The Boutique Amp Gamble

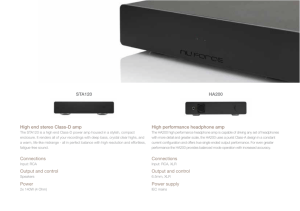

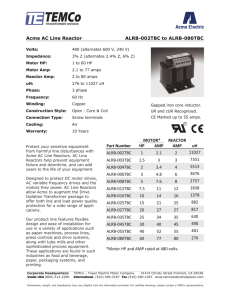

advertisement

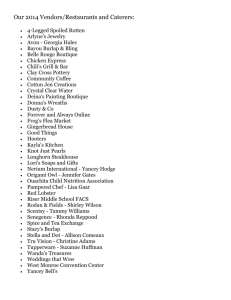

GEAR TREND | BY DAN DALEY The Boutique Amp Gamble n the 1990s, a renaissance of sorts took place in the guitar amplifier business. Several dozen entrepreneurial, technical types began a cottage industry by building guitar amps in basements, garages and storefronts. Driven, self-admittedly, more by a passion for sound than sound economic principles, they came at a time when music instrument manufacturing and retail underwent a huge round of consolidation. Some suggest that the corporatization of the MI landscape helped instigate this grassroots capitalist tornado. To others, it reflected a music industry that itself was on the verge of becoming an independent-driven economy. For whatever reasons, companies with names like Matchless, Top Hat, Naylor, Bogner, Tone King, Guytron and Dr. Z began to vie for the attention of a fast-growing musician base. These entities presented an opportunity to the community of independent music product dealers to carry unique, highmargin guitar products that set them apart from the retail behemoths filled with massproduced products selling at steep discounts. But it was an opportunity that also carried a level of risk. “We would buy these ‘bou- I tique’ amplifiers based on the same sort of passion that the people building them have,” said Dan Tracey, a salesman at World Music in Nashville. “It’s not a product for the weekend-warrior musicians who are looking for lower-priced products. Established ‘name’ musicians will often get endorsement deals and products through them. So, it’s a pretty narrow niche of the customer base that this appeals to: experienced players who are willing to take a chance and can spend the $2,000-plus that boutique amplifiers cost.” Greg Bayles of Make’n Music with a Bogner amp stack A LABOR OF AMP LOVE n the other side of the fence, the economics are equally stark. Joe Naylor started his eponymously named brand of guitar amplifiers in 1994 using capital scoured from friends, family, credit cards, personal loans and the sale of a business whose site had been the manufacturing home for the 15 or so amplifiers he could build per month in Warren, Mich. (The boutique amp phenomenon is centered in the Midwest for reasons no one can explain, as opposed to the indie amp movement of the 1970s O Boutique amps can mean profit and prestige for dealers, but require an investment. Is it worth the risk? which was heavily concentrated in California.) By 1997, he had sold his interest in the business and even his name to another entrepreneur whose fortunes were as dismal as his had been. “You start out strong—there are people who like to jump on something new,” Naylor said. “The hard part is keeping the buzz going when you’re up against big brand names.” Joe Naylor now owns Reverend Musical Instruments, JULY 2005 | MUSIC INC. | 55 “It’s a pretty narrow niche of the customer base that this appeals to: experienced players who are willing to take a chance and can spend the $2,000-plus boutique amplifiers cost.” Dan Tracey, World Music “You have to get the amps in the hands of the sales force on the floor. You need them to explain to the customer why they should be interested in a $2,000 amplifier.” Brian Gerhard, Top Hat Amplification “[Carrying boutique amps] sets us apart from the big retailers. On the independent level, we have more latitude.” Greg Bayles, Make’n Music 56 | MUSIC INC. | JULY 2005 which started out in the boutique electric guitar market and branched out into amplifiers, turning out nearly 50 per month. He said the lessons learned from his first go-round are helping make this business successful. Most start-up amplifier companies fail, and of those that do persevere, the rewards are often minimal. Boutique amps are rarely sold on a consignment basis; the sale of one amp often directly funds the manufacture of the next one. “‘It’s a living’ is the best I can say,” said Brian Gerhard, who recently moved his Top Hat Amplification company from the high-overhead environs of Anaheim to the more cost-effective Raleigh, N.C., area. “Any significant money came from the real estate I had the business on.” The exception many point t o i s M e s a B o o g i e, w h o s e amplifiers became highly successful in the 1980s when many California rock artists began using them. The company’s dual-rectifier preamp design was also cited as being an element that helped the company stand out and gain acceptance among musicians and retailers. Boutique amps tend to be aimed at older vintage-sound aficionados rather than young “shredders.” Still, amp makers have developed a set of strategies to break out of the pack. “You have to get the amps in the hands of the sales force on the floor,” Gerhard said. “Often, the experienced store owners or managers will buy them to play themselves in clubs and on gigs. But the younger sales people tend to stick to the name brands. You need them to explain to the customer why they should be interested in a $2,000 amplifier.” Gerhard sends banners and other promotional materials to retailers to generate in-store buzz, adding that he rarely uses co-op advertising. Naylor said that making the rounds at trade and guitar shows, such as NAMM and the Dallas Guitar Show, is important. “NAMM’s expensive, but that’s where you get everyone in one place,” he said. “So it can be worth it.” Guy Headrick, co-owner of Guytron Amplifiers, has been building between 15 and 25 units a month, costing $2,900 each, in his Troy, Mich., factory since 1997. He’s found some fairly reliable indicators to determine if a retail dealer i s a g o o d p ro s p e c t . T h o s e boasting a significant level of pro audio sales is one. “I like to see a dealer whose customers know the difference between a Shure and Neumann microphone,” he said. “Also, I look at the guitar lines they already carry. Is it Fender or is it Squier? They’re good clues as to whether the customer base is open to our kinds of amplifiers.” RETAILERS TORN he start-up amplifier genius remains a sort of artist in solder-laden manufacturing, though retail often takes a less romantic view of them. Tracey, who once assembled guitar amp rigs for George Lynch and Ace Frehley, said he looks forward to trolling the shows for “cool new tones.” Still, when it comes to committing to a boutique amp, he said, “I sit down with a Peavey 30 and ask the guy, ‘Why is your boutique amp so much better?’ It’s about being able to move the product.” The margins on boutique amps can make it worth the effort. Dean Moody, store manager at Rudy’s Music Stop on Manhattan’s famed MI retail T strip along West 48th Street, pegs the profits on exotic handwired amps at between 25 and 40 percent. Moody monitors the grapevine for names of boutique marquees, using buzz as the barometer to determine if he’ll commit to buying and setting it up in the rear room, the store’s exclusive space for guitar amps. “If we love it, we’ll buy it,” he said. “If we don’t love it, but if we think some musicians will like it, we’ll offer the manufacturer some floor space, which is a sort-of consignment, I guess.” Greg Bayles, founder of Make’n Music, has made boutique products a major part of his inventory for nearly 30 ye a r s a n d c o n s i d e r s t h e i r inventors to be artists. He mentored Rheinhold Bogner when the Eastern European immigrant was a newly arrived teenager in Los Angeles, selling the first Bogner amp to Eddie Van Halen and buying all of Bogner’s production for more than a year, providing the company with a foundation that helped give it a strong hold in the boutique market. However, Bayles said, there are parallels with the larger music business. “I’ve had dealings with boutique guys who also sell direct to the customer on the side, using your store as a showroom,” he said. “Some o f t h e m d o n ’ t re a l i z e t h a t that’s wrong—they’re not as sophisticated about the business of selling as they are of electronics. But some of them d o k n ow. N o t eve r yo n e i s totally scrupulous.” WEB & ENDORSEMENT DYNAMICS he Internet has also become a double-edged sword, with positive “reviews” often posted by the amp’s own manufacturers. (A tactic much of American business has been accused of in T recent years.) “There’s a lot of ulterior motives in what you see on the Web,” Bayles said. “And the chat rooms devoted to guitar amps are populated with guys who type more than they play.” Endorsements are another issue. Bayles asserts that Matchless had a policy in its early days that impacted his Los Angeles store, which closed in 1995. “If you were in a big band, you got a free amp. That positioned them to compete with me for the very customers that you sell these kinds of products to.” But the pluses are there. Aside from good margins when a new amp starts to sell as a result of positive word of mouth, the boutique guitar amp gives the independent store a unique product often not found at large chain retailers. Boutique amps are rarely discounted, they’re not subject to simulations by amp modeling software, and rival stores often can’t use them as the basis for price wars. “It sets us apart from the big retailers,” Bayles said. “They’re like McDonald’s in that they need to know that a certain product is going to do a certain amount of volume before they can make the decision to commit to it. On the independent level, we have more latitude.” “The level of added value they can bring to a store is often significant,” Moody said. “At a time when we see a lot of conglomerations in this business, it’s accompanied by a lack of innovation,” Tracey said. “That’s what the boutique guys bring to the table.” MI The Empires Strike Back he boutique amp phenomenon has not escaped the notice of larger amp makers. Both Fender and Marshall now offer hand-assembled, limited-edition products. Fender’s ’57 Twin Reverb and ’65 Vibroverb reissues list at nearly $3,000. And in a move that underscores the current influence of boutique amp makers, Fender recently inked a deal with Victoria Amplifier, whose eight employees in a small Chicago suburb will soon begin hand-making and -wiring a line of Gretsch-branded boutique amps. “Fender had been trying to pull off a credible boutique amp of its own for years through its Custom Shop, but I truly think that they were getting tired of seeing their efforts— which were often quite good—trashed on the Internet bulletin boards by people who assume that a large company can’t make a boutique amp,” said Mark Baier, president of Victoria. According to Baier, the deal gives Fender the authenticity of a genuine boutique crafting the amplifiers. He said they’ll use carbon-composition resistors instead of the cheaper Asian ones he alleges Fender often uses as part of its mass manufacturing process. “It validates the Gretsch amps and the whole concept of boutique amps, which will help everyone at retail,” he said. “And it’s a perfect opportunity to grow my company on Fender’s dime.” —D.D. T JULY 2005 | MUSIC INC. | 57