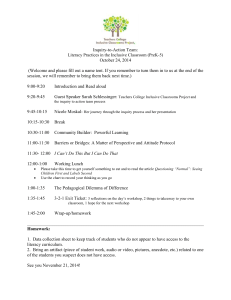

Information Literacy to Inquiry: A Timeline

advertisement