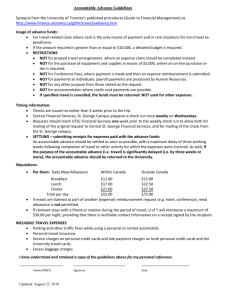

Economic Decision Making

advertisement