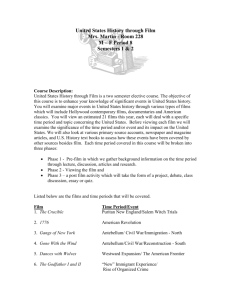

Types of Fictional Films

advertisement