsciously or at least seemingly, of social exchange theory when he writes of Socrates, who says, ―be not led astray by [hypocrisy] and deprived of the reward for your exertions‖ (105). Socrates or Alfonsi or the original author of this particular story was already aware that relationships, in this case a man‘s relationship with his god, were a matter of cost, ―exertions,‖ and ―reward.‖ Homans warns that we, as humans, already tend to think of behavior as exchange, and this idea, therefore, is ―one of the oldest theories of social behavior‖ (―Exchange‖ 587). Alfonsi supplies a rich trove of material for exploration and analysis, including friendships, mother-daughter relationships, and teacher-pupil relationships.

In the several categories of relationships explored within the Disciplina

Clericalis , friendship takes an early and important position, as Balaam states, ―My son, do not think that one friend is too few and do not imagine that a thousand friends is too many‖ (Alfonsi 105). Within this conversation the tale of another father teaching his son

22 of friendship ensues. In the tale, the son puts his friends to a test, but they fail. Homans‘s theory suggests that their perceived cost of continuing that friendship was too high when the son asks them to help him bury a murdered man. In this case the cost of remaining friends with the son was to become complicit in the murder, but for the friends of the son, the minimal profit (no reward to offset the cost) creates a lack of equilibrium which upsets the cohesiveness of the group, demanding the son‘s removal. One former friend states, ―You shall never from this day forward enter my house‖ (Alfonsi 106). Homans suggests the positive aspect of the theory when he says, ―behavior changes less as profit, that is, reward less cost, tends to a maximum;‖ however, we see the inverse of Homan‘s principle in this instance, wherein changes in the relationships increase when profit tends toward the negative (―Exchange‖ 606).

In the story of ―The Perfect Friend,‖ two merchants (friends) were in love with the same woman, each man‘s love unbeknownst to the other, and when the one, who had planned to marry her, found that the other was lovesick for her, he let the lovesick friend marry her and gave all that he had planned to give her as his wife to his friend instead.

Until this point in the relationship between the two men, equilibrium exists from their previous communication in which they ―used messengers to inform each other of necessary business,‖ but the profit for the married merchant increases by gaining a wife and the first merchant‘s gifts (Alfonsi 107). Homans hypothesizes that each member of a group ―tries to see to it that no one in his group makes more profit than he does‖

(―Exchange‖ 606). In this case the married merchant later discovers his friend is destitute and about to be put to death for a murder and attempts to take his place. While the act of having himself put to death may seem counterintuitive as a reward, we must be aware

that rewards can come in many forms, such as a reputation as a self-sacrificing friend.

23

The actual killer eventually confesses to the crime and both merchants are set free; whereupon the married merchant gives the friend half of all he owns, fulfilling Homans‘s requirement that the ―process of influence tends to work out at equilibrium to a balance in the exchanges‖ (Alfonsi 107; Homans, ―Exchange‖ 606). Homans‘s theory reveals, in

Alfonsi‘s writings on friendship, several important points, including behavior as exchange, increased change in behavior that comes with minimized (or negative) profit, the attempt to increase personal profit, and the tendency toward equilibrium.

In the midst of his writings concerning evil women, Alfonsi presents a picture of the relationships between mothers and daughters in ―The Linen Sheet‖ and ―The Sword.‖

Both stories have similar plots wherein a husband goes on a trip and a mother assists her daughter in seeing her child‘s illicit lover, but the husband returns early and the mother finds a way to deceive the husband (121-22). The mother-daughter relationships we see are already in equilibrium, but the daughter uses the relationship to gain a liaison with a lover, maximizing her profit. By hiding her daughter‘s lover, however, the mother increases in profit; whether that profit is control over the relationship, her daughter‘s gratitude, or something less apparent, is never revealed. Looking past the obvious patriarchal leanings of these tales, the most important finding from this section is the ongoing negotiation between the pupil and teacher.

The pupil in Alfonsi‘s collection requests of his teacher any story ―concerning the guile‖ of women so he can increase his learning (119). In doing this, the pupil shows a desire to profit from the relationship. The teacher, however, is reluctant as seen in his expansive explanation that if naïve people read his stories, they will think he is as

immoral as the women about whom he writes. The teacher, in hesitating, shows that he

24 believes he would pay a high cost in continuing his relationship with the student in this particular instance, and that such a cost would effectively negate any profit he might normally gain through his teaching. The student is unwilling to forgo this vein of teaching and points out others who have received accolades or become famous for their writings on the topic, stating ―If you for our useful instruction write in this same way of women, so will you too not receive blame but rather a crown of glory‖ (Alfonsi 120).

Suddenly, the teacher has the possibility to realize more profit through continuing the instruction, making the possibility of assumptions about his character a cost worth paying. The student, requesting more teaching on the same subject, offers what will be a cost to him and profit to the teacher, showing an actual bargain using behavior as the substance of the exchange: ―But I would still wish you would tell me something more about their tricks, if it is no trouble to you, for the more you tell me, the more I will become dedicated to your service‖ (122). The student presents the first part of the exchange, asking the teacher to pay a cost and tell ―something more about their tricks.‖

He attempts to minimize the perceived cost to the teacher by using the phrase ―if it is no trouble‖ and offers the second half of the transaction, the profit for the teacher, to

―become dedicated to [the teacher‘s] service.‖ Instruction is exchanged for dedication.

More insight into the negotiation between the teacher and the pupil is found after

―The King and His Story-Teller‖ when the student tells his teacher, ―The story-teller did not love his king as much as you love me, because he wanted to take advantage of the king . . .‖ (123). The affection the student receives from his teacher is counted as reward along with the instruction the student desires. Though previously suggesting fame and

offering dedication, the student also requests the profit of learning with only his own

25 increase: ―But if you have laid up anything of this type gained from the sages in the library of your spirit, I beg you tell me your pupil, and I will commend it to my faithful memory‖ (130).

In one instance, the same ongoing negotiation between the teacher and pupil is portrayed between father and son when the son asks his father for a story ―that posterity may gain something useful,‖ showing that the learner in these stories is not completely selfish (Alfonsi 136). In a reversal of the parent-child or student-teacher roles, the father requests a story of his son and says, ―Such a story will be a joy and delight to heart and soul‖ (138). This request appears to be a large increase in profit both for the father and the son as the father gains happiness in knowing that his son is duplicating his method of teaching through storytelling, and the son gains experience in teaching with an experienced guide, his father, as well as the boost in confidence his father‘s exuberance likely gives him.

We gain, in the relationships explored through Homans‘s social exchange theory, some insight into medieval thinking. A friend is one who will sacrifice anything, even his own life, for another, which statement is reminiscent of Jesus‘s saying, ―Greater love has no one than this, that he lay down his life for his friend‖ (John 15.13). We find that tales of evil mothers-in-law are nothing new but come to understand that, at least in someone‘s view, a mother values her relationship with her daughter over all else. We learn that whatever arrangement placed the pupil with his instructor, the bargain was an ongoing negotiation, in which each sought, consciously or not, the greater profit in the relationship. Homans‘s theory has done its work. While many of the relationships in the

26

Disciplina Clericalis can be viewed without a particular scope to focus the reader, using social exchange theory as a lens through which to interpret this text allows a deeper understanding of what Alfonsi values and portrays in his work, as well as the broader understanding of the medieval mind.

CHAPTER III

MOTIVE IN THE ATTITUDES, ACTIONS, AND ARGUMENTS

OF SHAKESPEARE‘S TOUCHSTONE AND JAQUES

Cinema fans are seldom surprised to find some favorite old movie remade into a newer version, colorized or starring the latest popular actor or actress. For theater lovers, each iteration of a play with new directors or actors allows for multiple comparisons with previous performances. Often books are adapted to stage or screen, some more successfully than others, and Shakespeare does this in his adaptation of Thomas Lodge‘s

Rosalynde or, Euphues’ Golden Legacy

into the play As You Like It . Edward Baldwin states, ―When Shakespeare wrote ‗As You Like It‘ he did precisely what so many dramatists of to-day are blamed for doing, that is, he dramatized a well-known novel‖

(xviii). Baldwin also points out that Lodge‘s tale comes from an older work often attributed to Chaucer, ―The Tale of Gamelyn‖ (ix). Shakespeare‘s changes to Lodge‘s tale include reducing the violence (elimination of the deaths during the wrestling match) and adding characters. Anne Barton says that Rosalynde has ―no equivalent to

Shakespeare‘s Jaques, or to Touchstone,‖ two characters who comment philosophically throughout the course of the play about a wide range of topics: the nature of humanity, love, country living (365). Edward Thron suggests the importance of Jaques and

Touchstone when he states, ―The individuality of Shakespeare‘s play arises not from what he borrows but from what he adds to the basic structure of his source, Lodge‘s

Rosalynde

‖ and goes on to say, referring to the character additions of Jaques and

27

Touchstone, that ―It is impossible to discuss one fool without the other‖ (12; 66). An

28 analysis of As You Like It using Homans‘s social exchange theory shows how

Shakespeare uses behavior as a medium of exchange in his work, and this analysis allows better insight into the characters unique to Shakespeare‘s play: Jaques, who uses wit as a scourge, and Touchstone, whose comments lighten the mood of the play and the other characters.

Behavior as Exchange in Shakespeare‘s Work

One behavior often used in exchange by Shakespearean characters is speech, and several critics consider rhetorical abilities as exchange in Shakespeare‘s plays. In an exploration of feminine speech in

The Winter’s Tale

, Martine van Elk suggests that

Shakespeare‘s use of speech as a commodity reflects the realities of the King James court: ―The play begins by showing the court to be a place where social identity is constructed through public, rhetorical performance‖ (431). This ―rhetorical performance‖ was an important part of the courtiers‘ overall effect, the success of which assists them in moving up the social order. Likewise, Peter Grav, in Shakespeare and the Economic

Imperative , points out that in A Comedy of Errors

, ―the medium of exchange is linguistic and the currency they use is words‖ (49). In As You Like It , Duke Senior references the court negatively, calling it ―painted pomp‖ and ―envious court,‖ yet speech is valued in the Forest of Arden in the same way it was in the previous court (Shakespeare 2.1.3-4).

Of those who accompany him in his exile, Senior states, ―I smile and say, ‗This is no flattery: these are counsellors / That feelingly persuade me what I am‘‖ (2.1.10-11). In the duke‘s first appearance in the play, Shakespeare takes the opportunity to show that speech is as important in the court of the rural as it is in the urban setting.

But speech is only one of several behaviors that serve as mediums of exchange

29 rather than money or goods in Shakespeare‘s work. Grav states that ―Indeed, the conflation of material concerns with spiritual, political and romantic spheres (among others) was practically a mainstay of Shakespearean drama that manifested itself through the trope, metaphor and, on occasion, through plots that dealt directly with the economic relationships between men and women‖ (2). Grav extends this idea in his assertion that in

The Merchant of Venice happiness equals money, but in As You Like It , happiness equals love and marriage (107). Few of the characters in As You Like It have available monetary assets as indicated in the wrestler‘s description of those who follow the banished Duke

Senior; Shakespeare writes that their ―lands and revenues enrich the new Duke‖ (1.1.102-

03). Orlando has the 500 crowns Adam saved against old age, and Celia buys the sheep cote with her jewels. Otherwise, most exchange in the play is that described by Homans when he says, ―Social behavior is an exchange of goods, material goods but also nonmaterial ones, such as the symbols of approval or prestige‖ (―Exchange‖ 606). In bringing court behavior and values to the rustic setting of Arden, Shakespeare, through

Lodge‘s tale, stirs the romance with his comic pen, revealing the intrinsic value of behaviors, especially speech, rather than the typical commodities purchased with money.

Rhetorical Abilities in Jaques and Touchstone

Of the behavioral exchanges in As You Like It , Jaques and Touchstone use speech as a medium or commodity more than any other characters besides, perhaps, Orlando and

Rosalind. In fact, Jaques and Touchstone are valued most, if not exclusively, for their rhetorical abilities. Jaques, whose companionship could depress the happiest soul, is most valuable to Senior when the former is in a melancholic state, for that mood brings out his

philosophical pronouncements. Upon hearing of Jaques‘s lamentation on the death of a

30 deer, Senior says, ―Show me the place. / I love to cope with him in these sullen fits, / for then he‘s full of matter‖ (2.1.66-68). That the duke wishes to ―cope,‖ confer, with Jaques in a ―sullen fit‖ of depression suggests that the duke has in the past found wisdom,

―matter,‖ in Jaques‘s melancholic musings. Jaques, like other members of the court who follow the duke, has no real monetary support, but whereas some have musical or hunting skills, Jaques has speech.

In the case of Touchstone, Celia first addresses him after a discussion with

Rosalind and concludes her comments to her cousin with this: ―[F]or always the dullness of the fool is the whetstone of the wits‖ (1.2.54-55). However, Shakespeare foreshadows the later revelation that Touchstone is as much, or more, a philosopher as a clown in

Celia‘s next line: ―How now, wit, whither wander you?‖ (1.2.56). While some humor is found in Celia‘s reference to Touchstone as ―wit‖ rather than ―fool‖ or ―clown,‖ she aptly marks what the reader will discover later; ―fool‖ is his title, but ―wit‖ is his description.

The audience is not privy to the initial encounter between Jaques and Touchstone but receives a secondhand account as Jaques celebrates the meeting, identifying

Touchstone‘s clothing as more of a disguise than a reflection of the individual, saying

―Motley‘s the only wear‖ (2.7.34). Prior to this statement, Jaques finds rapturous humor in Touchstone‘s ―deep contemplative‖ to the point that he laughs unendingly and goes on to praise fools as wise, showing that Jaques, known for his philosophy and wisdom, finds the same in Touchstone (2.7.31).

While Jaques is referred to as ―full of matter‖ by the duke, Touchstone is often called a fool; however, the reasoning behind Touchstone‘s accompaniment of Rosalind

31 and Celia suggests otherwise. Although Celia asks to be left ―alone to woo him,‖

Rosalind makes the initial suggestion that he come, asking ―Would he not be a comfort to our travel?‖ (Shakespeare 1.3.133; 1.3.131). Although the simplest explanation would suggest that women journeying in that time period would want a male in their presence, two things indicate a different motive. First, Rosalind already plans to carry a ―curtleaxe‖ and ―boar spear,‖ taking the role of a man and defender in their travels (1.3.114-

122). Second, Rosalind‘s suggestion reveals her adept abilities to get others to do her bidding. Dale Priest identifies three characters as manipulators in ― Oratio and Negotium :

Manipulative Modes in As You Like It,

‖ Jaques, Touchstone, and Rosalind, but the greatest of these is Rosalind (273). In Touchstone, not only has Rosalind found a kindred spirit, another manipulator, but she also robs her uncle of, perhaps, the wisest man in his court. Touchstone, like Jaques, is valued for his rhetorical abilities; however,

Touchstone‘s words will comfort the cousins as they travel to Arden.

Exchange Theory and Motive in Shakespeare‘s Characters

Motive and Jaques

Both Jaques and Touchstone are valued for their abilities with words, and their individual speech is part of the cost they pay in exchanges with the various groups.

However, the question remains of why these wise men would choose to follow others into a hard life in the forest. Although Jaques‘s melancholic manner has value for the

Duke Senior, Jaques also enjoys this depressed state. When Amiens finishes a song, a conversation takes place that reveals this attitude in Jaques‘s character:

32

Jaq .

Ami .

Jaques.

Jaq .

More, more, I pritee more.

It will make you melancholy, Monsieur

I thank it. More, I pritee more. I can suck melancholy out of a song, as a weasel sucks eggs.

More, I pritee more.

Ami . My voice is ragged, I know I cannot please you.

Jaq . I do not desire you to please me. I do desire you to sing. (Shakespeare 2.5.9-18)

Amiens fears that his singing will ―make [Jaques] melancholy,‖ but Jaques, counterintuitively, is thankful for the onset of that emotion. Jaques does not want Amiens to please him with singing; Jaques prefers his depressed state. Homans points out that ―For a person engaged in exchange, what he gives may be a cost to him, just as what he gets may be a reward‖ (―Exchange‖ 606). Jaques enjoys the depressed feeling, because from his melancholia comes the rhetorical wit that causes him to be in demand. Even

Shakespeare‘s seven stages of life, given by Jaques, come with a final note of sadness:

―Last scene of all, / . . . Is the childishness, and mere oblivion, / Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans every thing‖ (2.7.163-66). This line, delivered with a tone of near longing by Richard Pasco in the BBC version, clouds Jaques as an even darker figure than his companions knew, and all are silent until the entrance of Orlando with his venerable

Adam. Jaques‘s pronouncements that accompany his personal darkness bring him the rewards he seeks; therefore, because rewarded behavior tends not to change, Jaques, who

is rewarded at every turn for his detached demeanor, will remain in a depressed state

33

(Homans ―Exchange‖ 606).

By the end of the play, Jaques loses against Shakespeare‘s major theme of love and pronounces blessings, of sorts, to each of the couples; however, with each blessing

Jaques becomes incrementally more depressed, the state in which he is most rewarded, finishing with a predictive warning (based on Touchstone‘s earlier plans) that the marriage will not last. He ends with ―So to your pleasures, / I am for other than for dancing measures‖ (5.4.193-94). True to character and social exchange theory, Duke

Senior gives Jaques his reward, desiring him to stay. Robert Bennett states that ―in choosing the sober intellectual and religious life, he is choosing not to participate in the pleasures allied to court and marriage‖ (202). Jaques‘s melancholia does not allow him to be a part of such a grand celebration, but he takes pleasure in his lonely withdrawal, seeking ―to maximize for himself‖ the rewards he gains from such a life (Homans 606).

Besides his infamous melancholia, Jaques also is rewarded with entertainment.

And although entertainment might often be considered a distraction from sad or worrisome situations, Jaques‘s entertainment is intertwined with his depression. His seven ages of life, which he calls ―acts,‖ begin with Shakespeare‘s famous ―All the world‘s a stage,‖ connecting the idea of an entire lifetime with a stage performance

(2.7.139-43). Part of the entertainment reward Jaques receives from his time with the banished duke comes in the form of watching others in the forest for his own amusement.

Touchstone amuses him during their first meeting, and Jaques looks to repeat the encounter. However, when he finds Touchstone about to marry a country girl, he only observes, revealing himself as a last resort to stopping the show of the wedding, which

cannot go forward without someone to give away the bride (3.5.69). Until this point,

34

Jaques is happy to watch the show, with snide quips about the people involved, seemingly the actors in life as well as in the play.

Motive and Touchstone

Touchstone, as opposed to Jaques, finds the joyful side of his rhetorical abilities and even coaxes laughter from his melancholic counterpart upon their initial meeting

(Shakespeare 2.7.12-43). Furthermore, he jokes in the face of exhaustion when he first enters the Forest of Arden with Rosalind and Celia: ―For my part I had rather bear with you than bear you‖ (2.4.11-12). The three of them are hungry and tired, Celia can go no farther, and Touchstone makes a joke. This manner is the true reason Rosalind thinks he will be a ―comfort for their journey,‖ but for what reason does he choose to follow

(1.3.131)? Much like Jaques, Touchstone has personal reasons for going to Arden beyond, as Priest suggests, the ―authentic loyalty between him and the girls‖ (275). As

Jaques requires inner turmoil to reach the height of his major talent, rhetoric, so

Touchstone requires outer hardship to have material worthy of his patter. In court, he was well placed as suggested when he is discovered missing along with the girls: ―My Lord, the roynish clown, at whom so oft / Your grace was wont to laugh, is also missing‖

(2.2.8-9). But court was too easy. Touchstone puts himself in a position of hardship in order to make fun of his own circumstances and begins as soon as the trio reaches Arden:

―Ay, now am I in Arden, the more fool I. When I was at home, I was in a better place, but travellers must be content‖ (2.4.16-18). Not only does Touchstone‘s comment show that his world was made harder by their exodus, but he is ―the more fool‖ for having come to the forest. The obvious interpretation of this statement is that he has made a mistake in

35 coming with Rosalind and Celia, but the coupling of his decision to ―be content‖ and his humorous quips to his companions suggests that ―more‖ refers to the amount of material at hand. His circumstances have decreased, but his ability to use his greatest asset, his wit, has increased.

Touchstone‘s pleasure in his position as someone who ―must be content‖ is obvious in the fact that he plans to marry Audrey, a native of the area. But the joy he takes from his situation comes in his ability to make fun of it, as with his description of life in Arden:

Cor .

And how like you this shepherd‘s life, Master

Touchstone?

Touch . Truly, shepherd in respect of itself, it is

A good life; but in respect that it is a shepherd‘s life, it is naught. In respect that it is solitary, I like it very well; but in respect that it is private, it is a very vild life. Now in respect it is in the fields, it pleaseth me well; but in respect it is not in the court, it is tedious. As it is a spare life (look you) it fits my humor well; but as there is no more plenty in it, it goes against my stomach. Hast any philosophy in thee, shepherd? (Shakespeare 3.2.11-22)

Touchstone has reason to hate the situation; he is removed from court, doesn‘t get enough to eat, and is more isolated than he desires. However, Touchstone precedes each objection with a counter-balance, not only to entertain, but to explain why he chooses to

36 stay. The rough circumstances of ―this shepherd‘s life‖ allows him the freedom to pursue greater uses of his wit as opposed to ―the roynish clown, at whom [Frederick] was wont to laugh‖ (2.2.8-9). Touchstone misses the comforts (and meals) of the court; however, in the pastoral setting, he has found happiness in his philosophies and in his ability to speak and be taken seriously. Furthermore, the residents of the forest, including Jaques, have more respect for him than he has previously received. Homans specifically identifies

―symbols of approval or prestige‖ as mediums of exchange, and not only does Corin address him as ―Master Touchstone‖ in the passage above, but Audrey calls him ―Lord,‖ a title of respect (Homans, ―Exchange‖ 606; Shakespeare 3.3.5). Touchstone has prestige in the Forest of Arden and willingly exchanges the comforts of court for it.

Though limited space does not allow for a complete analysis of the characters in

As You Like It , this peek into the world of the bard suggests that future studies would show extensive use of behavior as social exchange in the works of Shakespeare and other early romance writers, whose insight into human behavior was apt though not labeled.

Jaques and Touchstone approach the use of their rhetorical abilities in diverse ways,

Jaques to cut and reprove and Touchstone to lighten and enlighten. But each uses these abilities as trade goods in order to gain status and acceptance in the Forest of Arden.

CHAPTER IV

UNEQUAL PAIRINGS IN JOYCE‘S ―LITTLE CLOUD‖ AND ―COUNTERPARTS‖

Eveline, at the close of James Joyce‘s story by the same name, discovers that ―It was impossible‖ to break ties of ―duty‖ with her domineering father to join ―Frank, steaming towards Buenos Ayres‖ (40-41). In Joyce‘s exploration of the Irish personality in Dubliners , he often uses seemingly unbalanced or unequal pairings of individuals to create binaries, highlighting different aspects of the characters: the protagonist and her father in ―Eveline,‖ the narrator and priest in ―The Sisters,‖ Chandler and Gallaher in ―A

Little Cloud,‖ Farrington and Alleyne in ―Counterparts,‖ and Mrs. Kearney and her daughter in ―A Mother.‖ In portraying these relationships, Joyce often leaves readers without simple explanations of why both the dominated character, faced with an overbearing partner, and the stronger character, having to support the burden of the weaker, choose to remain in the relationship. In Dubliners

, Homans‘s approach helps us discover why Joyce‘s characters remain in relationships despite an apparent disparity of power. Social exchange theory reveals why Chandler and Gallaher in ―A Little Cloud‖ and Farrington and Alleyne in ―Counterparts‖ continue in what, on the surface, seems unequal pairings, suggesting that each of Joyce‘s characters holds motivations not typically revealed through other readings of the texts.

Because Joyce‘s work hinges on the relationships he explores in Dubliners , social exchange theory is particularly appropriate for an analysis of that work. Carey Mickalites, in ―

Dubliners

' IOU: The Aesthetics of Exchange in ‗After the Race‘ and ‗Two Gallants,‘‖

37

38 states ―Joyce's psychological and narrative economy of exchange has a strong epistemological kinship with Georg Simmel's sociology of exchange, and Simmel's model offers a productive way to synthesize the economic and psychological—or materialist and phenomenological—poles of much recent Joyce criticism‖ (123). Because

Simmel is a predecessor to Homans in terms of sociology and exchange, Homans‘s ideas are applicable to Joyce‘s

Dubliners in the same way as Simmel‘s theories (Homans,

―Exchange‖ 587). Social exchange theory provides insight to Joyce‘s Dubliners, particularly concerning the seemingly unbalanced exchanges between Chandler and

Gallaher in ―A Little Cloud‖ and Farrington and Alleyne in ―Counterparts.‖

Social Exchange in ―A Little Cloud‖

Gallaher, in ―A Little Cloud,‖ is clearly the dominant personality in his relationship with Chandler, first shown by the repeated reference to Chandler as ―little‖ even though he is ―but slightly under average stature‖ (Joyce 70). Likewise, the beginning of ―Counterparts‖ offers an assertion of Alleyne‘s superiority, his ―furious voice [that] called out in a piercing North of Ireland accent: ‗Send Farrington here!‘‖

(86). Marilyn French in ―Missing Pieces in Joyce‘s

Dubliners

‖ couples the two stories, particularly the characters of Chandler and Farrington, as examples of ―sexual desire . . . sublimated into other emotions‖ (456), suggesting a close connection between the two characters as well as the two stories. French goes on to say:

Farrington has similarities and important differences from Chandler; both make them counterparts. Farrington is large, Chandler, small; he is brutal,

Chandler, gentle; he avoids his work, Chandler works assiduously. But both are sexually deprived; both channel sexual frustration into other

39 areas; and both, finally, take out their frustration and rage on their children. (459)

French‘s analysis suggests that only sexual repression is keeping Chandler and Farrington from reaching an unfilled potential; however, they are also repressed in other, more overt, ways than the lack of sexual release: Farrington is consistently berated by Alleyne, an overbearing English employer, and Chandler, whose relationship with his childhood friend seems more in Chandler‘s mind than in truth, is haunted by his lack of success compared to that of the visiting news writer Gallaher. This fantasy relationship is suggested by Chandler‘s thought that Gallaher ―did mix with a rakish set of fellows at the time‖ (Joyce 72). In his thoughts, Chandler does not include himself in Gallaher‘s circle, though previously he thinks, ―It was something to have a friend like that‖ (70). While some form of association links the two men in the past, Chandler sees a much stronger tie than Gallaher.

Gallaher returns none of the respect and admiration given him by Chandler and is, in fact, condescending in his discussion, stating that the Paris cafés are ―Hot stuff! Not for a pious chap like you, Tommy‖ (Joyce 76). Gallaher assumes that, despite his friend‘s interested questions about Paris and the fact that they grew up in the same Dublin neighborhood, Chandler would be unfit to visit such places. Chandler on the other hand rewards Gallaher with approval and the desire for extending the friendship with invitations to his home (79). Gallaher makes excuses not to attend, as he did for not having wished him happy nuptials the year before (78-79). The costs to Chandler in their relationship is especially prominent in their initial exchange of conversation in the bar, once Chandler is able finally to speak:

They clinked glasses and drank the toast.

—I met some of the old gang to-day, said Ignatius Gallaher. O‘Hara seems to be in a bad way. What‘s he doing?