Evaluation of the Hand - American College of Emergency Physicians

advertisement

(+)ScottC.Sherman,MD

AssociateProfessorofEmergencyMedicine,Rush

MedicalCollege;AssistantProgramDirector,Cook

CountyEmergencyMedicineResidency;Physician

AssistantResidencyDirector,Chicago,Illinois

AdvancedPracticeProvider

Academy

April14‐18

SanDiego,CA

EvaluationoftheHand:HowtoExaminetheHand

andEvaluatethePatientwithHandProblems

Theabilitytoproperlyexaminethehandisanessential

skillforanyproviderworkingintheED.Patients

frequentlypresentwithhandpain,handinfectionsor

handinjuries.Thespeakerwillreviewthefunctional

anatomyofthehandandwillexplainhowtoperforma

goaldirectedhandexamination.Commonhanddisorders

willalsobediscussed.

Objectives:

Reviewthefunctionalanatomyofthehand.

Describehowtoperformagoaldirected,time

efficienthandexamination.

Listcriticalhigh‐riskhandproblemsthatyoucan’t

affordtomissincludingforeignbodies,highpressure

injectioninjuries,tendonlacerationsanddeepspace

infections.

Date:4/14/2014

Time:3:30PM‐4:00PM

CourseNumber:MO‐13

(+)Nosignificantfinancialrelationshipstodisclose

High-Risk Injuries and Infections

of the Hand

Scott C Sherman, MD

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Rush Medical School

Department of Emergency Medicine

Cook County Hospital (Stroger)

ssherman@ccbh.org

Hand injuries account for up to 15% of all trauma cases seen in the emergency

department1. These injuries are important because the disability that can result disrupts a

patient’s daily life and livelihood. These injuries represent a significant source of

malpractice claims.

Hand Anatomy

A. Surface anatomy: Use the terms volar (palmar), dorsal, radial, and ulnar. The

creases on the volar aspect are named the proximal and distal palmar crease. The

distal palmar crease overlies the mid point of the proximal finger phalanx.

B. Skin: The skin of the volar hand and fingers is fixed to the underlying bone by

fibrous septa. This helps with grip, limits movement, and does not allow

significant swelling. The dorsal hand has looser, thinner skin. This allows a fairly

extensive space for swelling from trauma or infection.

C. Nail: The nail complex consists of the eponychium (cuticle), perionychium (nail

edge), hyponychium (under the tip of the nail), and the nail bed or matrix (under

the nail plate).

Hand Examination

A. Neurologic assessment:

1. Digital nerve: Use two-point discrimination with a paper clip. Normal twopoint discrimination is between 2 and 5 mm at the volar fingertip. Test an

uninjured finger to estimate the patient’s normal ability. Start at 1 cm, and

decrease the distance until two points are no longer felt. Test one digital nerve

at a time by placing both points of the paper clip on the same side of the

fingertip.

1

2. Forearm injuries may result in neurologic deficits in the hand. It is important

to document these at the time of the initial exam.

Radial nerve: Sensory function is assessed at the dorsal web space of the

thumb and index finger. Motor function is tested by assessing extension of

the wrist or fingers.

Ulnar nerve: The sensory function is tested at the volar tip of the small

finger. The ulnar nerve innervates the intrinsic muscles of the hand. Have

the patient spread the digits against resistance. Another reliable test for the

function of this nerve is to have the patient place the ulnar edge of the

hand on the exam table, and then have them attempt to abduct the index

finger against resistance.

Median nerve: Sensory function is assessed at the volar tip of index

finger. Motor strength is best assessed by thumb abduction (have the

patient raise the thumb towards the ceiling while the dorsal hand is flat on

the exam table). This tests the function of the abductor pollicis, which is

reliably innervated by the motor nerve branch of the median nerve.

B. Tendon assessment:

1. With injuries that lacerate or penetrate, it is important to document tendon

function. Excess flexion occurs with an extensor tear, while excess extension

is seen with flexor tendon injuries.

2. Each finger should be examined independently for flexion of the distal

phalanx (profundus tendon) and the whole finger (superficialis tendon).

Testing is performed against resistance. Any weakness or pain might indicate

a partial injury.

3. Open injuries need to be assessed with a bloodless field and direct inspection

of the tendon through a full range of motion. Tendon lacerations are missed in

approximately 1/3 of instances2.

C. Vascular assessment:

1. Injuries to vascular structures usually do not affect perfusion of the hand

because of extensive anastomoses.

2. If initial inspection reveals a dusky or cool finger or hand, prompt intervention

is needed. Capillary refill and pulse oximetry waveforms can give some

indication of blood flow to injured digits.

D. Anesthesia

1. Sensory examination must always precede anesthesia.

2. Wrist block includes:

Radial nerve: Lateral to radial artery and skin wheal on dorsum of hand

Median nerve: Between the flexor carpi radialis and palmaris longus

tendons at wrist crease

Ulnar nerve: Lateral to the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon

3. Digit block options include:

Half ring block: Each side of the base of the digits

Metacarpal block: Between the metacarpal heads all the way to the

palmar aspect of the hand

2

Transthecal block: In the center of the proximal digital crease. Go to

bone, pull back slightly, and then inject. Direct injection into the flexor

tendon sheath.

4. Epinephrine injection into the digits has been considered taboo since the

1950’s. A 2005 study of over 3,000 hand surgeries using the typical

concentrations included with local anesthetics (1:100,000) did not find a

single case of digital ischemia3. Epinephrine, in the proper concentration, is

safe to use in the digit, and is advantageous because it increases duration of

anesthesia and decreases bleeding4-9.

Splints and Dressings

A. Hand position: The best position to splint the hand is the position of function

with the wrist extended 15-30º, the MCP joints flexed 60-90º, and the IP joints

flexed 10-15º. Flexion of the MCP joints is important because the collateral

ligaments are stretched the most in this position (avoiding contracture) and the

joint is most stable. This position is sometimes referred to as the “safe” position.

When the MCP’s are at 90º, the term “intrinsic plus” is used.

B. Universal hand dressing: This dressing is used in inflammatory conditions of the

hand. Unfolded 4x4 gauze is placed between the digits and the hand is wrapped

with an elastic bandage. Holes are cut for the fingers and the wrist is taped in

slight extension. This position allows for the best lymphatic drainage so that

swelling subsides more rapidly.

C. Gutter splint: This splint is useful for phalanx and metacarpal fractures. Ulnar

gutter splint immobilizes the 4th and 5th digits, while the radial gutter is used for

injuries to the 2nd and 3rd digits. The hand is immobilized in the “safe” position.

For the radial gutter, cut out a hole for the thumb. In both splints, remember to

place cotton padding between the digits.

D. Dynamic finger splint: This splint immobilizes the injured digit to the adjacent

uninjured digit and allows for motion at the MCP and PIP joint. This splint is

useful for ligamentous injuries of the digits. Cotton padding should be placed

between the digits.

Hand Fractures

A. Rotational deformities. It is important to detect and correct any rotational

deformities before healing occurs, as later repair is difficult. 5 degrees of

metacarpal shaft rotation can result in 1.5 cm of digital overlap10. Rotational

deformities are detected by having the patient flex the fingers, noting that the nail

plates are parallel and that all the fingers “point” to the same location on the base

of the hand.

3

B. Metacarpals 2 – 5 (index through little finger):

1. Head fractures: Usually due to direct blow, and often comminuted or

crushed. Treatment with hard or bulky splints, and ortho follow-up.

2. Neck fractures: Classic is “boxers” fracture (5th metacarpal neck), which

accounts for 5% of all upper extremity fractures, 10% of hand and wrist

fractures, and 20% of hand fractures11-13. Usually angulated in a volar

direction. Treatment varies for index and middle finger metacarpals,

where anatomic alignment is much more important. Ring and little finger

metacarpals can tolerate more angulation without functional impairment.

Management of boxer’s fractures remains controversial. Recommendation

regarding the degree of angulation acceptable before closed reduction is

deemed necessary varies from 20-70º. Problems with closed reduction

include difficulty in maintaining reduction and little influence of

angulation on functional outcome. If closed reduction is to be attempted,

the most common method involves placing the MCP and PIP joints in 90

degrees of flexion and pushing the digit dorsally, allowing the base of the

proximal phalanx to push the metacarpal head back into proper alignment

(90-90 method). Further treatment recommendations vary widely from an

elastic bandage to functional splinting to plaster splinting14-25.

3. Shaft fractures: Often angulated, sometimes spiral or oblique. The more

proximal the fracture, the more important anatomic reduction becomes.

These should be splinted and referred in a timely fashion.

4. Base fractures: Uncommon, and often interarticular. Can affect the

carpometacarpal function. The base of the little finger MC may present

with a fracture-dislocation, as the fragment is pulled by the attachment of

the extensor carpi ulnaris. Splint and refer.

C. Thumb metacarpal:

1. Base fractures. These are often comminuted and dislocated, as the

abductor pollicis longus tendon pulls the fragments. A single fracture with

this finding is called a “Bennett’s” fracture, while a comminuted fracture

(often “T” or “Y” shaped) is called a “Rolando’s” fracture. These

fractures require fixation (percutaneous wires or ORIF) if they are > 1 mm

displaced26.

4

Rolando’s Fracture

Bennett’s Fracture

D. Phalanx fractures:

1. Tuft fracture: Crush injuries. These are open fractures, if the skin is

disrupted. Antibiotics can be administered, although infection is

uncommon. Treated with a protective dorsal splint.

2. Shaft fracture: Often spiral or oblique, these will frequently require

fixation. Initial reduction will often not be maintained, even with splints or

buddy taping. Rotation is again important to detect.

3. Intra-articular fracture: These may need reduction if significant portions

of the joint are involved. “Mallet” finger fracture occurs with a flexion

force applied to the tip of the extending finger. The force causes an

avulsion of the extensor tendon at the dorsal base of the distal phalanx.

The treatment is splinting in extension for 6 weeks27. If greater than onethird of the joint space is involved, surgical repair may be indicated28.

Bony Mallet Finger

5

Finger Dislocations

A. Interphalangeal joint dislocation

1. The IP joints of the fingers have collateral ligaments and a fibrous volar

plate. Dorsal support is minimal and includes the extensor mechanism and

dorsal capsule. Dislocation commonly injures the ligamentous structures

of the joint.

2. The PIP is much more commonly dislocated—usually dorsal. Volar

dislocations result in injury to the central slip of the extensor tendon and

may result in a boutonniere deformity (see below)29.

3. After a digital nerve block, reduction is achieved with gentle traction.

Irreducible dislocations are unusual, but indicate entrapped soft tissues or

bony fragments that usually must be removed in the operating room30-33.

4. Obtain a radiograph, as tiny fragments of avulsed bone at the joint signify

ligament avulsion.

5. Re-examine the joint post-reduction to check for laxity suggestive of

significant ligamentous injury. If there is maintenance of reduction

through the full ROM, then adequate ligamentous support is assumed.

Wide opening on lateral stress testing suggests injury to both the collateral

ligament and volar plate.

6. Splint the joint in 20-30 degrees of flexion. If the joint is stable postreduction, some advocate early motion with dynamic splinting. Open

injuries need orthopedic consultation for debridement, irrigation,

antibiotics, and close follow-up.

Dorsal PIP Joint Dislocation

B. Metacarpophalangeal joints:

1. The MCP joints have unique anatomy that provides strength and range of

motion. The transverse metacarpal ligament provides support by attaching

the MCP joints to each other (except the thumb). There are also collateral

ligaments, which are supported by the lumbrical muscles. The

arrangement provides the ability to abduct when extended, but not when

flexed.

2. The complex anatomy protects against dislocation, but also leads to a

higher incidence of irreducible dislocations. The most common

dislocations are dorsal, and fall into two broad categories34.

6

3. “Simple” dorsal dislocations have a dramatic appearance clinically, with

the MCP joint held in 60-90 degrees of hyperextension. This dislocation is

usually easily reduced with closed techniques. Reduction is achieved by

further hyperextension of the MCP joint, followed by dorsal pressure at

the base of the proximal phalanx. Longitudinal traction may convert a

simple dislocation into a complex one35. After successful reduction,

immobilize the MCP joint in 60 degrees of flexion36,37.

4. “Complex” dorsal dislocations appear subtle clinically, with the proximal

phalanx nearly parallel to the metacarpal. Other findings include a

palpable metacarpal head on the volar surface with dimpling of the palmar

skin. They are often impossible to reduce with closed techniques due to

the interposition of torn ligaments and the arrangement of ligaments and

lumbrical muscles that actually tighten around the head of the metacarpal

as traction is applied, which prevents reduction.

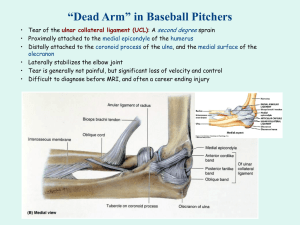

C. Gamekeeper’s thumb: This injury is a sprain or tear of the ulnar collateral

ligament of the thumb MCP joint from forced radial deviation of the thumb (e.g.

falling with a ski pole in the hand). The end result is pain and potential laxity

with gripping. Recovery is slow and surgery may be needed. Initial treatment is

with a thumb spica splint.

Tendon Injuries

A. Extensor tendons:

1. More superficial with thinner skin. Easily lacerated. Tendon injury may be

“open” or “closed”.

2. Open extensor tendon injuries are divided into 8 zones. Zone I is over

the distal IP joint. Zone II includes the middle phalanx. The zones of

extensor tendon injury can be more easily remembered by noting that odd

number zones are over joints, while even numbered zones are over

bones38. Zone VII and VIII involve the carpal bones and distal forearm,

respectively. An emergency physician can repair complete tendon injuries

in zones IV, V, and VI. Other complete extensor tendon ruptures should

be referred to a hand surgeon after suturing the skin and splinting the

hand. Partial open tendon ruptures should be referred, but do not require

repair in most instances39,40.

3. Closed extensor tendon injuries include mallet finger, rupture of the

central slip, and boxer’s knuckle.

a. Mallet finger: Tearing of the insertion of the extensor tendon from the

base of the distal phalanx is known as a “mallet finger”, and is treated

with the joint in extension for 6 weeks. The patient is cautioned not to

remove the splint during this time.

b. Central slip rupture: The central slip of the extensor tendon is

located at the base of the dorsal middle phalanx. At this location, the

tendon splits into three parts, with the central slip attaching to the

bone, and the two lateral parts attaching to the distal phalanx with the

7

lumbrical muscles. When the central slip is ruptured secondary to

contusion, forced flexion, or dislocation of the PIP joint, the extensor

tendon splits and can slip to either side of the joint. In that position,

attempts at extension actually cause some flexion. The end result is a

“Boutonnière deformity”, where the proximal joint is flexed while the

distal joint is hyperextended. The deformity may not be clinically

apparent for 2-3 weeks, but central slip rupture should be expected

when there is extension lag, pain with extension, or pain with resisted

extension. If the injury is suspected, immobilize the PIP joint in full

extension with a dorsal or volar splint with DIP joint unrestricted38.

c. Boxer’s knuckle: Rupture of the extensor hood occurs as a result of

injury to the dorsal aspect of the hand over the MCP joint. In this

scenario, there is disruption of one of the laterally located sagittal

bands that hold the tendon in a central location. The end result is

subluxation of the tendon. These injuries should be splinted and

referred. Splint the hand in only as much extension as is required to

keep the tendon in its proper position41-43.

B. Flexor tendons:

1. Open flexor tendon injuries. There are anatomical “zones” for flexor

tendon injuries, with associated unique problems for healing and repair.

Flexor tendon injuries require repair by a hand surgeon.

a. Zone 1: From the mid portion of the finger to the insertion of the

profundus tendon. Problems with retraction of the proximal part and

the complex pulley system. The FDP emerges from the split FDS in

this zone.

b. Zone 2: From the distal palmar crease to zone 1, where the FDS and

FDP interweave. This area is known as “no man’s land” because the

complex relationships of multiple tendons, sheaths, and pulleys, make

repair difficult. Any scarring leads to long-term functional deficits.

This is the most common area for injury.

c. Zone 3: Mid palm from level of thenar eminence to proximal edge of

flexor sheath. Easier repair with less pulleys and better visualization.

d. Zone 4: Carpal tunnel area, multiple tendons usually involved.

e. Zone 5: Proximal to the carpal tunnel.

2. Closed flexor tendon injury. Jersey finger. This injury is an avulsion of

the flexor digitorum profundus where it inserts on the distal phalanx. The

injury gets its name from the common mechanism of forceful extension

(during active flexion) of the DIP joint, when a football player grabs an

opponent’s jersey with the tip of the finger while that player pulls away44.

8

The index finger is involved in 75% of cases. On examination, there will

be loss of flexion at the DIP joint with normal ROM at the PIP and MCP

joints. Splint the finger with a dorsal splint with the wrist flexed 30

degrees, MCP joint flexed 70 degrees, and the IP joints flexed 30

degrees45. Primary repair is recommended and is best accomplished when

the injury is diagnosed acutely46.

Fingertip Injuries

A. Anatomy: The fingertip is defined as the structures distal to the insertion of the

flexor and extensor tendons on the distal phalanx. It is comprised of the nail,

nailbed, pulp, and distal phalanx. The nailbed is comprised of a germinal and

sterile matrix. The germinal matrix is proximal, ending at the lunula, and accounts

for approximately 90% of nail growth. The sterile matrix makes up the majority

of the nailbed and helps keep the nail tightly affixed to the finger. The proximal

nail fold is termed the eponychium, while the distal junction of the nailbed and

fingertip skin is the hyponychium. The dorsal roof of the proximal nail fold is

responsible for the nail’s shine.

B. Subungual hematoma: In patients with an uncomplicated subungual hematoma

involving >50% of the nail plate, the incidence of a nailbed laceration is 60%47.

However, nail trephination alone (for symptomatic relief), results in a good

cosmetic result without complications no matter how large the hematoma or

whether a fracture is present48-50.

C. Nailbed injury: If the nail is avulsed or lacerated, it is recommended to remove

the nail and repair injuries to the nailbed. The finger is blocked and a tourniquet is

applied. The nailbed is approximated with 6-0 or 7-0 absorbable sutures51.

Following repair, the nail is replaced in the proximal fold and sutured in place for

7-10 days. This practice is felt to help protect the nailbed and eponychium to

allow for growth of the new nail, although it has not been well studied52,53. If the

nail is unavailable, petroleum gauze is used as an alternative.

D. Fingertip amputation: This is a common injury in both adult laborers and

children who accidentally close their finger in a door54. Treatment is

controversial55. Options include skin grafts, replantation, flaps, and conservative

management (secondary intention)56. Prophylactic antibiotics are indicated only in

grossly contaminated wounds57. Conservative treatment with a non-occlusive

(Vaseline gauze) appears to be equally efficacious or better than many surgical

options as confirmed by multiple studies58-68. The authors of these studies cite the

natural regenerative properties of the fingertip, simplicity, decreased cost,

preservation of length, improved cosmesis, low incidence of painful neuromas

and stiffness, and good return of sensation. This technique is employed in children

and adults, and while more common when no bone is exposed, it also has been

successful when the distal phalanx is exposed (even without trimming back the

bone)58,63. Disadvantages include higher incidence of nail deformity and the need

for frequent dressing changes. Replantation is an expensive option requiring a

surgeon skilled in microvascular techniques, but when successful, sensation,

9

length, cosmesis, and ROM are preserved and the incidence of chronic pain is

low69-71. Success rates range from 70-90% and children do especially well. If the

amputation is proximal to the lunula, this is the only procedure that will preserve

the nail. Because the amputated tip does not possess muscle, the period of

ischemia which allows successful replantation is prolonged (8 hours warm; 30 hrs

cold)57.

Amputation

A. All amputated parts should be considered for replantation. The classic indications

include: amputation between PIPJ and DIPJ; thumb; multiple digits; child;

midpalmar amputation; and wrist or forearm. Success is not only related to

viability, but also the restoration of a functional hand.

B. Care of the stump includes achieving hemostasis first. Point control of a bleeding

vessel with a pressure dressing is usually the initial method. Proximal tourniquets

are discouraged unless being used for temporary control or in a patient with lifethreatening bleeding. Use for greater than 3 hours may lead to irreversible

ischemia. Blind ligation or clamping may lead to unnecessary damage to the

nerves or vessels72.

C. Care of the amputated part involves gentle cleansing if heavily contaminated,

wrapping in moist gauze, and storage in a sealed plastic bag. The bag is then

placed into another bag filled with ice water. Properly maintained digits have

about 12 hours of viability.

D. Prophylactic antibiotics and tetanus are indicated.

E. It should always be emphasized the replanted digit will never function normally,

and will likely have some sensory problems, as well as chronic stiffness and

weakness.

10

Bite Wounds

A. Human bites:

1. 35 different bacteria were isolated from the wounds of patients with

human bites, Eikenella corrodens was present in only 17%73. Overall

infection rate is 10%. Amoxicillin clavulanate (Augmentin) is the drug of

choice for human bites and should be administered routinely for wounds

to the hand74. HIV and other blood borne viruses have been transmitted

through human bites and post-exposure prophylaxis should be

considered75-77.

2. In one study, 38% of patients with human bites did not reveal the

mechanism of injury until after they were specifically questioned78.

Always take a thorough history and emphasize the importance of knowing

the true mechanism—higher infection rate.

3. Fight bite injuries (i.e. clenched fist injuries) occur over the dorsum of

the hand at the MCP joint, frequently involving the extensor tendon and

joint space. The injury is sustained following a punch to the mouth (i.e.

tooth). A radiograph should be obtained noting any fracture, evidence of

osteomyelitis, or tooth fragments79. Treatment of an infected fight bite

injury involves hand consultation for surgical debridement, irrigation, and

admission for IV antibiotics. Noninfected bites are managed after adequate

exploration defines the full extent of the injury. Because the wound is

frequently very small (3-5 mm), it should be extended so that all the

potentially injured structures are visualized80. If there is injury to the joint

capsule, tendons, or deep spaces, consultation with a hand surgeon is

obtained for possible admission. If these structures are not involved, the

wound is copiously irrigated, left open to heal via secondary intention, and

oral antibiotics are administered81. Follow-up should be arranged within

24-48 hours.

B. Dog and cat bites:

2. Animal bites account for 1% of all ED visits in the US and the hand and

upper extremity is involved in over half of adult cases73,82,83. Hand bites

have a higher rate of infection than other areas because of avascular

tendons and tendon sheaths that provide a propensity for the spread of

infection.

3. Dog: Potential for significant tissue destruction from large crushing

mechanisms (up to 450 psi). Dog bites account for 80-90% of domestic

animal bites. Obtain radiographs if any concern of bony injury. Superficial

wounds may do well with local care, but deeper wounds need debridement

and antibiotics. Infection rate is between 2-20%.

4. Cat: Deeper penetration than dog bites with the inability to cleanse or

irrigate the depth of the wound. The end result is a higher rate of

infection—30-50%83.

5. Pasteurella multocida is commonly found in both dog and cat bites (75%),

but many species of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria (up to 40 in one study)

11

have been implicated84,85. Augmentin 3-7 days as prophylaxis is the

antibiotic of choice. Doxycycline for penicillin allergic patients.

Hand Infections

A. Paronychia: This is an infection of the lateral soft-tissue fold surrounding the

fingernail. Infection may spread to the eponychium and to the opposite side and

even under the nail in advanced cases. The portal of bacterial entry is frequently

due to trauma (eg, nail biting, manicures, or a hangnail) and is more common with

excessive exposure to moisture (eg, dishwashers)86,87. Use a #11 scalpel along the

nail plate to lift (incise) the lateral nail margin until pus is expressed. If there is no

abscess, dicloxacillin and soaks may be sufficient. Untreated, a paronychia may

spread to become a felon.

B. Felon: This is an infection of the distal pulp space due to minor penetrating

trauma. Because the skin is tightly adherent to the bone, there is little room for

swelling in this area and a great deal of pain is produced. A felon is drained with

an incision over the most prominent portion of the abscess (just like any other

abscess), usually the volar aspect of the finger pad (ie, volar longitudinal

incision). Some authors feel that volar longitudinal incisions will result in painful

scars, but in fact, this incision actually avoids the nerves and circulation, and is

least likely to result in pain and fibrosis88. Alternatively, a unilateral longitudinal

incision may be employed, but the incision must be close to (approx. 5 mm) and

parallel to the nail to avoid the digital nerve86,89. For the unilateral longitudinal

incision, the non-oppositional surface of the involved digit should be used (eg,

ulnar side of index finger). Avoid lengthy and deep incisions, which can cause the

fingertip to become unstable. The fibrous septa that tether the skin to the bone do

not compartmentalize the fingertip, as is commonly believed88. Therefore deep

incisions to cut the septa will only produce an unstable finger pad and not

improve outcome86. Instead of a deep incision, careful blunt dissection is carried

out until the abscess is adequately decompressed. Packing is placed loosely for a

period of 24-48 hours, antibiotics are prescribed, and close follow-up is

arranged90.

C. Flexor Tenosynovitis is a serious infection that can follow minor finger injuries

in which the tendon sheath is penetrated. The tendon sheaths allow spread of the

infection from the DIPJ to the mid palmar crease. In the case of the thumb and

little finger, the sheaths extend to the wrist and communicate in 50-80% of the

population. An infection of this communication is called a “horseshoe abscess”89.

The classic presentation is the “four signs of Kanavel”: Tenderness along the

tendon sheath; Digit held in slight flexion; Pain with forced extension; Diffuse

“sausage like” swelling of the digit. Pain with passive extension is the most

clinically reproducible sign and is best elicited by extending the finger using the

tip of the patient’s fingernail. Early diagnosis and treatment are necessary to

reduce the incidence of adhesion formation within the sheath. Initial treatment

includes splinting, IV antibiotics, and prompt surgical referral. Surgical drainage

is indicated if improvement is not seen in the first 24 hours, and involves

12

proximal and distal tendon exposure with the insertion of a catheter for copious

irrigation90,91.

D. Deep Space Infections represent 5-15% of hand infections92. Without knowledge

of these infections, they may be confused with a more superficial hand abscess or

cellulitis. There are five deep space infections and each one presents with

characteristic findings that will help lead to the diagnosis. All of these infections

require hand consultation for drainage. Web space (collar button abscess):

Significant swelling and pain in the web space and distal palm with the fingers

slightly abducted. Drainage via a longitudinal incision in the web space.

Midpalmar space: Maximal tenderness in the mid palm with loss of the normal

concavity of the palm. Dorsal subaponeurotic space: Located between the

extensor tendons and metacarpals. Dorsal hand swelling that is tender to palpation

with painful finger extension. Thenar space: Tenderness and swelling within the

thenar space with limited movement of the thumb. The thumb is held in abduction

and flexion to increase this potential space90. Hypothenar space: Rare infection

with swelling and tenderness in the hypothenar area.

Thenar Space Infection

Other Conditions

A. Tendonitis: In the hand and wrist, tendonitis occurs where tendons pass through

the flexor and extensor retinaculum. When the first compartment of the extensor

tendons (APL and EPB) is affected, De Quervain’s tenosynovitis

(washerwoman’s sprain) is present. The patient experiences pain over the radial

portion of the wrist, where there may be visible swelling93. There is a marked

increase in pain with the thumb folded into the palm and the wrist ulnar deviated

(Finkelstein test). Treatment is NSAIDs and immobilization with a thumb splint.

Injection with local anesthetic and steroid has a success rate of up to 90% and is

13

attempted when more conservative treatment has failed94. The needle is placed

into the first compartment and directed proximally towards the radial styloid95.

Intersection syndrome (oarsman’s wrist) is inflammation of the tenosynovium of

the second extensor compartment (ECRL and ECRB) where it “intersects” under

the obliquely oriented APL and EPB. Tenderness is elicited 4-6 cm proximal to

Lister’s tubercle. Treatment is similar. Trigger finger (digital flexor

tenosynovitis) occurs when a thickening of the tendon catches at the first annular

pulley. Patients complain of intermittent, painful catching. If the digit is locked,

surgical or percutaneous release is indicated. The most common location is the

thumb and ring finger, but any digit may be affected. Tenderness is elicited in the

distal palm96. Palmar injection into the tendon sheath just distal to the metacarpal

head is curative in 85% of cases97.

B. Compartment syndrome: There are 10 compartments of the hand (4 dorsal

interosseous, 3 palmar interosseous, hypothenar, thenar, and adductor

compartments). The digit also has isolated compartments separate from the

palm98. The most common etiology is an infiltrated IV or arterial line. Other

causes include fractures, high pressure injection injuries, crush injuries, or tight

fitting casts. Pain refractory to medications, pain with passive stretch, and tense

compartments are characteristic findings. When clinical suspicion is present,

consultation with a hand surgeon is recommended for measurement of

compartment pressures and fasciotomy.

C. High pressure injection injuries: Secondary to paint guns, grease guns, or diesel

injectors99. High pressures (up to 10,000 psi) deposit material deep into the

tissues, tendon sheath, and between fascial planes. The kinetic energy produced

by this type of injury is equivalent to a 450 lb weight dropping 25 cm100. The

injury usually occurs due to attempts to clear the “blocked” tool with the nondominant hand. The index finger is most commonly involved, followed by the

middle finger and then palm. The flexor tendon sheath is more commonly

penetrated with injuries at the DIP and PIP flexor creases. Injuries of the thumb

and little finger are problematic because the tendon sheaths are contiguous with

the radial and ulnar bursae, permitting spread to the forearm. Paint and paint

thinner produce a larger inflammatory response than grease, and therefore a

higher rate of amputation. The initial injury often looks benign, so delayed

presentations are most common101. Within hours, the finger starts to become

painful due to vasoconstriction and the inflammatory response. The risk of

amputation is greater when the patient presents > 10 hours after injury. Digital

blocks are contraindicated because they further increase the tissue pressure.

Treatment includes prophylactic antibiotics, tetanus, and surgical decompression

with removal of the foreign material in the operating room102.

Reference List

1. Frazier WH, Miller M, Fox RS, Brand D, Finseth F. Hand injuries: incidence and epidemiology in an

emergency service. JACEP 1978; 7(7):265-268.

2.

Nassab R, Kok K, Constantinides J, Rajaratnam V. The diagnostic accuracy of clinical examination in hand

lacerations. Int J Surg 2007; 5(2):105-108.

14

3.

Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, Sparkes G, Denkler K, Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110

consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J

Hand Surg [Am ] 2005; 30(5):1061-1067.

4.

Sylaidis P, Logan A. Digital blocks with adrenaline. An old dogma refuted. J Hand Surg [Br ] 1998; 23(1):1719.

5. Wilhelmi BJ, Blackwell SJ, Miller JH, Mancoll JS, Dardano T, Tran A et al. Do not use epinephrine in digital

blocks: myth or truth? Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 107(2):393-397.

6. Wilhelmi BJ, Blackwell SJ, Miller J, Mancoll JS, Phillips LG. Epinephrine in digital blocks: revisited. Ann

Plast Surg 1998; 41(4):410-414.

7.

Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: to do or not to do. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;

108(1):114-124.

8. Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective

epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007; 119(1):260-266.

9.

Todd K, Berk WA, Huang R. Effect of body locale and addition of epinephrine on the duration of action of a

local anesthetic agent. Ann Emerg Med 1992; 21(6):723-726.

10.

Lee SG, Jupiter JB. Phalangeal and metacarpal fractures of the hand. Hand Clin 2000; 16(3):323-32, vii.

11.

Hunter JM, Cowen NJ. Fifth metacarpal fractures in a compensation clinic population. A report on one hundred

and thirty-three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970; 52(6):1159-1165.

12.

Hove LM. Fractures of the hand. Distribution and relative incidence. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg

1993; 27(4):317-319.

13.

Abdon P, Muhlow A, Stigsson L, Thorngren KG, Werner CO, Westman L. Subcapital fractures of the fifth

metacarpal bone. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1984; 103(4):231-234.

14. Ford DJ, Ali MS, Steel WM. Fractures of the fifth metacarpal neck: is reduction or immobilisation necessary? J

Hand Surg [Br ] 1989; 14(2):165-167.

15.

Breddam M, Hansen TB. Subcapital fractures of the fourth and fifth metacarpals treated without splinting and

reposition. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1995; 29(3):269-270.

16.

Porter ML, Hodgkinson JP, Hirst P, Wharton MR, Cunliffe M. The boxers' fracture: a prospective study of

functional recovery. Arch Emerg Med 1988; 5(4):212-215.

17.

McKerrell J, Bowen V, Johnston G, Zondervan J. Boxer's fractures--conservative or operative management? J

Trauma 1987; 27(5):486-490.

18. Holst-nielsen F. Subcapital fractures of the four ulnar metacarpal bones. Hand 1976; 8(3):290-293.

19. Bansal R, Craigen MA. Fifth metacarpal neck fractures: is follow-up required? J Hand Surg [Br ] 2007;

32(1):69-73.

20. Arafa M, Haines J, Noble J, Carden D. Immediate mobilization of fractures of the neck of the fifth metacarpal.

Injury 1986; 17(4):277-278.

21.

Lowdon IM. Fractures of the metacarpal neck of the little finger. Injury 1986; 17(3):189-192.

22. Theeuwen GA, Lemmens JA, van Niekerk JL. Conservative treatment of boxer's fracture: a retrospective

analysis. Injury 1991; 22(5):394-396.

15

23.

Kuokkanen HO, Mulari-Keranen SK, Niskanen RO, Haapala JK, Korkala OL. Treatment of subcapital fractures

of the fifth metacarpal bone: a prospective randomised comparison between functional treatment and reposition

and splinting. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1999; 33(3):315-317.

24.

Harding IJ, Parry D, Barrington RL. The use of a moulded metacarpal brace versus neighbour strapping for

fractures of the little finger metacarpal neck. J Hand Surg [Br ] 2001; 26(3):261-263.

25.

Statius Muller MG, Poolman RW, van Hoogstraten MJ, Steller EP. Immediate mobilization gives good results

in boxer's fractures with volar angulation up to 70 degrees: a prospective randomized trial comparing immediate

mobilization with cast immobilization. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2003; 123(10):534-537.

26. Soyer AD. Fractures of the base of the first metacarpal: current treatment options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg

1999; 7(6):403-412.

27.

Lester B, Jeong GK, Perry D, Spero L. A simple effective splinting technique for the mallet finger. Am J Orthop

2000; 29(3):202-206.

28.

Badia A, Riano F. A simple fixation method for unstable bony mallet finger. J Hand Surg [Am ] 2004;

29(6):1051-1055.

29. Peimer CA, Sullivan DJ, Wild DR. Palmar dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg [Am ]

1984; 9A(1):39-48.

30.

Itadera E. Irreducible palmar dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal joint caused by a fracture fragment: a

case report. J Orthop Sci 2003; 8(6):872-874.

31.

Murakami Y. Irreducible dislocation of the distal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg [Br ] 1985; 10(2):231-232.

32.

Inoue G, Maeda N. Irreducible palmar dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal joint of the finger. J Hand

Surg [Am ] 1990; 15(2):301-304.

33. Ostrowski DM, Neimkin RJ. Irreducible palmar dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal joint. A case report.

Orthopedics 1985; 8(1):84-86.

34. Hargarten SW, Hanel DP. Volar metacarpal phalangeal joint dislocation: a rare and often missed injury. Ann

Emerg Med 1992; 21(9):1157-1159.

35.

Stiles BM, Drake DB, Gear AJ, Watkins FH, Edlich RF. Metacarpophalangeal joint dislocation: indications for

open surgical reduction. J Emerg Med 1997; 15(5):669-671.

36.

Stowell JF, Rennie WP. Simultaneous open and closed dislocations of adjacent metacarpophalangeal joints: a

case report. J Emerg Med 2002; 23(4):355-358.

37.

Ferguson DB, Moore G, Hieke KA. Dorsal dislocation of four metacarpophalangeal joints. Ann Emerg Med

1989; 18(2):204-206.

38.

Newport ML. Extensor Tendon Injuries in the Hand. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1997; 5(2):59-66.

39.

Hariharan JS, Diao E, Soejima O, Lotz JC. Partial lacerations of human digital flexor tendons: a biomechanical

analysis. J Hand Surg [Am ] 1997; 22(6):1011-1015.

40.

Wray RC, Jr., Weeks PM. Treatment of partial tendon lacerations. Hand 1980; 12(2):163-166.

41. Perron AD, Brady WJ, Keats TE, Hersh RE. Orthopedic pitfalls in the emergency department: closed tendon

injuries of the hand. Am J Emerg Med 2001; 19(1):76-80.

42. Arai K, Toh S, Nakahara K, Nishikawa S, Harata S. Treatment of soft tissue injuries to the dorsum of the

metacarpophalangeal joint (Boxer's knuckle). J Hand Surg [Br ] 2002; 27(1):90-95.

16

43.

Hame SL, Melone CP, Jr. Boxer's knuckle. Traumatic disruption of the extensor hood. Hand Clin 2000;

16(3):375-80, viii.

44.

Shabat S, Sagiv P, Stern A, Nyska M. Avulsion fracture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon ('Jersey

finger') type III. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002; 122(3):182-183.

45. Simon RR, Sherman SC, Koenigsknecht SJ. Emergency Orthopedics: The Extremities. 5th ed. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 2006.

46. Tuttle HG, Olvey SP, Stern PJ. Tendon avulsion injuries of the distal phalanx. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;

445:157-168.

47.

Simon RR, Wolgin M. Subungual hematoma: association with occult laceration requiring repair. Am J Emerg

Med 1987; 5(4):302-304.

48.

Roser SE, Gellman H. Comparison of nail bed repair versus nail trephination for subungual hematomas in

children. J Hand Surg [Am ] 1999; 24(6):1166-1170.

49. Meek S, White M. Subungual haematomas: is simple trephining enough? J Accid Emerg Med 1998; 15(4):269271.

50. Seaberg DC, Angelos WJ, Paris PM. Treatment of subungual hematomas with nail trephination: a prospective

study. Am J Emerg Med 1991; 9(3):209-210.

51. Brown RE. Acute nail bed injuries. Hand Clin 2002; 18(4):561-575.

52. Boyd R, Libetta C. Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal

Infirmary. Reimplantation of the nail root in fingertip crush injuries in children. Emerg Med J 2002; 19(2):141.

53.

Reichman EF, Simon RR. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 1 ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

54.

Fetter-Zarzeka A, Joseph MM. Hand and fingertip injuries in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2002; 18(5):341345.

55. Martin C, Gonzalez dP. Controversies in the treatment of fingertip amputations. Conservative versus surgical

reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998;(353):63-73.

56. Hart RG, Kleinert HE. Fingertip and nail bed injuries. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1993; 11(3):755-765.

57.

de Alwis W. Fingertip injuries. Emerg Med Australas 2006; 18(3):229-237.

58. Soderberg T, Nystrom A, Hallmans G, Hulten J. Treatment of fingertip amputations with bone exposure. A

comparative study between surgical and conservative treatment methods. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg 1983;

17(2):147-152.

59.

Illingworth CM. Trapped fingers and amputated finger tips in children. J Pediatr Surg 1974; 9(6):853-858.

60. Chow SP, Ho E. Open treatment of fingertip injuries in adults. J Hand Surg [Am ] 1982; 7(5):470-476.

61.

Bossley CJ. Conservative treatment of digit amputations. N Z Med J 1975; 82(553):379-380.

62. Holm A, Zachariae L. Fingertip lesions. An evaluation of conservative treatment versus free skin grafting. Acta

Orthop Scand 1974; 45(3):382-392.

63.

Lamon RP, Cicero JJ, Frascone RJ, Hass WF. Open treatment of fingertip amputations. Ann Emerg Med 1983;

12(6):358-360.

64. Louis DS, Palmer AK, Burney RE. Open treatment of digital tip injuries. JAMA 1980; 244(7):697-698.

17

65.

Mennen U, Wiese A. Fingertip injuries management with semi-occlusive dressing. J Hand Surg [Br ] 1993;

18(4):416-422.

66. Lee LP, Lau PY, Chan CW. A simple and efficient treatment for fingertip injuries. J Hand Surg [Br ] 1995;

20(1):63-71.

67.

Fox JW, Golden GT, Rodeheaver G, Edgerton MT, Edlich RF. Nonoperative management of fingertip pulp

amputation by occlusive dressings. Am J Surg 1977; 133(2):255-256.

68.

Douglas BS. Conservative management of guillotine amputation of the finger in children. Aust Paediatr J 1972;

8(2):86-89.

69. Hattori Y, Doi K, Ikeda K, Estrella EP. A retrospective study of functional outcomes after successful

replantation versus amputation closure for single fingertip amputations. J Hand Surg [Am ] 2006; 31(5):811818.

70.

Hattori Y, Doi K, Sakamoto S, Yamasaki H, Wahegaonkar A, Addosooki A. Fingertip replantation. J Hand

Surg [Am ] 2007; 32(4):548-555.

71.

Dautel G. Fingertip replantation in children. Hand Clin 2000; 16(4):541-546.

72.

Schlenker JD, Koulis CP. Amputations and replantations. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1993; 11(3):739-753.

73.

Brook I. Microbiology and management of human and animal bite wound infections. Prim Care 2003;

30(1):25-39, v.

74. Rittner AV, Fitzpatrick K, Corfield A. Best evidence topic report. Are antibiotics indicated following human

bites? Emerg Med J 2005; 22(9):654.

75. Smoot EC, Choucino CM, Smoot MZ. Assessing risks of human immunodeficiency virus transmission by

human bite injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 117(7):2538-2539.

76. Al Ani SA, Tzafetta K, Meigh RE, Platt AJ. The management of human bites with regard to blood-borne

viruses. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007; 119(7):2347-2348.

77.

Bartholomew CF, Jones AM. Human bites: a rare risk factor for HIV transmission. AIDS 2006; 20(4):631-632.

78. Wallace CG, Robertson CE. Prospective audit of 106 consecutive human bite injuries: the importance of history

taking. Emerg Med J 2005; 22(12):883-884.

79.

Staiano J, Graham K. A tooth in the hand is worth a washout in the operating theater. J Trauma 2007;

62(6):1531-1532.

80. Kelly IP, Cunney RJ, Smyth EG, Colville J. The management of human bite injuries of the hand. Injury 1996;

27(7):481-484.

81.

Perron AD, Miller MD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: fight bite. Am J Emerg Med 2002; 20(2):114117.

82. Overall KL, Love M. Dog bites to humans--demography, epidemiology, injury, and risk. J Am Vet Med Assoc

2001; 218(12):1923-1934.

83. Benson LS, Edwards SL, Schiff AP, Williams CS, Visotsky JL. Dog and cat bites to the hand: treatment and

cost assessment. J Hand Surg [Am ] 2006; 31(3):468-473.

84. Kravetz JD, Federman DG. Cat-associated zoonoses. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(17):1945-1952.

85. Presutti RJ. Prevention and treatment of dog bites. Am Fam Physician 2001; 63(8):1567-1572.

18

86.

Jebson PJ. Infections of the fingertip. Paronychias and felons. Hand Clin 1998; 14(4):547-55, viii.

87.

Roberge RJ, Weinstein D, Thimons MM. Perionychial infections associated with sculptured nails. Am J Emerg

Med 1999; 17(6):581-582.

88.

Kilgore ES, Jr., Brown LG, Newmeyer WL, Graham WP, III, Davis TS. Treatment of felons. Am J Surg 1975;

130(2):194-198.

89. Clark DC. Common acute hand infections. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68(11):2167-2176.

90. Abrams RA, Botte MJ. Hand Infections: Treatment Recommendations for Specific Types. J Am Acad Orthop

Surg 1996; 4(4):219-230.

91. Brown H. Hand infections. Am Fam Physician 1978; 18(3):79-85.

92. Jebson PJ. Deep subfascial space infections. Hand Clin 1998; 14(4):557-66, viii.

93.

Stern PJ. Tendinitis, overuse syndromes, and tendon injuries. Hand Clin 1990; 6(3):467-476.

94.

Thorson E, Szabo RM. Common tendinitis problems in the hand and forearm. Orthop Clin North Am 1992;

23(1):65-74.

95.

Tallia AF, Cardone DA. Diagnostic and therapeutic injection of the wrist and hand region. Am Fam Physician

2003; 67(4):745-750.

96. Watson FM, Jr. Nonarthritic inflammatory problems of the hand and wrist. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1985;

3(2):275-282.

97. Saldana MJ. Trigger digits: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001; 9(4):246-252.

98. Ortiz JA, Jr., Berger RA. Compartment syndrome of the hand and wrist. Hand Clin 1998; 14(3):405-418.

99. Proust AF. Special injuries of the hand. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1993; 11(3):767-779.

100.

Kaufman HD. The clinicopathological correlation of high-pressure injection injuries. Br J Surg 1968;

55(3):214-218.

101.

Schnall SB, Mirzayan R. High-pressure injection injuries to the hand. Hand Clin 1999; 15(2):245-8, viii.

102.

Schoo MJ, Scott FA, Boswick JA, Jr. High-pressure injection injuries of the hand. J Trauma 1980; 20(3):229238.

19