10 Pricing Strategies

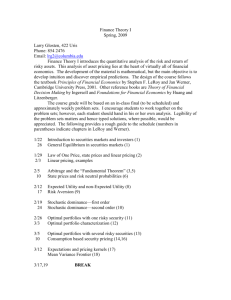

advertisement