Answers - University of Western Ontario

advertisement

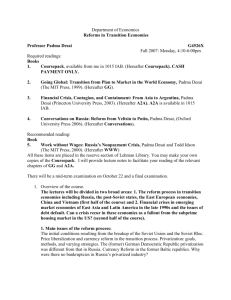

The University of Western Ontario Faculty of Information and Media Studies MIT 256F Popular Culture and Identity Midterm Exam Answers WARNING: The following answers are incomplete. All I have provided for Part 1 is the author and the page number of where the quotation is taken from. For Part 2, the answers I have given are also brief, but they contain the main points, which need to be expanded upon. PART 1: C ITE PASSAGE (15 M ARKS T OTAL ) For each of the following five questions you are required to identify the author of the quoted passage, explain the passage and how it fits into the whole of the paper, with reference to the thesis if possible. (3 marks each) Q1. “To be someone’s friend is to undertake weight responsibilities and obligations that at times may limit your own freedom. The same is true, obviously, of family. And to a large extent, the same is true of involvement with religious institutions. Most religious institutions call on their members to live their lives in a certain way and to take responsibility for the well-being of their fellow congregants.” A1. Barry Schwartz, p. 107. (Coursepack, p. 73) Q2. “So much can I desire this, that I may, in my bitter longing for status, prefer to be bullied and misgoverned by some member of my own race or social class, by whom I am, nevertheless, recognised as a man and a rival—that is, as an equal—to being well and tolerantly treated by someone from some higher and remoter group, someone who does not recognise me for what I wish to feel myself to be.” A2. Isaiah Berlin, p. 157. (Coursepack, p. 20) Q3. “When someone complains—as do some of those who attempt or commit suicide—that his or her life is meaningless, he or she is often and perhaps characteristically complaining that the narrative of their life has become unintelligible to them, that it lacks any point, any movement towards a climax or a telos. Hence the point of doing any one thing rather than another at crucial junctures in their lives seem to such a person to have been lost.” A3. Alasdair MacIntyre, p. 139. (Coursepack, p. 52) Q4. “Those capitalists who are not dizzily rich are forced to invest their capital or sell their labor power. So they have an alternative to selling their labor power which the worker lacks. But they are not gods. Like the worker, they ‘enter into relations that are indispensable and independent of their will.’ ” A4. G. A. Cohen, p. 21–22. (Coursepack, p. 38) 2 Q5. “A child who is consistently cast as ‘nurse’ in playground games can come to accept that identity as ideal, making it formative in her general behaviour, first playing and then becoming solicitous. But despite always being lured into playing the nurse’s role, a child might subjectively appropriate the ideal of a swashbuckling adventurer and attempt to graft bold, daring traits on the manner of her playing nurse. While such improvisatory grafts are often fruitful, they can also generate erratic or conflicted behaviour.” A5. Rorty and Wong, p. 24. (Coursepack, p. 62) PART 2: Q UESTIONS (21 M ARKS ) Answer all seven of the following questions. (3 marks each) Q1. According to Berlin, why is it wrong to lie to other human beings? A1. It is wrong to lie because lying involves (1) using other people as means to one’s own ends, thereby (2) preventing others from making decisions for themselves. And that is wrong because (3) making decisions for oneself and deciding what to value for oneself is the essence of being human, and (4) human beings are the ultimate sources of value. . . . to lie to men, or to deceive them, that is, to use them as means for my, not their own, independently conceived ends, even if it is for their benefit, is, in effect, to treat them as sub-human, to behave as if their ends are less ultimate and sacred than my own. (Berlin, p. 137; Coursepack, p. 10) Q2. Explain why Berlin thinks that asceticism (being a Stoic or a ‘rational sage’) can be an ideal of positive liberty, and why he thinks there is something wrong with this. A2. Being an ascetic can be an ideal for positive liberty because (1) positive liberty states that one is free if one is free from internal obstacles such as desires and so on and (2) since being ascetic means being free from as many desires as possible(including the desire to be free from pain), being ascetic could be thought of as a goal of positive liberty. This is bad because this would imply (1) that one could be free no matter how bad the political situation is, even if people are torturing you. (2) This kind of ‘ascetic’ freedom isn’t really freedom; it is better described as integrity or self-control. Most absurdly, one becomes ultimately free by dying. The doctrine that maintains that what I cannot have I must teach myself not to desire; that a desire eliminated, or successfully resisted is as good as a desire satisfied, is a sublime, but it seems to me, unmistakable, form of the doctrine of sour grapes: what I cannot be sure of, I cannot truly want. . . . Ascetic self-denial may be a source of integrity or serentity and spiritual strength, but it is difficult to see how it can be called an enlargement of liberty. . . . The logical culmination of the process of destroying everything through which I can possibly be wounded is suicide. (Berlin, p. 139–140; Coursepack, p. 11–12) Q3. What three factors does Cohen give to explain why there are still exit options from the proletariat? A3. The three factors that explain why there are still exit options: (1) taking an exit option, such as becoming a member of the petty bourgeoisie, is very hard work, and not everyone wants 3 to do what is hard; (2) members of the proletariat come to believe that this is an inescapable fact of their life; and (3) solidarity: not everyone in the proletariat wants to leave that life behind if there are still others who are there. (Cohen, p. 13; Coursepack, p. 34.) Q4. Explain how people can be individually free and be collectively unfree at the same time. A4. A group of people can be individually free, if there remain options to escape. But if the number of options is fewer than the number of people, then that group is collectively unfree since not all can leave at the same time. So long as an option to escape remains, each member of that group remains free. Q5. According to MacIntyre, what are the two main crucial characteristics necessary for all lived narratives? Explain them. A5. The two main crucial characteristics are (1) unpredictability and (2) teleology. This unpredictability coexists with a second crucial characteristic of all lived narratives, a certain teleological character. . . . There is no present which is not informed by some image of some future and an image of the future which always presents itself in the form of a telos – or of a variety of ends or goals – towards which we are either moving or failing to move as part of our lives. (MacIntyre, p. 137; Coursepack, p. 51) Q6. According to Rorty and Wong, what are the five main sources of identity? Give a brief explanation of each. A6. (1) Somatic, proprioceptive, and kinaesthetic dispositions, (2) Central temperamental or psychological traits, (3) Social role identity, (4) Socially defined group identity, and (5) Ideal identity. (Rorty and Wong, p. 21–23; Coursepack, p. 60–61) Q7. Schwartz cites a poll indicating a rising feeling of helplessness in America as their ability to choose continues to increase. What two possible explanations does Schwartz offer to explain this paradox? A7. (1) “[A]s experience of choice and control gets broader and deeper, expectations about choice and control may rise to match that experience. . . . aspirations and expectations about control speed ahead of their realization. . . ” (2) “[M]ore choice may not always mean more control. Perhaps there comes a point at which opportunities become so numerous that we feel overwhelmed. Instead of feeling in control, we feel unable to cope.” (Schwartz, p. 103–104; Coursepack, p. 71–72)