Team 15 Final Brief - Copies - University of Cincinnati College of Law

2012 AUGUST A. RENDIGS, JR.

NATIONAL PRODUCTIONS LIABILITY MOOT COURT COMPETITION

No. 12-24-36480

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CRAWFORD

Spring Term 2012

Vortex Recreational Systems,

Petitioner

-v-

Jennifer Bates,

Respondent

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF CRAWFORD

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Team No. 15

Counsel for Petitioner

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................................................................................. iii

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ....................................................................................................v

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................................................................1

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS ..............................................................................................2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................................................................................8

ARGUMENT ...........................................................................................................................9

I. THE WELLS COUNTY COURT OF COMMON PLEAS ABUSED ITS

DISCRETION IN DENYING IN PART THE ADMISSIBILITY OF VORTEX’S

SUBMITTED EXPERT EVIDENCE UNDER CRAWFORD RULE OF

EVIDENCE 905 AND DAUBERT ’S PRESUMPTION OF ADMISSIBILITY. ..............10

A. Under Crawford Rule of Evidence 905 and Daubert , the Wells County Court of

Common Pleas abused its discretion in ruling Mr. Michael Robinson’s Materials

Testing Report inadmissible expert evidence because his engineering education qualifies him as an expert. .............................................................................................11

B. The Affidavit of Mr. Roger Sullivan was properly admitted by the Wells County

Court of Common Pleas as expert evidence because of his firsthand experience and knowledge in conducting water sports on the Crawford River. .............................13

II. THE CRAWFORD COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN REVERSING IN PART

THE WELLS COUNTY COURT OF COMMON PLEAS’ GRANT OF

SUMMARY JUDGMENT IN FAVOR OF VORTEX ON THE RESPONDENT’S

PRODUCT LIABILITY CLAIMS. ...................................................................................15

A. The Appellate Court properly affirmed the lower court’s grant of Vortex’s motion for summary judgment on Respondent’s manufacturing defect claim because the Splash Rower did not deviate from Vortex’s intended design. .................16

B. The Appellate Court erred in reversing the lower court’s grant of Vortex’s motion for summary judgment on Respondent’s design defect claim because the

Splash Rower was reasonably safe and Respondent did not present a reasonable alternative design. ..........................................................................................................17

C. The Appellate Court erred in reversing the lower court’s grant of Vortex’s motion for summary judgment on Respondent’s warning defect claim because

Vortex’s “For Recreational Use Only” warning alerts users to the existence and nature of the product's risks. ..........................................................................................23

CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................................29

APPENDIX FOR THE PETITIONER ...................................................................................30 ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

United States Supreme Court Cases

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett , 477 U.S. 317 (1986)……………………………….….. 9, 16, 22, 23, 28

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharm., Inc.

, 509 U.S. 579 (1993)………………… 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Gen. Elec. Co. v. Joiner , 522 U.S. 136 (1997)…………………………………………... 9, 13, 15

Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael , 526 U.S. 137 (1999)………………………………………….. 11

United States Federal Circuit Court Cases

Larabee v. M M & L Int’l Corp.

, 896 F.2d 1112, 1116 n. 6 (8th Cir. 1990)…………………… 11

Raskin v. Wyatt Co.

, 125 F.3d 55 (2nd Cir. 1997)……………………………………………… 19

United States Federal District Court Cases

Canino v. HRP, Inc.

, 105 F.Supp.2d 21 (D.N.Y. 2000)……………………. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Lappe v. Am. Honda Motor Co.

, 857 F.Supp. 222 (D.N.Y. 1994)……………….. 9, 11, 12, 13,14

Zwillinger v. Garfield Slope Hous. Corp.

, No. CV 94 4009(SMG), 1998 WL 623589, at *1

(D.N.Y. Aug. 17, 1998)………………………………………………………………………... 12

State Court Cases

Banks v. ICI Ams., Inc.

, 450 S.E.2d 671 (Ga. 1994)………………………………... 19, 20, 21, 22

Blue v. Envtl. Eng’g, Inc.

, 828 N.E.2d 1128 (Ill. 2005)……………………………….... 21, 27, 28

Branham v. Ford Motor Co.

, 701 S.E.2d 5 (S.C. 2010)………………………………... 19, 20, 21

Gray v. Badger Mining Corp.

, 676 N.W.2d 268 (Minn. 2004)…………………………….. 25, 26

Moore v. Ford Motor Co.

, 332 S.W.3d 749 (Mo. 2011)……………………………….. 24, 25, 28

Myrlak v. Port Auth. of New York & New Jersey , 723 A.2d 45 (N.J. 1999)………………. 16, 17

Parish v. Jumpking, Inc.

, 719N.W.2d 540 (Iowa 2006)……………………………………. 26, 28

Powers v. Taser Int’l, Inc.

, 174 P.3d 777 (Ariz. Ct. App. 2008)……………………………….. 24

Williams v. Bennett , 921 So.2d 1269 (Miss. 2006)……………………………………... 18, 19, 22 iii

Rules and Regulations

Craw. R. Evid 98………………………………………………………………………………... 10

Craw. R. Evid. 905…………………………………………………………………………… 9, 10

Craw. R.C. § 5255………………………………………………………………………………. 21

Craw. R.C. §895.52……………………………………………………………... 14, 22, 23, 24, 26

Court Orders

Bates v. Vortex Recreational Sys.

, No. 10-CV-9568

(Craw. Com. Pl. 2010). ……………………………………………..10, 11, 13, 14, 17, 23, 27, 28

Bates v. Vortex Recreational Sys.

, No. 45-CA-90180 (Craw. Ct. App. 2011)…………. 15, 23, 24

Secondary Sources

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 (1998)…………………………………. 10, 15, 16

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(a) (1998)………….…………………….. 9, 15, 16

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(b) (1998)……………………. 9, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(c) (1998)………………………..…. 10, 16, 23, 28

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. d (1998)………………….. 16, 17, 19, 21, 22

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. i (1998)…………………………... 16, 23, 24

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. j (1998)…………………………... 26, 27, 28

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. q (1998)………………………………….. 22

Purdue University College of Engineering, Back of POS , P

URDUE

U

NIVERSITY

,

https://engineering.purdue.edu/ChE/Academics/.../Back%20of%20POS.pdf

(last visited Mar. 7, 2012, 7:30 PM)……………………………………………...……………. 12

Safety Code of American Whitewater , A

MERICAN

W

HITEWATER

,

http://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/Wiki/safety:start?#vi

(last visited Mar. 7, 2012, 7:30 PM)………………………………………………….... 22, 24, 27 iv

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1.

Whether the Wells County Common Pleas Court abused its discretion when ruling on the admissibility of Vortex’s submitted expert evidence under Crawford Rule of Evidence

905 considering Daubert ’s presumption of admissibility?

2.

Whether the Crawford Court of Appeals for the Fifth District erred in granting in part and denying in part summary judgment in favor of Vortex on Respondent’s product liability claims? a.

Whether the appellate court properly granted summary judgment in favor of

Vortex on Respondent’s manufacturing defect claim? b.

Whether the appellate court erred in denying summary judgment in favor of

Vortex on Respondent’s design defect claim? i.

Whether the Respondent has met the required burden of proof that a reasonable alternative design exists and whether such reasonable alternative design, if any, should have been implemented by Vortex under c.

Whether the appellate court erred in denying summary judgment in favor of

Vortex on Respondent’s warnings defect claim? a risk-utility standard? i.

Whether Vortex’s warning language of “For Recreational Use Only” adequately warned the Respondent against foreseeable risks of harm and whether suck risks of harm were “open and obvious” to the Respondent?

3.

Whether the Petitioner’s product defects, if any, were the proximate cause of the

Respondent’s injury? v

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The respondent, Jennifer Bates, filed a claim for strict products liability against the petitioner, Vortex Recreational Systems (Vortex). The claim alleged that the respondent’s Splash

Rower was defectively manufactured and designed and that Vortex failed to provide adequate warnings as to the product’s proper use. Vortex sought to admit expert testimony in the form of

Mr. Michael Robinson’s Materials Testing Report and an Affidavit of Mr. Roger Sullivan. The

Wells County Court of Common Pleas admitted the Affidavit of Mr. Sullivan. In admitting this evidence and viewing the record in the light most favorable to the respondent, the Wells County

Court of Common Pleas entered Summary Judgment in favor of Vortex on all of the respondent’s claims.

The respondent then appealed the grant of summary judgment to the Crawford Court of

Appeals for the Fifth District Wells County. The Crawford Court of Appeals reversed the admittance of the Affidavit of Mr. Roger Sullivan. The court affirmed the trial court’s granting of Summary Judgment on the manufacturing defect claim, but reversed as to the other two counts.

This appeal to the Supreme Court followed.

1

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Miguel Jimenez and Sean Thompson created Vortex Recreational Systems (“Vortex”) in

March 2008 hoping to form “A Company That Serves Those That Have Served Us”. (R 2-3) 1 .

Mr. Jimenez and Mr. Thompson were both U.S. Marines who had completed two tours in Iraq between 2005 and 2008. (R 1). While in Iraq, Mr. Jimenez and Mr. Thompson’s unit attempted to secure a portion of highway outside of Northern Baghdad when a fellow Marine, Victor

‘Vortex’ Jackson, was struck by an Improvised Explosive Device (IED). (R 3). Mr. Jackson died immediately from injuries suffered in this blast. (R 3).

Mr. Jimenez and Mr. Thompson realized the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan led to a dramatic increase in military amputees who were returning home from service. (R 3). They witnessed these sacrifices first hand, and decided to start a business honoring their fallen comrade Mr. Jackson. Vortex Recreational Systems was born in his honor. (R 2).

After completing their Marine Corps. service in February 2008, Mr. Jimenez moved to

Mr. Thompson’s home State of Crawford to begin working on the business concept. (R 3). The business is incorporated in the State of Crawford, and operates a manufacturing and distribution facility in the City of Wells. (R 2). Vortex designs, fabricates, and sells recreational prosthetic attachments that provide amputees the ability to participate in activities that require the functionality of a natural limb. (R 2). Each attachment is designed to focus on a particular recreational activity. (R 2). These activities include baseball, basketball, golf, tennis, swimming, and rafting. (R 2). Vortex primarily focuses its marketing toward military amputees injured during combat. (R 2).

Mr. Thompson and Mr. Jimenez began designing recreational prosthetic attachments in the spring of 2009, and released Vortex’s baseball attachment in July 2009. (R 3).

1 “R” refers to Bates v. Vortex Recreational Sys.

, No. 10-CV-9568 (Craw. Com. Pl. 2010).

2

The attachment for canoeing and rafting, known as the “Splash Rower”, is the product at issue in this case. (R 3).

The Splash Rower is designed to attach to a standard prosthetic arm, while allowing the user to grasp an oar or paddle. (R 3). The Splash Rower includes two interlocking parts, Part A and Part B. (R 3). Part A forms the device’s lower half with one end attaching to an oar or paddle, similar to a clinched fist. (R 3). The oar attachment may be adjusted using a tightening screw located on the top. (R 3). Part A’s opposing cylindrical end screws onto one end of Part B, forming an adjustable elbow. (R 3). This joint may be adjusted to give varying angles, which allows for a varying range of motion. (R 3). The interlocking parts of A and B are held securely in place through a series of pegs located on Part A, and peg holes located on Part B. (R 3). To release the attachment, the pegs may be pressed inward and Part A may be pulled upward, out of

Part B. (R 3). The opposing end of Part B attaches to any standard prosthetic limb with a cylindrical screw end. (R 3).

Vortex builds the Splash Rower out of graphite, choosing this material because it would provide the flexibility needed to create a natural rowing motion. (R 3). Vortex considered building the Splash Rower from other materials, including iron, but due to the flexibility constraints and cost considerations, elected to use graphite. (R 3). Suppliers in Wells indicated that graphite is approximately twenty percent (20%) cheaper than iron. (R 3). Vortex’s initial concerns regarding the strength of graphite were quelled following materials testing at Crawford

Tech University (CTU). (R 3). Vortex contacted CTU in search of a student intern who could assist in the materials testing. (R 3). Vortex interviewed a number of candidates before selecting a senior engineering student, Mr. Michael Robinson. (R 3). Vortex reached an agreement with

CTU’s engineering department allowing Mr. Robinson to use CTU’s Research and Development

3

Center. (R 3). As part of the agreement, Mr. Robinson would be compensated $15/hr. as a co-op student, and Vortex agreed to purchase all necessary supplies and equipment. (R 3). Vortex agreed to donate any permanently installed equipment to CTU for future student research, and considered the partnership as an opportunity to give back and become engaged in the local community. (R 3-4).

Mr. Robinson conducted the materials testing under the supervision of Dr. Gregory Scott, who holds a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from Purdue University, and a Ph.D. in Chemical

Engineering from Ohio State University. (R 4). Dr. Scott completed his B.S. degree in May

2003, and his Ph.D. in June 2008. (R 4). Dr. Scott began teaching chemical engineering courses at CTU in September 2009. (R 4). Dr. Scott’s supervision over Mr. Robinson included meeting to discuss plans for the testing procedure, two meetings during testing to discuss Mr. Robinson’s progress, and again to discuss Mr. Robinson’s findings. (R 4). Additionally, Dr. Scott signed out an access card to Mr. Robinson when he needed access to the lab. (R 4).

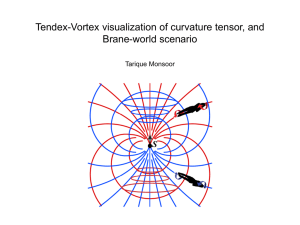

In October 2009, Mr. Robinson began materials testing on the Splash Rower for Vortex.

(R 4). Mr. Robinson conducted testing on an iron Splash Rower and a graphite Splash Rower. (R

4). Mr. Robinson used a motorized lap pool with a bolted-down wood stand. Each wood stand had a standard prosthetic arm attached. (R 4). Mr. Robinson used this testing apparatus to compare the strength of graphite to the strength of iron in various currents of water. (R 4). The motorized lap pool had three test settings, each varying the speed in miles per hour (mph) of the water current in the pool. (R 4). Mr. Robinson tested the Splash Rower at low speed (3 mph), medium speed (7 mph), and high speed (10 mph). (R 4). Sixty Splash Rowers were tested, thirty made from graphite and thirty made from iron. (R 4). Ten graphite Splash Rowers, and ten iron

Splash Rowers were tested at each speed. (R 4).

4

Mr. Robinson attached each Splash Rower to the wooden stand and to a standard paddle before submerging the paddle into the pool. (R 4). Each Splash Rower was tested for twenty minutes with ten minutes having a flow against the submerged paddle, and ten minutes having a flow from behind the paddle. (R 4). After each run, Mr. Robinson recorded the results for each test creating three categories: (1) remained attached with no physical damage, (2) remained attached with a cracked or bent shape; and (3) snapped apart. (R 4). All thirty iron Splash

Rowers tested fell within category 1, remaining attached with no physical damage. (R 4).

Twenty-Eight graphite Splash Rowers also feel within category 1, but Mr. Robinson noticed two graphite Splash Rowers bent slightly during the high-speed test. (R 4). Mr. Robinson also noted that all sixty Splash Rowers remained attached during the course of testing. (R 4).

The results of Mr. Robinson’s testing under Dr. Scott’s supervision, along with test conclusions, were reported to Vortex to assist in the material selection for the Splash Rower. (R

4). Vortex determined, based on the Materials Testing Report, that graphite was a safe and reliable material for us in the Splash Rower. (R 4). The results indicated negligible differences between iron and graphite under recreational conditions. (R 4). The Splash Rower went on sale in December 2009, priced at seven hundred and fifty ($750), and over one thousand were sold during 2010. (R 4).

Respondent, Ms. Jennifer Bates, is a twenty-four year old woman living in Old Haven, approximately twenty miles south of Wells. (R 4). She became an amputee during a vehicular accident in February 2004, losing her left forearm. (R 4-5). She was subsequently fitted with a standard prosthetic arm in June 2004, and completed six month of rehabilitation aimed toward adjusting to daily functions using the prosthetic arm. (R 5).

5

The Respondent learned about Vortex from a customer while working as a cashier in a retail store. (R 5). The customer was a military amputee recovering from injuries sustained while in Iraq, and mentioned a brochure he received from Vortex. (R 5). The brochure outlined

Vortex’s recreational attachments available for military amputees. (R 5). The Respondent became interested after this conversation, and subsequently requested a catalog from Vortex. (R

5).

After receiving a catalog at her residence, she purchased a Vortex Splash Rower in June

2010. (R 5). The Splash Rower arrived in a camouflage package, and upon opening the package, the respondent found a slip of paper with the words “FOR RECREATIONAL USE ONLY” written in bold, red letters. (R 5). The Respondent also noticed that the package contained a brochure featuring information regarding other Vortex products. (R 5).

The Respondent selected the Splash Rower attachment because of her interest in water sports, having kayaked twice with a few friends the summer before her accident. (R 5). She had not kayaked since her accident, but decided she wanted to try kayaking again using the Splash

Rower. (R 5). In addition to the Splash Rower, she also purchased a new kayak, double sided paddle, and a life jacket. (R 5).

The Respondent set out on June 22, 2010 with a friend to use her Splash Rower for the first time. (R 5). The Respondent planned a twenty-mile route along the Crawford River, finishing southwest of Wells where her friend would pick her up. (R 5). The Crawford River extends the length of the state, flowing north to south along the western edge of Wells. (R 5).

The weekend prior to June 22 included thunderstorms and heavy rain, thus making June the rainiest month in the past year. (R 5). The weather was sunny and clear the morning the respondent began her kayaking. (R 5). The Respondent, with her friend’s assistance, climbed

6

into her kayak, attached her Splash Rower and paddle, and pushed off the bank. (R 5). She had not kayaked since her accident and only kayaked twice her life, but set out on her route alone. (R

5). She had no prior knowledge of the Crawford River, and did not scout the river prior starting her route. (R 5).

Approximately five miles into her planned route the respondent encountered a narrow passage. She struggled steering and maneuvering her kayak around the exposed rocks and floating branches. (R 5). As the kayak continued to pick up speed, she dunked her paddle deep into the water, alternating sides in an attempt to slow the kayak down. (R 5). The Vortex Splash

Rower snapped while submerged deep into the water, causing her to lose her paddle. (R 5). The kayak spun, flipped over, and ejected the Respondent from the kayak. (R 5). The strong currents from the swollen Crawford River pulled the Respondent under the water where she hit a cluster of rocks. (R 5). The life jacket then pulled her to the surface. (R 5). A mile downstream, a fisherman pulled her from the water and took her to the hospital. (R 6). The collision with the rocks caused a spinal injury paralyzing her from the waist down. (R 6). Vortex manufactures and designs the Splash Rower for recreational purposes, as indicated by the warning the Respondent saw in the Splash Rower packaging. (R 2, 5).

7

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The petitioner, Vortex Recreational Systems, is entitled to summary judgment on

Respondent’s product liability claims because no genuine issue of material fact exists, even when the evidence is viewed in a light most favorable to the nonmoving party. Vortex presents two expert witnesses qualified in their knowledge, skill, experience, training, and education, which builds a reliable foundation, and shows their testimony is relevant, thus the courts below erred in failing to admit all of Vortex’s submitted expert evidence.

Respondent has failed to establish a genuine issue of material fact on her product liability claims because she did not show that her Splash Rower deviated from its intended design, that a reasonable alternative design existed for the Splash Rower, or that the warning, “FOR

RECREATIONAL USE ONLY”, was inadequate to alert her to foreseeable harms. Vortex’s expert witnesses show the Splash Rower design was reasonably safe for its intended use, and the accompanying warnings were sufficient to draw attention to foreseeable harms. The court must review the admissibility of Vortex’s submitted expert witnesses under an abuse of discretion standard, giving deference to the Wells County Court of Common Pleas’ discretion regarding the admissibility of expert testimony. The court must review the grant of summary judgment de novo .

8

ARGUMENT

The petitioner, Vortex Recreational Systems (Vortex), is entitled to summary judgment on Respondent’s product liability claims because no genuine issue of material fact exists regarding her manufacturing, design, and warning defect claims. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett , 477

U.S. 317, 322-23 (1986). In support of its motion, Vortex presents two expert witnesses qualified in their knowledge, skill, experience, training, and education, thus providing a reliable foundation. Lappe v. Am. Honda Motor Co.

, 857 F.Supp. 222, 226 (D.N.Y. 1994). Because

Vortex can show that their testimony is relevant to determining this case, the courts below erred in failing to admit all of Vortex’s submitted expert evidence. Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharm.,

Inc.

, 509 U.S. 579, 592 (1993); Craw. R. Evid. 905. The court must review the admissibility of

Vortex’s submitted expert witnesses under an abuse of discretion standard, giving deference to the Wells County Court of Common Pleas’ discretion regarding the admissibility of expert testimony. Gen. Elec. Co. v. Joiner , 522 U.S. 136, 146 (1997); Craw.R.Evid. 905.

The Respondent has failed to show that a genuine issue of material fact exists as to each of her product liability claims, even when the evidence is construed in the light most favorable to her. Celotex Corp.

, 477 U.S. at 322-23. The Respondent has failed to establish a genuine issue of material fact on her manufacturing defect claim because she did not show that her Splash Rower deviated from its intended design. Celotex Corp.

, 477 U.S. at 322-23; Restatement (Third) of

Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(a) (1998). There exists no genuine issue of material fact on her design defect claim because she failed to establish the existence, explicitly or implicitly, that a reasonable alternative design existed for the Splash Rower. Celotex Corp.

, 477 U.S. at 322-23;

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(b) (1998). Vortex’s warning, “FOR

RECREATIONAL USE ONLY”, was adequate to alert the Respondent to the foreseeable harms.

9

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(c) (1998). The actions taken by the Respondent in kayaking a Class III rapid with minimal experience also serves as an intervening cause. Bates v.

Vortex Recreational Sys.

, No. 10-CV-9568 (Craw. Com. Pl. 2010). Vortex’s expert witnesses show the Splash Rower design was reasonably safe for its intended use, and the accompanying warnings were sufficient to draw attention to foreseeable harms. Restatement (Third) of Torts:

Prods. Liab. § 2 (1998). The court must review the grant of summary judgment de novo .

Craw.R.Evid. 98.

I. THE WELLS COUNTY COURT OF COMMON PLEAS ABUSED ITS DISCRETION

IN DENYING IN PART THE ADMISSIBILITY OF VORTEX’S SUBMITTED EXPERT

EVIDENCE UNDER CRAWFORD RULE OF EVIDENCE 905 AND DAUBERT ’S

PRESUMPTION OF ADMISSIBILITY.

Expert witness evidence assists the trier of fact in a cause of action where scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help determine a fact in issue. Craw. R. Evid. 905.

An expert may offer evidentiary testimony based on sufficient facts or data, or testimony that is the product of reliable principles and methods that the witness has applied reliably to the facts in the present case. Id.

The Supreme Court in Daubert held a presumption exists for the admissibility of evidence so long as the principles outlined in the applicable rules of evidence are satisfied. Daubert , 509 U.S. at 597. Several Federal Courts have construed expert qualifications liberally, holding that “the expert should not be required to satisfy an overly narrow test of his own qualifications”. Canino v. HRP, Inc.

, 105 F.Supp.2d 21, 27 (D.N.Y. 2000). Vortex’s proffered expert witnesses meet these liberal qualifications through their knowledge, experience and education, thus satisfying the presumption of admissibility. Daubert , 509 U.S. at 594;

Canino , 105 F.Supp.2d at 27. Expert testimony must also have a tendency to make the existence of any fact of consequence more or less probable than it would be without the evidence. Daubert ,

509 U.S. at 592. Each expert presented offered reliable expert testimony that is relevant to

10

making consequential facts more or less probable than it would be without the submitted evidence. Daubert , 509 U.S. at 592; Canino , 105 F.Supp.2d at 27. This court should admit both experts’ testimony because Vortex showed that the proffered expert evidence is reliable and relevant, and the court should err on the side of admissibility. Daubert , 509 U.S. at 594; Lappe ,

857 F.Supp. at 226 (citing Larabee v. M M & L Int’l Corp.

, 896 F.2d 1112, 1116 n. 6 (8th Cir.

1990)).

A. Under Crawford Rule of Evidence 905 and Daubert , the Wells County Court of

Common Pleas abused its discretion in ruling Mr. Michael Robinson’s Materials Testing

Report inadmissible expert evidence because his engineering education qualifies him as an expert.

Mr. Michael Robinson qualifies as an expert witness because of his knowledge and education earned through his study of engineering at Crawford Tech University (CTU). See

Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael , 526 U.S. 137,148 (1999); Daubert , 509 U.S. at 592. Mr.

Robinson’s material testing, under the supervision of Dr. Gregory Scott, reliably applied his expert engineering principles and reliably applied them to the facts in this case. See Kumho,

526 U.S. at 148; Daubert , 509 U.S. at 592. Several courts have held that a lack of a degree in a narrowly defined field does not prohibit a witness from testifying as an expert, and that lack of specialization affects the weight of his opinion, not its admissibility. Canino , 105

F.Supp.2d at 28; Lappe , 857 F.Supp. at 226.

The Wells Court of Common Pleas abused its discretion when considering the qualifications of Mr. Robinson because it viewed his qualifications narrowly. See Canino , 105

F.Supp.2d at 27; Bates , No. 10-CV-9568. The court focused its discussion on Mr. Robinson’s lack of a degree, rather than looking at a broader interpretation of his qualifications. See

Canino , 105 F.Supp.2d at 27.

Mr. Robinson has clearly met the minimum qualifications set forward by courts through his engineering studies at CTU, along with Dr. Scott’s oversight.

11

See Zwillinger v. Garfield Slope Hous. Corp.

, No. CV 94 4009(SMG), 1998 WL 623589, at

*7 (D.N.Y. Aug. 17, 1998). The supervision of Dr. Scott further reinforces Mr. Robinson’s qualifications as an expert because Daubert specifically viewed peer review as a factor in determining qualification. See 509 U.S. at 593. Dr. Scott’s background in Chemical

Engineering does not alter his qualifications because an expert may stay within a reasonable confine of his or her subject area, which is engineering in this matter. See Lappe , 857 F.Supp. at 226-27. Dr. Scott reviewed Mr. Robinson’s work at multiple project stages to discuss the desired testing procedures, overall testing progress, and ultimate findings. By listing Dr.

Scott’s name on the cover page, Mr. Robinson’s report indicates Dr. Scott’s oversight of the testing procedures and application of reliable engineering principles. This peer review from

Dr. Scott ensured Mr. Robinson followed all engineering principles, and negates Mr.

Robinson’s lack of a diploma. Daubert , 509 U.S. at 593. Mr. Robinson performed all the work, and Dr. Scott’s supervision and peer review qualify Mr. Robinson as an expert. See id.

Dr. Scott’s qualifications were also viewed in a narrow scope by the trial court. See

Canino , 105 F.Supp.2d at 28-29. This is counter to other court opinions which establish that expert qualifications may be broad within their field. See id.

Dr. Scott holds a bachelor’s degree in Chemical Engineering from Purdue University, where the undergraduate engineering curriculum requires students to take six hours of engineering electives from a course list. Purdue University College of Engineering, Back of POS , P URDUE U NIVERSITY , https://engineering.purdue.edu/ChE/ Academics... /Back%20of%20POS.pdf (last visited Mar.

7, 2012, 7:30 PM). This course list includes twelve individual courses in Material Science

Engineering. Id.

Courts are directed to evaluate qualifications liberally and flexibly, rather than with an overly narrow test of the expert’s own qualifications. Canino , 105 F.Supp.2d at

12

27. Under this flexible view, Dr. Scott’s Chemical Engineering degree lends his credibility to

Mr. Robinson’s Materials Testing Report. See Daubert , 509 U.S. at 593.

The court does not question the reliability or relevance of Mr. Robinson’s report, noting that it was a well-done study. Bates , No. 10-CV-9568. This court should resolve doubts over an expert’s usefulness in favor of admissibility, allowing the jury to determine the weight of the opinion. Lappe , 857 F.Supp. at 226. The court’s role as a gatekeeper of evidence offers broad discretion in evidentiary admissibility, but the Wells County Court of Common

Pleas abused this discretion by creating an overly narrow set of qualifications for Mr.

Robinson. See Gen. Elec. Co. v. Joiner , 522 U.S. at 146; Daubert , 509 U.S. at 597. Mr.

Robinson’s report determined there were insignificant differences between the performance of an iron Splash Rower and a graphite Splash Rower. This report was based on reliable engineering principles, subject to testing and peer review. See Daubert , 509 U.S. at 593-

94. Further, the tests were run a total of thirty times per material to produce accurate results.

Like the trial court, this court should not find fault with Mr. Robinson’s principles.

Mr. Robinson’s engineering knowledge and Dr. Scott’s peer review qualify Mr.

Robinson’s report as expert testimony under Daubert ’s presumption of admissibility. See id.

This report is based on reliable engineering principles and is relevant in determining that the graphite Splash Rower was reasonably safe and is therefore admissible as expert evidence.

Daubert , 509 U.S. at 594; Canino , 105 F.Supp.2d at 27.

B. The Affidavit of Mr. Roger Sullivan was properly admitted by the Wells

County Court of Common Pleas as expert evidence because of his firsthand experience and knowledge in conducting water sports on the Crawford River.

The Wells County Court of Common Pleas properly admitted Mr. Roger Sullivan’s expert evidence because the court used its wide discretion in assessing the relevance of his

13

expert knowledge. See Daubert , 509 U.S. at 594; Lappe , 857 F.Supp. at 226. The court considered broader criteria than it would when assessing more scientific based knowledge.

See Bates , No. 10-CV-9568. Mr. Sullivan possesses thirty-years experience in water sports, including intimate knowledge of the Crawford River. His affidavit sheds light on the

Crawford River’s conditions in the days prior to the Respondent’s injury. Mr. Sullivan’s experience as a rafting guide, which qualifies as a water sport according to Craw. R.C.

§895.52, is relevant and meets the Daubert “gate keeping” standard because of his personal knowledge of the conditions the Respondent encountered while kayaking. See 509 U.S. at

597.

Though Mr. Sullivan may not specifically be a kayaker, his testimony is still relevant.

See Canino , 105 F.Supp.2d 21 at 28. For instance, in Canino , where an infectious disease doctor with no prior Hepatitis B experience qualified as an expert in the transmission of

Hepatitis B, the court held that because of his overarching qualifications as an infectious disease doctor, he qualified as an expert. Id.

at 26, 28. Similarly, Mr. Sullivan qualifies as an expert with regards to conducting water sports on the Crawford River because he has thirtyyears of rafting, a water sport, experience. See id.

at 28. The Canino court held the doctor’s qualifications in infectious disease allowed him to offer an expert opinion on Hepatitis B transmission, despite having no prior experience with the disease. Id.

Likewise, Mr. Sullivan has no known prior experience with kayaking, but his thirty-years experience rafting, and fifteen years experience guiding tours on the Crawford River, qualify him as an expert. See id.

This experience has given Mr. Sullivan expert knowledge of the river, its conditions during and after rain, as well was the experience level necessary to safely conduct water sports on the river.

14

The Appeals Court erred by failing to afford the lower court appropriate discretion in determining the admissibility of Mr. Sullivan’s affidavit. See Gen. Elec. Co. v. Joiner , 522

U.S. at 146; Bates v. Vortex Recreational Sys.

, No. 45-CA-90180 (Craw. Ct. App. 2011). The lower court properly qualified Mr. Sullivan, and determined his water sports experience was relevant. The distinction between rafting and kayaking, and its effect on the expert testimony, should be left to a jury. This distinction should merely affect the weight of the opinion, not its admissibility. Canino , 105 F.Supp.2d 21 at 28. The appeals court erred in determining that the witness failed to meet an overly and unnecessarily narrow set of qualifications in finding that his rafting experience did not provide him with the necessary and relevant knowledge of conducting water sports on the Crawford River. See id.

at 27. Because Mr. Sullivan’s years of experience with water sports in general qualify him as an expert, this court should admit his testimony. See id.

II. THE CRAWFORD COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN REVERSING IN PART

THE WELLS COUNTY COURT OF COMMON PLEAS’ GRANT OF SUMMARY

JUDGMENT IN FAVOR OF VORTEX ON THE RESPONDENT’S PRODUCT

LIABILITY CLAIMS.

Products liability claims stem from a product defective at the time of sale or distribution. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 (1998). Plaintiffs may claim a defective product due to a manufacturing defect, a defective design, or inadequate warnings.

Id. A manufacturing defect exists when a product deviates from its intended design, causing the product to not be reasonably safe. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(a)

(1998). A manufacturing defect must occur prior to arriving in the plaintiff’s hands, whether it occurred during manufacture, packaging, shipping, or distribution. Id.

Products contain a defective design when the foreseeable risks of harm could have been reduced by the selection of an alternative design, and failing to select the alternative design renders the product not

15

reasonably safe. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(b) (1998). A claimant carries the burden of proof to show that a reasonable alternative design was available at the time of sale or distribution. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. d (1998). A product may also be defective because of failure to properly instruct or warn about foreseeable risks posed by the product and those risks could have been avoided by proper instruction or warning. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(c) (1998). The omission of these warnings must then render the product not reasonably safe. Id.

Warnings alert users to the nature of product risks allowing them to take appropriate action to prevent harm or choose not to use the product, while instructions alert users how to use a product safely. Restatement

(Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. i (1998). A product defect exists when the product is not reasonably safe by manufacture, design, or warning and the burden of proving a product liability claim falls squarely on the claimant. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2

(1998).

A. The Appellate Court properly affirmed the lower court’s grant of Vortex’s motion for summary judgment on Respondent’s manufacturing defect claim because the

Splash Rower did not deviate from Vortex’s intended design.

The Splash Rower did not deviate from Vortex’s intended design and therefore no genuine issue of material exists regarding the Respondent’s manufacturing defect claim.

Celotex Corp.

, 477 U.S. at 322-23; Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(a) (1998).

The Respondent failed to establish that her injury was caused by a manufacturing defect. To prove the existence of a manufacturing defect, a plaintiff may rely on direct evidence or circumstantial evidence, but the Respondent has presented neither in this matter. Myrlak v.

Port Auth. of New York & New Jersey , 723 A.2d 45, 52 (N.J. 1999). A plaintiff may also eliminate other causes of failure, thus proving a defect; however, the Respondent has failed to

16

eliminate potential causes of failure for the Splash Rower. See id.

More specifically, she exceeded the product’s intended use by kayaking in a Class III rapid marked difficult without appropriate experience. See id.

at 53. The Respondent’s misuse of the Splash Rower potentially caused its failure, thus creating the basis for the lower court’s determination that no inference that the product’s failure was attributable to Vortex. Bates , No. 10-CV-9568.

The mere fact that the Respondent suffered an injury is not sufficient evidence to establish that the Respondent’s Splash Rower was defective. See Myrlak , 723 A.2d at 55. The court in Myrlak , where an overweight employee suffered injuries when his chair collapsed, held that the occurrence of an injury fails to establish the presence of a defect. 723 A.2d at 49,

55. The court also noted that the plaintiff failed to produce sufficient evidence, direct or circumstantial, that the chair was defective. Id.

at 55. As in Myrlak , where the court declined to extend res ipsa loquitor to products liability, this court should not allow the Respondent to rely on the mere fact that an injury occurred to prove a manufacturing defect existed. Because the Respondent failed to provide any evidence that her Splash Rower contained a manufacturing defect, this court should affirm the grant of summary judgment. See id.

B. The Appellate Court erred in reversing the lower court’s grant of Vortex’s motion for summary judgment on Respondent’s design defect claim because the Splash

Rower was reasonably safe and Respondent did not present a reasonable alternative design.

In order to successfully prove a claim for design defect, the Restatement (Third) of

Torts: Products Liability § 2(b) requires showing the existence of a reasonable alternative design. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. d (1998). A product is unreasonably safe when the foreseeable risks of harm may be reduced, at a reasonable cost, by a reasonable alternative design and the omission of that design renders the product not reasonably safe. Id.

Vortex urges the court to adopt a burden of proof requiring the

17

Respondent to explicitly prove the feasibility of a reasonable alternative design. See Williams v. Bennett , 921 So.2d 1269, 1275 (Miss. 2006).

The Respondent has not presented any evidence establishing the product could have been made safer through adoption of a reasonable alternative design. See id.

In Williams , where the plaintiff accidentally shot himself with a handgun, the court held the plaintiff failed to meet his burden of proof because he failed to produce explicit evidence of a reasonable alternative design that could have prevented his injuries. Id.

at 1270-78. The court applied three factors in finding that the plaintiff failed to prove his claim. Id.

at 1276-77. The court held that the plaintiff has to prove that the seller should have been aware of the product’s potential dangers, that the product “failed to function as expected”, and that a reasonable alternative design existed that could have negated any potential dangers. Id.

Because a trier of fact relies on explicit evidence to determine liability, the court held that the plaintiff failed to meet his burden on these three factors. Id.

at 1277.

The Respondent here has failed to explicitly establish the existence of a reasonable alternative design that could have prevented her injuries. See id.

at 1278. The Williams factors provide a road map for determining the evidentiary basis of a design defect claim. Id.

at 1276-

77. Mr. Robinson’s testing showed negligible differences between the iron and graphite

Splash Rower designs under recreational conditions because all sixty Splash Rowers remained attached throughout testing. Two graphite Splash Rowers bent during high speed testing due to graphite’s inherent flexibility. Graphite was chosen due to this flexibility after demonstrating sufficient strength, and this factor alone does not render the product unreasonably safe. Vortex, though knowledgeable of graphite’s flexibility, did not know, nor should it have known, that the graphite Splash Rower would snap when subjected to extreme

18

conditions. The Respondent’s Splash Rower functioned as designed, and only failed when subjected to conditions beyond its recreational purpose. See id.

While Vortex, through Mr.

Robinson, tested an iron Splash Rower, the Respondent failed to present explicit evidence that the iron Splash Rower was suitable for the Crawford River’s conditions and was a reasonable alternative design capable of preventing her injuries. See id.

The application of the factors used in Williams show that because Vortex did not know of any unsafe conditions, the Splash

Rower functioned as intended, and no feasible design alternative existed. Thus, under an explicit proof requirement, this court should grant Vortex’s motion for summary judgment.

See id.

If this court determines Mr. Robinson’s testimony does not qualify as expert testimony, then the court should not consider this evidence when determining the summary judgment motion. Raskin v. Wyatt Co.

, 125 F.3d 55, 66-67 (2nd Cir. 1997). Without the inclusion of Mr. Robinson’s report, the Respondent presents zero evidence to establish even the mere existence of a reasonable alternative design, much less evidence to establish an alternative design capable of preventing her harms. See Williams , 921 So.2d 1269 at 1276-77.

Alternatively, other courts have adopted an implicit test for establishing a reasonable alternative design that incorporates a risk-utility balancing test. Branham v. Ford Motor Co.

,

701 S.E.2d 5, 14 (S.C. 2010); Banks v. ICI Ams., Inc.

, 450 S.E.2d 671, 673 (Ga. 1994). A risk-utility balancing test may be applied to determine the feasibility of an alternative design.

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. d (1998). The burden of proof for establishing the reasonable alternative design rests solely with the Respondent. Id.

A design defect must render the product not reasonably safe from foreseeable risks posed by the product and the alternative design would have prevented these harms. Restatement (Third) of

19

Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(b) (1998). If this court chooses not to adopt the explicit proof requirement, Vortex requests the court adopt the risk-utility balancing test requiring implicit proof of a reasonable alternative design. See Branham , 701 S.E.2d at 14; Banks , 450 S.E.2d at

673.

Multiple jurisdictions interpreting the Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability have applied a risk-utility test finding that “the risks inherent in a product design are weighed against the utility or benefit derived from the product.” Banks , 450 S.E.2d at 673; see also

Branham , 701 S.E.2d at 14. For example, in Banks , where a child died from ingesting rodenticide, his estate alleged a claim for defective design of the product. Banks , 450 S.E.2d at 672. The risk-utility balancing test takes into account whether the manufacturer acted reasonably. Id .

at 673. The manufacturer has to look at any risk posed by the design, how useful the product is with its design, and how burdensome it would have been to eradicate any risks. Id.

at 673. The court also noted that any other design would have to be affordable. Id.

at

674. The court held that in deciding design defect claims, evidence could be provided that showed that a different design was safer, available, affordable, and technologically possible.

Id.

at 674-75.

The respondent has failed to provide any evidence of an alternative design. Vortex tested Splash Rowers made from two different materials, iron and graphite. In its testing,

Vortex found no discernible differences between the two materials. If the court declines to adopt an explicit proof requirement, then like the Banks court, this court should apply the riskutility test. Id.

at 673. Because of the Respondent’s failure to provide any evidence or proof of an alternative design whatsoever, Vortex is entitled to summary judgment even if this court

20

chooses to adopt a risk-utility test. See Banks , 450 S.E.2d at 673; Restatement (Third) of

Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. d (1998).

Because there is no clear set of factors used in determining when a manufacturer should be liable, the court can has wide discretion to consider a variety of factors. See Blue v.

Envtl. Eng’g, Inc.

, 828 N.E.2d 1128, 1140 (Ill. 2005); Banks , 450 S.E.2d at 675; Restatement

(Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. d (1998). The Respondent has not presented any factors that tip the risk-utility balancing test in favor of an alternative design. Vortex designed the Splash Rower with recreational activities in mind and considered weight, cost, flexibility, and strength. Graphite proved to be superior in weight, cost, and flexibility, and showed a negligible difference in strength. Because the Splash Rower was designed for recreational purposes only, the negligible difference between the strength of iron and graphite did not outweigh the benefits of graphite being lighter weight, less expensive, and more flexible.

After applying the risk-utility test, Vortex is entitled to summary judgment because the

Respondent failed to present a reasonable alternative design. See Blue , 828 N.E.2d at 1140;

Banks , 450 S.E.2d at 675; Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. d (1998).

This court should not adopt the consumer-expectations test because Restatement

(Third) of Torts: Product Liability § 2(b) specifically requires evidence of an alternative design. See Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(b) (1998). The Consumer

Expectations Test is born out of Restatement (Second), and is not applicable in a jurisdiction that has adopted the Restatement (Third). Branham , 701 S.E.2d at 14; Crawford R.C. § 5255.

The consumer expectations test focuses on the consumer, not the product itself, thus making it insufficient to determine a product’s design defect. Branham , 701 S.E.2d at 15. Providing

21

proof, either explicitly or implicitly, of a reasonable alternative design is a better means for determining a design defect. Id.

Regardless of which test this court chooses to apply, the Respondent fails to establish the causation element of her design defect claim. In each test, the Respondent must establish the design defect was the proximate or “but for” cause of her harm. Craw. R.C. 895.52;

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. q (1998). The Respondent’s use of the

Splash Rower beyond its intended recreational use serves as an intervening cause, breaking the causal chain between the product’s design and her harm. Restatement (Third) of Torts:

Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. q (1998). The Respondent chose to use the Splash Rower on the

Crawford River, a Class III river, after a weekend of thunderstorms and heavy rain without any training, experience, or knowledge of the conditions. A Class III rapid should be scouted prior to conducting water sports and includes high, irregular rocks with narrow passages requiring expert maneuvering. Safety Code of American Whitewater , A

MERICAN

W HITEWATER , http://www.americanwhitewater.org/ content/Wiki/safety:start?#vi (last visited

Mar. 7, 2012, 7:30 PM). The Respondent did not scout the Crawford River as advised by the

International Scale of River Difficulty , and had insufficient experience to navigate the rocks and narrow passages. Id.

Mr. Roger Sullivan’s affidavit proffers that the Respondent’s injuries would have occurred without a design defect.

Vortex is entitled to summary judgment because the Respondent has failed to provide proof, either explicitly or implicitly, of an alternative design. Celotex Corp.

, 477 U.S. at 322-

23; Williams , 921 So.2d 1269 at 1276-77; Banks , 450 S.E.2d at 675; Restatement (Third) of

Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. d (1998). No genuine issue of material fact exists regarding whether the Splash Rower contains a design defect and whether a reasonable alternative

22

design exists that would have prevented the Respondent’s injuries. Celotex Corp.

, 477 U.S. at

322-23. Additionally, the Respondent broke the causal chain by exceeding the Splash Rower’s recreational purpose. Therefore, this court should grant Vortex’s motion for summary judgment on the Respondent’s design defect claim.

C. The Appellate Court erred in reversing the lower court’s grant of Vortex’s motion for summary judgment on Respondent’s warning defect claim because Vortex’s

“For Recreational Use Only” warning alerts users to the existence and nature of the product’s risks

The Vortex Splash Rower is not defective because it included a sufficient warning by indicating “FOR RECREATIONAL USE ONLY” in the packaging, which alerted users to the existence and nature of the product’s foreseeable risks. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods.

Liab. § 2(c) (1998). Additionally, this warning instructed users on how to use the Splash

Rower safely. This warning indicated to the user that the product was to be used for relaxation and pleasure, not professional purposes. Craw. R.C. § 895.52. A product may be deemed defective if its warning fails to allow users to alter their behavior when using a product by alerting users to the existence and nature of a product’s foreseeable risks. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. i (1998).

The Crawford Court of Appeals took an overly broad construction of the word recreational, in conflict with Crawford’s own legislature’s definition of the word. Bates, No.

45-CA-90180. The Crawford legislature plainly states that the activity must be “undertaken for the purpose of exercise, relaxation or pleasure”. Craw. R.C. § 895.52. The trial court appropriately applied a distinction between recreational and professional activities, whereas the appellate court deemed all water sports and all levels of kayaking as recreational activity.

Bates , No. 10-CV-9568; Bates , No. 45-CA-90180. The Crawford legislature provides examples such as bicycling, but as the trial court properly noted, there is an obvious

23

distinction between riding a bicycle around town and competing in the Tour De France. Craw.

R.C. § 895.52. Similarly, there is a distinction between kayaking down a river with few obstructions where self-rescue is simple and kayaking down a Class III river notorious for having large rock formations with heavy currents and narrow passages. See Safety Code of

American Whitewater , A

MERICAN

W

HITEWATER

, http://www.americanwhitewater.org/ content/Wiki/safety:start?#vi (last visited Mar. 7, 2012, 7:30 PM). The warning “FOR

RECREATIONAL USE ONLY” is adequate because the Respondent’s activities fall outside the scope of Crawford’s recreational activity definition. Craw. R.C. § 895.52. The appeals court was correct in noting that the Crawford legislature defines water sports as a single activity, which would include kayaking, rafting, and canoeing. Bates , No. 45-CA-90180.

While the Respondent’s injuries were a foreseeable harm caused by a foreseeable risk,

Vortex negated these risks by including its “FOR RECREATIONAL USE ONLY” warning within the Splash Rower packaging. See Moore v. Ford Motor Co.

, 332 S.W.3d 749, 757

(Mo. 2011); Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. i (1998). Vortex owes a duty to warn users of the foreseeable harms that could be caused by the Splash Rower, but does not

“become the insurer of the safety of the product’s use.” Powers v. Taser Int’l, Inc.

, 174 P.3d

777, 784 (Ariz. Ct. App. 2008) (finding that strict liability is not an absolute liability in a case involving a taser with adequate warnings). The Respondent used the Splash Rower in a Class

III river, beyond recreational purposes, failing to heed Vortex’s warning. In consideration of

Vortex’s warning, the product was not used in a reasonably foreseeable manner when adhering to the warning. See Moore , 332 S.W.3d at 756 (finding that there are five causes of action in a failure to warn claim).

24

A manufacturer is liable for warning of foreseeable risks associated with using the product for its intended purpose. See id . For example, in Moore , where an obese woman was injured when her car seat collapsed after her vehicle was struck from behind, the court found that her use of the car, and its seat, was foreseeable to the manufacturer. Id.

at 754. The manufacturer did not provide a warning indicating the front seat may fail, due to excessive weight, during a collision. Id.

at 757. The front seat collapsing could cause an occupant to hit his or her head on the rear seat. Id.

This is the exact harm suffered by the plaintiff and the defendant’s failure to warn proximately caused the plaintiff’s injuries. Id.

at 763. The plaintiff, due to her obesity, looked for, and heeded, warnings regarding weight capacities when purchasing vehicles. Id.

at 755.

Vortex is not liable for the Respondent’s injury because she did not heed the warning when she exceeded the Splash Rower’s intended purpose. Unlike the defendant in Moore ,

Vortex included a warning written with red ink in bold, capital letters to negate any foreseeable harms. Id.

at 763. The court in Moore also found that, absent a warning, the plaintiff was using her vehicle in a manner intended by the defendant. Id.

at 757. Whereas here, the Respondent failed to heed Vortex’s warning by kayaking on a Class III rapid without training, thus using the product in a manner inconsistent with its design and intended purpose.

See id.

at 756.

The “FOR RECREATIONAL USE ONLY” warning placed inside the Splash Rower packaging constituted an adequate warning because it alerted the Respondent about potential dangers, explained the potential causes of injuries, and provided instructions to safely use the product. See Gray v. Badger Mining Corp.

, 676 N.W.2d 268, 274 (Minn. 2004). Vortex’s warning indicated the product was designed only for recreational use, explained injury might

25

result if these limitations were exceeded, and instructed the Respondent to use the product only for recreational purposes. See id.

Vortex’s warnings were adequate because they advised against the specific conduct the Respondent was engaged in at the time of injury. See Parish v. Jumpking , Inc.

, 719

N.W.2d 540, 546-47 (Iowa 2006). For instance, the court in Parish , where the plaintiff broke his neck while performing a flip on a trampoline, held that the defendant’s warnings specifically advising against flips constituted adequate warnings. Id . The court held no reasonable trier of fact could find the warnings inadequate, and granted summary judgment.

Id .

As in Parish , the Respondent injured herself using the Splash Rower for non-recreational purposes counter to the specific warning stating “FOR RECREATIONAL USE ONLY”. See id . Like the plaintiff in Parish , who knowingly did flips on the trampoline after seeing all of the defendant’s warnings, the Respondent’s attempted twenty-mile route down the Crawford

River exceeded the recreational purpose of the Splash Rower, counter to Vortex’s warnings.

See id.

The Respondent engaged in activities specifically warned against, thus this court should find the warnings adequate. See id. Because adequate warnings were placed on the

Splash Rower, Vortex is entitled to summary judgment on the Respondent’s failure to warn claim. See Paris , 719 N.W.2d at 547; Craw. R.C. §895.52.

The dangers presented by the Crawford River were open and obvious, eliminating

Vortex’s liability for failing to warn. See Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. j

(1998). Mr. Roger Sullivan’s testimony indicates that a casual observer would notice the

Crawford River required an experienced guide to assist with maneuvering around the river’s dangerous obstacles and narrow passages. Even if this court chooses not to admit Mr.

Sullivan’s expert testimony, the respondent should still have seen that the high water and the

26

conditions were dangerous. Additionally, the respondent should have scouted her twenty-mile route as suggested by the International Scale of River Difficulty . See Safety Code of American

Whitewater , A

MERICAN

W

HITEWATER

, http://www.americanwhitewater.org/ content/Wiki/safety:start?#vi (last visited Mar. 7, 2012, 7:30 PM). The respondent knew heavy rains and thunderstorms passed through the area the weekend prior and ignored the conditions, breaking the causal chain. Bates , No. 10-CV-9568.

The conditions of the river were open and obvious to the Respondent because the casual observer would notice the narrow passages and excessive rocks, thus Vortex is not subject to liability. See Blue , 828 N.E.2d at 1144; Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. §

2 cmt. j (1998). For example, in Blue , where the plaintiff placed his foot inside a running trash compactor and suffered injuries, the court held that no duty to warn existed because the danger of the functioning trash compactor was open and obvious. 828 N.E.2d at 1134, 1144.

The court applied the Restatement (Third) of Torts and found that it is typically fruitless to provide a warning when the danger is open and obvious because a warning does not ensure safety or compliance. Id.

at 1144. Because of the fruitless nature of such warnings, Vortex does not need to indicate that the Splash Rower should not be used for a non-recreational purpose on a river with strong currents, rocks, and narrow passages. See id.

The Respondent failed to meet her burden of proof for her failure to warn claim because she did not establish Vortex’s failure to warn was the proximate cause of her injury.

Bates , No. 10-CV-9568.

The Respondent had minimal kayaking experience, and no kayaking experience since her injury. Mr. Sullivan testified that he would strongly discourage a person in limited physical condition from rafting on the Crawford River. The Crawford River clearly exceeds recreational limits when viewed in light of Mr. Sullivan’s testimony that the

27

Crawford River is “highly dangerous”, and “notorious for the amount of rocks”. See id.

Kayaking down the Crawford River following heavy rains exceeded the Respondent’s training, experience, and the Splash Rower’s intended use, preventing the establishment of any failure to warn as being the “but for” cause of her injury. See id. The failure to stay within her experience level breaks her causal chain because it, not a failure to warn, was the “but for” cause of her injury. See id.

The Respondent’s injury would have been prevented had she heeded the package warnings about the Splash Rower’s intended use. See Moore , 332 S.W. at

763.

This court should grant Vortex’s motion for summary judgment because Vortex provided an adequate warning as to the foreseeable risks of harm. Celotex Corp.

, 477 U.S. at

322-23; Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2(c) (1998). The Respondent failed to heed Vortex’s warning and the risks of harm posed by the river were open and obvious. See

Moore , 332 S.W.3d at 757; Parish , 719 N.W.2d at 546-47. The Respondent’s use of the

Splash Rower in a manner inconsistent with its design and intended purpose, and her failure to heed the warning about the specific conduct that caused her injury, establishes that Vortex’s warning was adequate. See Moore , 332 S.W.3d at 757; Parish , 719 N.W.2d at 546-47.

Additionally, the risks were open and obvious, thus eliminating Vortex’s liability to warn, as warnings for general obvious dangers are likely to be ignored. See Blue , 828 N.E.2d at 1144;

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Prods. Liab. § 2 cmt. j (1998). Thus, Vortex’s adequate warning, and the open and obvious dangers of the Crawford River compels the court to grant summary judgment for Vortex.

See Blue , 828 N.E.2d at 1144 .

28

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Vortex Recreational Systems, Petitioner, respectfully requests this Honorable court grant Vortex’s motion for summary judgment on all of the

Respondent’s product liability claims.

Respectfully submitted by,

Vortex Recreational Systems

29

APPENDIX FOR THE PETITIONER

30

Vortex Recreational Systems

Splash Rower Product

MATERIALS TESTING REPORT

Michael Robinson Dr.

Gregory Scott Crawford

Tech University

November 30, 2009

31

Background:

• Vortex Recreational Systems is developing a new product called the Splash Rower.

• Vortex Recreational Systems is seeking materials testing on the Splash Rower.

• Vortex Recreational Systems has hired Crawford Tech University student Michael

Robinson to conduct such materials testing.

• Michael Robinson’s work is under the supervision of Crawford Tech University

Professor Dr. Gregory Scott.

Objective:

•

To determine whether a Splash Rower made from graphite materials is as strong against the force of water current as a Splash Rower made from iron materials.

•

Test Materials:

•

Motorized lap pool

• 2 standard prosthetic arms

• 2 wooden stands

• 1 standard paddle

•

30 graphite Splash Rowers

•

30 iron Splash Rowers

Test Parameters:

• Test time per test run: 10 minutes with the water flowing against the submerged paddle;

10 minutes with the water flowing from behind the submerged paddle.

•

Test 10 graphite Splash Rowers and 10 iron Splash Rowers at each speed:

Slow: 3 mph; Medium: 7 mph; Fast: 10 mph.

Categorize each test run result: (1) remained attached with no physical change; (2) remained attached with a cracked or bent shape; or (3) snapped apart.

Results:

Test Results for IRON Vortex Splash Rower:

3 mph (low)

7 mph

(medium)

10 mph

(high)

Remained Attached (No Physical

Change)

10

10

10

Remained Attached (Cracked or

Bent

Shape) 0

0

0

Snapped

Apart

0

0

0

32

Test Results for GRAPHITE Vortex Splash Rower:

3 mph (low)

7 mph

(medium)

10 mph

(high)

Remained Attached (No Physical

Change)

10

10

8

Remained Attached (Cracked or

Bent

Shape)

2 (bent slightly)

GRAPHITE)Vortex)Splash)Rower

!

!

12!

!

!

!

10!

!

!

!

8!

!

!

3!mph!(l!ow)!

6!!

0

0

Snapped

Apart

0

0

0

7!mph!(medium)!

!

10!mph!(hig!h)!

4!

!

!

!

2!

!

!

!

0!

Remained!Atta!ched!(No!

Physical!Cha!nge)!

!

Remained!Atta!ched!

(Cracked!or!Bent!Shape)!

!

Sna!pped!Apart!

33

IRON Vortex Splash Rower

12

10

8

6

3 mph (low)

4

7 mph (medium)

10 mph (high)

2

0

Remained Atta ched (No

Physical

Change)

Remained Atta ched

(Cracked or Bent Shape)

Sna pped Apart

Conclusions:

• Clearly, graphite Splash Rowers are just as adequate as iron Splash Rowers at

Low and

Medium speeds.

•

In general, graphite Splash Rowers preformed just as strongly as iron Splash

Rowers even at High speed.

• Slight physical alterations of 2 graphite Splash Rowers occurred at High Speed, but this result may be more indicative of graphite’s flexibility.

34

Affidavit of Roger Sullivan on Behalf of Defendant Vortex Recreational Systems

My name is Roger Sullivan and I have been a rafting guide in Crawford for fifteen years. I currently own and operate a rafting guide service located in St. Martin, Crawford, which is a small town located to the west of the City of Wells along the Crawford River. I have expert knowledge of the Crawford River based on guiding hundreds of rafting trips on the river and personally rafting the river for over thirty years.

The Crawford River is a Class III river that is a major attraction for rafting enthusiasts.

A Class III grade indicates that the Crawford River has a rating of Difficult. On a Class III river, a rafter can expect numerous waves that are often high and irregular. A rafter can also expect to encounter rocks and other obstacles. The Crawford River is notorious for the amount of rocks that are found clustered together throughout the river. A majority of the rocks are not visible from the surface which presents a danger for rafters in shallow water and those rafters that find themselves tossed from a raft.

The Crawford River is also known for its narrow passages where a rafter can experience the greatest speeds and most challenging rapids. Under normal conditions, the Crawford River flows between 8 and 12 miles per hour (mph). However, washout from heavy rains and high winds can cause the river to flow up to a speed of almost 20 mph. Based on my experience, only the most experienced rafters are capable of navigating their way down the Crawford River.

Furthermore, in my opinion, a casual observer would see the Crawford River for the first time and know that an experienced guide is needed to assist rafters with maneuvering around the river’s dangerous obstacles and through its narrow passages.

All the rafters I take out on the Crawford River are required to wear a helmet and life jacket and I only use professional grade rafting equipment. However, sometimes even the best safety gear and equipment cannot prevent an injury from rafting on the Crawford River.

Strong currents can cause even experienced rafters to lose control of their raft and equipment or toss them from the raft into the water. The river currents can also hold tossed rafters under water for a period of time with little protection from the surrounding rocks.

Rafting the Crawford River is also a challenge physically. Rafters should be at full strength and health before attempting to go rafting. I would strongly discourage any rafter with a health problem or in a limited physical condition from attempting to raft the Crawford River.

All in all, the Crawford River can be highly dangerous and should not be taken lightly by rafting enthusiasts.

I attest that everything I have stated in this affidavit is true and accurate to the best of my knowledge.

Roger Sullivan

9/10/10

Roger Sullivan

35

State of Crawford Statutes

Craw. R. Evid. 98 – Standard of Review, Appeal of Summary Judgment

Whether before an Appellate Court of this State or the Supreme Court of this State, any appealed order granting summary judgment pursuant to Crawford Rule of Civil Procedure 56 is reviewed de novo.

Craw. R. Evid. 905 –Expert Testimony

(a) The provisions of this Code section shall apply in all civil actions.

(b) If scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will assist the trier of fact in any cause of action to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue, a witness qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify thereto in the form of an opinion or otherwise, if:

(1) the testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data which are or will be admitted into evidence at the hearing or trial;

(2) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

(3) the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case. (c) An affiant must meet the requirements of this Code section in order to be deemed qualified to testify as an expert by means of an affidavit.

(d) In order for a scientific report or study to be given the weight of expert opinion with respect to the report’s or study’s proffered scientific findings, the author of such report or study must meet the requirements of this Code section.

(e) It is the intent of the legislature that, in all civil cases, the courts of the State of

Crawford not be viewed as open to expert evidence that would not be admissible in other states. Therefore, in interpreting and applying this Code section, the courts of this state may draw from the opinions of the United States Supreme Court in Daubert v. Merrell

Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

, 509 U.S. 579 (1993); General Electric Co. v. Joiner , 522 U.S.

136 (1997); Kumho Tire Co. Ltd. v. Carmichael , 526 U.S. 137 (1999); and other cases in federal courts applying the standards announced by the United States Supreme Court in these cases.

(f) Whether before an Appellate Court of this State or the Supreme Court of this State, the standard of review for the admission of any evidence under this Code section shall be an abuse of discretion standard.

36

Craw. R.C. § 5255 – Crawford Product Liability Act (amended 2008)

(a) This Code section shall be solely governed by the Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products

Liability (1998).

(b) When a question of legal interpretation arises under this section with respect to a question of law for which the Supreme Court of this State has not provided an applicable legal standard, the courts of this State may rely on decisions rendered by the highest court of any other state on such question of law.

(c) Any decision relied on by a court of this State under subsection (b) shall be treated as solely persuasive authority and shall not be controlling in any case.

Craw. R.C. § 895.52 – Recreational activities; limitation of property owner’s liability. (1) D EFINITIONS . In this section:

*** (intentionally omitted) ***

(g) "Recreational activity" means any outdoor activity undertaken for the purpose of exercise, relaxation or pleasure, including practice or instruction in any such activity.

"Recreational activity" includes hunting, fishing, trapping, camping, picnicking, exploring caves, nature study, bicycling, horseback riding, bird-watching, motorcycling, operating an all-terrain vehicle, ballooning, hang gliding, hiking, tobogganing, sledding, sleigh riding, snowmobiling, skiing, skating, water sports, sight-seeing, rock-climbing, cutting or removing wood, climbing observation towers, animal training, harvesting the products of nature, sport shooting and any other outdoor sport, game or educational activity.

"Recreational activity" does not include any organized team sport activity sponsored by the owner of the property on which the activity takes place.

*** (intentionally omitted) ***

(2) N O DUTY ; IMMUNITY FROM LIABILITY .

(a) No owner and no officer, employee or agent of an owner owes to any person who enters the owner's property to engage in a recreational activity:

1. A duty to keep the property safe for recreational activities.

2. A duty to inspect the property, except as provided under s.

3. A duty to give warning of an unsafe condition, use or activity on the property.

37

(b) No owner and no officer, employee or agent of an owner is liable for the death of, any injury to, or any death or injury caused by, a person engaging in a recreational activity on the owner's property or for any death or injury resulting from an attack by a wild animal.

*** (intentionally omitted) ***

(7) N

O DUTY OR LIABILITY CREATED

. Except as expressly provided in this section, nothing in this section or the common law attractive nuisance doctrine creates any duty of care or ground of liability toward any person who uses another's property for a recreational activity.

(8) Nothing in this section shall be construed as preventing a person from being held liable under

§ 5255 of this Code.

38

39