transnational teaching at uow - Transnational Teaching Teams

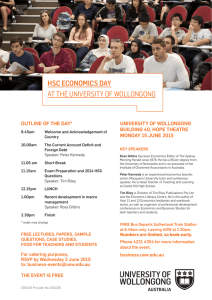

advertisement