2UV3/2UV3 PEACE ST American Foreign Relations Since 1898

advertisement

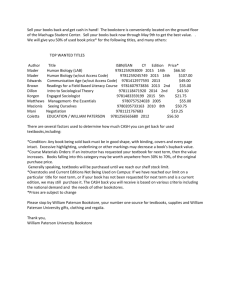

U.S. FOREIGN RELATIONS SINCE 1898 HISTORY/PEACE STUDIES 2UV3 Department of History, McMaster University Fall 2012 Dr. Harish C. Mehta Office location: Chester New Hall Room 401, 4th floor Office Hours: Thursdays 2-3 pm Email: mehtah2@univmail.cis.mcmaster.ca Lectures: Tuesdays, Thursdays (and two special lectures on Friday 7 September, and 26 October) at 11.30 am to 12.20 pm / Burke Science Building/B135 Film shows in class on Fridays (Sept 14, Oct 5 and 12, and Nov 9) Course Description The focus is on the conduct of U.S. diplomacy, the projection of U.S. power and culture overseas during the late-19th and 20th centuries (a period known as the “American Century” because the United States had emerged as an economic and military superpower), and the rise of the American Empire. Students will be introduced not just to traditional diplomatic history, but also to the works of historians who have explained the cultural dimensions of U.S. foreign policy, the role of gender and race in the creation of policy, and the role of personalities. Students will get a “laboratory experience” as they read historical documents. We will also view a series of historical documentary films. By doing so, students will actually engage with the sources, thereby drawing their own conclusions. Students will not just read history, but “do history.” This course will prepare students for the level-four research seminar, History 4JJ3, on selected topics in U.S. foreign relations history. Learning Objectives The aim is to familiarize students not just with the key events, policies, and doctrines in the history of U.S. foreign relations, but also with historical documents, both print and cinematic. Students are encouraged to explore online archival resources such as: • Foreign Relations of the United States. Visit http://history.state.gov/ • U.S. National Archives. Visit http://www.archives.gov/ • Cold War International History Digital Archive. Visit http://www.wilsoncenter.org/digital-archive These resources will enable students to read original documents, and use them in their written assignments. At the end of the course, students will have excellent understanding of U.S. foreign relations history. Required Books American Foreign Relations: A History Since 1895, Vol. 2, Thomas G. Paterson, et al, 7th Edition. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010. ISBN 978-0-54722569-2. 2. American Foreign Relations Since 1898: A Documentary Reader, Jeremi Suri, Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4051-8447-2. 1. 1|Page Research Essay, Tutorial Participation, and Mid-term and Final Examinations Mid-term Exam in class on 25 October consisting of one essay and two short identification questions. • 2,500-word Research Essay based on historical documents, academic books, and journal articles. Do not exceed (or fall short of) the word limit. Essays must be in 12-point type, and double-spaced. Note: A 2% per day penalty will apply to late essays. Weekends count as one day. • Tutorial discussions will be based on documents and essays in Jeremi Suri, American Foreign Relations Since 1898: A Documentary Reader. • Final examination consisting of two essays, and short identification questions. • Mid-term Exam Research Essay Tutorial Participation Final Exam Grading On 25 October Due 15 November TBA 20% 30% 20% 30% Tutorial Participation 1. Attendance is necessary. 2. Participation is based on self-evaluation. Each student will be given a “Participation Evaluation Form,” on which they will evaluate their performance in each tutorial and give themselves a mark out of 10. Students will write a sentence or two on what they contributed. At the end of the tutorial, students will return their evaluation forms to the TA, who will assign a countermark. Discussions will be based on documents and articles in the Documentary Reader. 3. Tutorial topics generally follow topics taught in lecture by one or two weeks, in order to prepare students for discussion. 4. Enthusiastic participation is encouraged. Your comments and analysis are greatly valued. Documentary films On five Fridays, we will view a series of documentary films that are based on historical source material, and historical personalities. The films are intended to provide students with a visual image of U.S. foreign relations history, and serve as background to the readings. They present the cultural and propaganda dimensions of U.S. foreign policy. Rules and Regulations 1. Academic Integrity You are expected to exhibit honesty and use ethical behaviour in all aspects of the learning process. Academic credentials you earn are rooted in principles of honesty and academic integrity. Academic dishonesty is to knowingly act or fail to act in a way that results, or could result in unearned academic credit or advantage. This behaviour can result in serious consequences, e.g. the grade of zero on an assignment, loss of credit with a notation on the transcript (notation reads: “Grade of F assigned for academic dishonesty”), and/or suspension or 2|Page expulsion from the university. It is your responsibility to understand what constitutes academic dishonesty. For information on the various types of academic dishonesty please refer to the Academic Integrity Policy, located at http://www.mcmaster.ca/academicintegrity The following illustrates only three forms of academic dishonesty: 1. Plagiarism, e.g. the submission of work that is not one’s own or for which other credit has been obtained. 2. Improper collaboration in group work. 3. Copying or using unauthorized aids in tests and examinations. 2. Email Communication It is the policy of the Faculty of Humanities that all email communication sent from students to instructors (including TAs), and from students to staff, must originate from the student’s own McMaster University email account. This policy protects confidentiality and confirms the identity of the student. Instructors will delete emails that do not originate from a McMaster email account. 3. Avenue to Learn In this course we will be using Avenue to Learn. Students should be aware that, when they access the electronic components of this course, private information such as first and last names, user names for the McMaster e-mail accounts, and program affiliation may become apparent to all other students in the same course. The available information is dependent on the technology used. Continuation in this course will be deemed consent to this disclosure. If you have any questions or concerns about such disclosure please discuss this with the course instructor. 4. Modifications to Course Outline The instructor and university reserve the right to modify elements of the course during the term. The university may change the dates and deadlines for any or all courses in extreme circumstances. If either type of modification becomes necessary, reasonable notice and communication with the students will be given with explanation and the opportunity to comment on changes. It is the responsibility of the student to check their McMaster email and course websites weekly during the term and to note any changes. 5. Extensions or Accommodations Extensions or other accommodations will be determined by the instructor and will only be considered if supported by appropriate documentation. Absences of less than 5 days may be reported using the McMaster Student Absence Form (MSAF) at www.mcmaster.ca/msaf/ . If you are unable to use the MSAF, you should document the absence with your faculty office. In all cases, it is YOUR responsibility to follow up with the instructor immediately to see if an extension or other accommodation will be granted, and what form it will take. There are NO automatic extensions or accommodations. Guide to the Writing Assignment For writing and formatting style, use the Chicago Manual of Style. Visit the website at: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html Make sure that you use proper citation style for footnotes and bibliography (each has a different style). Both footnotes and bibliography are required. 3|Page The essay must be in 12 point type, double-spaced, and submitted in paper copy in class on the due date. Detailed explanation on how to write history essays will be posted on Avenue, and will also be explained in tutorial. Research Essay A minimum of SIX sources must be used in the essay. You must use at least ONE each of the following sources -- document, journal article, and a scholarly book. (You are welcome to use more than six sources if you wish). You may use the two textbooks, but these two sources do not count among the required books and journal articles. Select the required books from: (a) the book list at the end of each chapter in Paterson and the bibliography at the end of Suri; (b) American Foreign Relations Since 1600, edited by Robert L. Beisner (a comprehensive guide to the literature on American Foreign Relations, which is available in Mills Library under Call Number Z6465 .U5 G84 2003 E183.7. This resource is also available online through the Mills Website. Select the required journal articles from among journals such as Diplomatic History, Journal of Cold War Studies, and other journals. A list of journals will be posted on Avenue. Make sure that you choose the most appropriate books/journal articles. You can also meet a Reference Librarian at Mills, and they will explain how to find appropriate journals. Remember! The essay must have a thesis. The introduction must answer the research question briefly, and formulate a clear argument. You need to take a clear stand on the issue, and explain your position or argument throughout the essay. Make sure that your views/standpoint/arguments are supported by historical evidence (documents, and scholarly books/journal articles). Write the Essay on one of the following questions: 1) Why did the United States military intervene in Cuba and the Philippines in 1898? Analyze President William McKinley’s war message to Congress. How did he justify asking Congress to declare war on Spain. Explain how would you interpret his speech in light of what scholars have since revealed about U.S. motivations in the SpanishAmerican-Cuban-Filipino War? 2) Some historians have praised President Woodrow Wilson for his global vision, his opposition to European power politics, and for giving America a leadership position in the world. Others historians have labeled him an impractical idealist. In light of what scholars have said about Wilson and his legacy, how would you assess his presidency, both at home and abroad? 3) Assess President Theodore Roosevelt’s foreign policy. In your view, was he both a visionary who tried to foster modernization in Latin America, and an expansionist whose gendered and racial views imposed “dollar diplomacy” and U.S. imperialism in Latin America? Which of the two policies were more advantageous to U.S. interests – his expansionism, or his modernization drive? 4) What were the reasons that U.S. foreign policy evolved from “big stick” diplomacy to the Good Neighbor Policy? What was the role of Anti-Imperialist groups in the United States in shaping U.S. foreign policy at this time? 5) What were the key features of U.S. foreign policy during the Interwar Years? Did the United States become isolationist after World War I? 4|Page 6) What were the reasons that the United States dropped the Atomic Bomb on Japan? Should the United States have pursued alternatives to dropping the bomb to end the Second World War? 7) Who was more responsible for the outbreak of the Cold War – the United States or the Soviet Union? Or were they equally responsible? 8) How did European governments and people respond to U.S. cultural exports to Europe during the Cold War? Were U.S. music, dance, and news propaganda examples of “cultural imperialism,” or “empire by invitation?” 9) Was the Korean War predominantly a civil war, or was it a noble “police action” taken by the United States to block the expansion of Soviet-backed Communism? 10) What role did the United States play in the coup in Iran in 1953? What was the impact of the U.S. role in Iran for the Middle East as a whole? 11) Explain when, how, and why did the United States become so closely allied with Israel? Were all U.S. State Department officials and Congressmen unanimous in their support for Israel? 12) Did President Kennedy conduct brilliant diplomacy to defuse the Cuban missile crisis? And, what caused the Cuban missile crisis – U.S. intervention, Soviet imperialism, or both? 13) What caused the failure of the multi-million dollar U.S. development program known as the Alliance for Progress? 14) What caused the failure of U.S. “nation building” strategies in Vietnam? Assess Robert McNamara retrospective claim that the United States “made an error not of values and intentions but of judgment and capabilities” in its intervention in Vietnam. 15) Did the United States lose the war in Vietnam because (a) the antiwar movement, the liberal media, and Washington officials forced the U.S. military to fight a “limited war?” or because (b) U.S. objectives of the war were poorly defined and clashed with Vietnamese nationalism? 16) Did the Nixon administration play a major role in overthrowing the government of Chile in 1973? Explain, and provide evidence. 17) Examine the effects of the “Vietnam Syndrome” in the way that the United States has intervened in several countries since 1975. 18) What are the underlying sources of anti-Americanism in the Middle East? In your answer examine the major U.S. policies and interventions in the Middle East from the 1930s to the present. CLASS AND TUTORIAL SCHEDULE The two textbooks are Paterson and Suri. 6 SEPTEMBER (Thurs) Introduction to the Course Lecture: Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War, and the Open Door in China Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 1, pages 1-29 (“Imperialist Leap”) 7 SEPTEMBER (Fri) Lecture: 1) Major Themes in U.S. Foreign Relations History: American Manifest Destiny and American Exceptionalism; and (2) Primary and Secondary Sources in U.S. History 5|Page 11 SEPTEMBER (Tues) Lecture: Building the Panama Canal, and Restricting Cuba’s Independence Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 2, pages 33-45 (“Managing, Policing, and Extending the Empire”) 13 SEPTEMBER (Thurs) Lecture: The Roosevelt Corollary and Dollar Diplomacy Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 2, pages 45-64 (“Managing, Policing, and Extending the Empire”) 14 SEPTEMBER (Fri) Film to be shown in class: “Savage Acts: Wars, Fairs.” Documentary examining U.S. imperialism, expansionist policies, and wars at the beginning of the 20th Century, with special focus on U.S. annexation of the Philippine Islands and racial attitudes portrayed in the World’s Fairs of 1893, 1901, and 1904. Film uses political cartoons, animation, and excerpts from diaries. 18 SEPTEMBER (Tues) Lecture: From U.S. Neutrality to U.S. Entry in World War One Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 3, pages 70-90 (“War, Peace, and Revolution in the Time of Wilson”) 20 SEPTEMBER (Thurs) Lecture: Woodrow Wilson’s 14 Points, the League Fight, and the Red Scare Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 3, pages 90-106 (“War, Peace, and Revolution in the Time of Wilson”) 25 SEPTEMBER (Tues) Lecture: The Interwar Years, and U.S. Isolationism Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 4, pages 111-139 (“Descending into Europe’s Maelstrom”) TUTORIALS START TODAY Tutorial 1: Readings: Suri, Chapter 1, “War, Imperialism, Anti-Imperialism” 27 SEPTEMBER (Thurs) Lecture: Japan’s Hegemony in China, and the Good Neighbor Policy Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 5, pages 145-172 (“Asia, Latin America, and the Vagaries of Power”) 2 OCTOBER (Tues) Lecture: The Road to World War Two: From U.S. Neutrality to the Attack on Pearl Harbor Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 6, pages 177-190 (“Survival and Spheres: The Allies and the Second World War, 1939- 1945”) Tutorial 2: Reading: Suri, Chapter 2, “The Great War and its Aftermath” 6|Page 4 OCTOBER (Thurs) Lecture: The Diplomacy of World War Two, the Politics of the Second Front, and New Postwar World Order Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 6, pages 190-217 (“Survival and Spheres: The Allies and the Second World War, 1939- 1945”) 5 OCTOBER (Fri) Film to be shown in class: “Prelude to War: World at the Brink” Director Frank Capra, 1942. This is part of a series of films made by the United States Army to indoctrinate U.S. servicemen and explain why the United States was at war and why the men were being sent overseas. The narrator suggests that Americans are fighting for freedom the world over. Enslavement began with Italy, when the people handed over power to Mussolini. It can also be seen in Hitler’s Germany and Tanaka’s Japan. Further comparisons are made between the three countries: all had new armies, uniforms, symbols and slogans. Each system's constitutional law-making bodies gave up their power, and various freedoms of the people were removed. The narrator finishes the film with an emotional appeal to the audience, stating that, after 170 years of freedom, Americans must fight the dictators who would crush it. 9 OCTOBER (Tues) Lecture: The Origins of the Cold War Background Readings: Paterson, Chapter 7, pages 225-250 (“All Embracing Struggle: The Cold War Begins”) Tutorial 3: Reading: Suri, Chapter 3, “The Great Depression, Fascist Fears, and Social Change in America” 11 OCTOBER (Thurs) Lecture: U.S. Foreign Policy Doctrines of “Containment,” and “Rollback” & Cold War Culture Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 7, 250-259 (“All Embracing Struggle: The Cold War Begins”) 12 OCTOBER (Fri) Film to be shown in class: “The Nazis Strike,” Director Frank Capra, 1942. This is part of a series of films made by the United States Army to indoctrinate U.S. servicemen and explain why the United States was at war and why the men were being sent overseas. This is a U.S. army propaganda film record of Germany’s preparations for war, the conquest of Austria and Czechoslovakia, and the attack upon Poland. 16 OCTOBER (Tues) Lecture: U.S. “Police Action:” The Korean War Background Readings: Paterson, Chapter 8, pages 267-275 (“Cold War Prisms”) Tutorial 4: Reading: Suri, Chapter 4, “The Second World War” 18 OCTOBER (Thurs) Lecture: Eisenhower’s Foreign Policy: The Hidden Hand Presidency Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 8, pages 275-310 (“Cold War Prisms”) 23 OCTOBER (Tues) Lecture: The Cuban Missile Crisis & Flashpoint in Berlin Background Readings: Paterson, Chapter 9, pages 328-343 (“Passing the Torch”) Tutorial 5: Reading: Suri, Chapter 5, “The Early Cold War” 7|Page 25 OCTOBER (Thurs) MID-TERM EXAM IN CLASS TODAY 26 OCTOBER (Fri) Lecture: The Origins of the Vietnam Wars Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 9, pages 320-328 and 343-349 (“Passing the Torch”) 30 OCTOBER (Tues) Lecture: Johnson’s War in Vietnam, and Nixon’s “Peace with Honor” Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 9, pages 350-359 (“Passing the Torch”); and Chapter 10, pages 390-398 (“Détente and Disequilibrium”) Tutorial 6: Readings: Suri, Chapter 6, “Rebellions against the Cold War” 1 NOVEMBER (Thurs) Lecture: U.S. Normalization with China, Détente, and Nuclear Arms Reduction Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 10, pages 367-378 and 382-389 (“Détente and Disequilibrium”) 2 NOVEMBER (Fri) Special Class on Writing the Research Essay 6 NOVEMBER (Tues) Lecture: U.S. Interventions in the Middle East, 1952-1979 Background Readings: Paterson, Chapter 8, pages 300-303 (“Cold War Prisms”); Chapter 10, pages 378-382 and 406-411 (“Détente and Disequilibrium”) Tutorial 7: Reading: Suri, Chapter 7, “Détente, Human Rights, and the Continuation of the Cold War” 8 NOVEMBER (Thurs) Lecture: The Foreign Policy of President Carter, and the Vietnam Syndrome Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 10, pages 398-406, and 411-414 (“Détente and Disequilibrium”) 9 NOVEMBER (Fri) Film to be shown in class: “The Atomic Café.” Documentary based on newsreel footage and U.S. government archives of the 1940s and 1950s. Using humor to expose U.S. policy and paranoia, this film focuses on U.S. concern about nuclear war, and on various hypothetical approaches to dealings with nuclear devastation. This is a unique documentary about Cold War hysteria over the Atom Bomb in the United States. 13 NOVEMBER (Tues) Lecture: Who Won the Cold War? Background Readings: Paterson, Chapter 11, pages 421-443 (“A New World Order?”) RESEARCH ESSAY DUE IN LECTURE TODAY Tutorial 8: Readings: Suri, Chapter 8, “The End of the Cold War” 8|Page 15 NOVEMBER (Thurs) Lecture: The Post-Cold War World Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 11, pages 443-463 (“A New World Order?”) 20 NOVEMBER (Tues) Lecture: The End of the American Century? Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 10, pages 385-389 (“Détente and Disequilibrium”); and Chapter 11, pages 463-471 (“A New World Order”) Tutorial 9: Readings: Suri Chapter 9, “After the Cold War” 22 NOVEMBER (Thurs) Lecture: U.S. Invasion of Iraq, and War on Terror Background Reading: Paterson, Chapter 12, pages 479-515 (“Millennial America”) 27 NOVEMBER (Tues) Lecture: American Orientalism: Ways of Seeing Background Reading: Tutorial 10: Readings: Suri, Chapter 10, “The War on Terror” • • 29 NOVEMBER (Thurs) Drawing conclusions about the History of U.S. Foreign Relations Final Exam Prep FINAL EXAM Date to be announced 9|Page END OF SYLLABUS 10 | P a g e