Contents - Palgrave

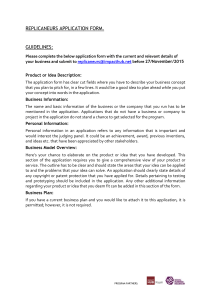

advertisement