Authority - Yale Law School

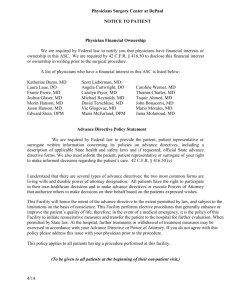

advertisement