two 'visions', one democracy

advertisement

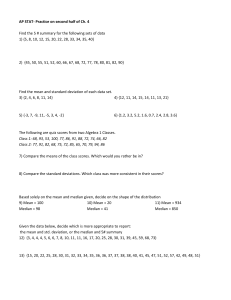

TWO ‘VISIONS’, ONE DEMOCRACY: DO ‘MAJORITARIANISM’ AND ‘PROPORTIONALITY’ SIMULTANEOUSLY GUIDE DEMOCRATIC POLICY-MAKING? Ian Budge* University of Essex Colchester, UK Email: budgi@essex.ac.uk *corresponding author Michael D. McDonald Binghamton University SUNY Binghamton, NY, USA mdmcd@binghamton.edu 2 TWO ‘VISIONS’, ONE DEMOCRACY: DO ‘MAJORITARIANISM’ AND ‘PROPORTIONALITY’ SIMULTANEOUSLY GUIDE DEMOCRATIC POLICY-MAKING? ABSTRACT Democracy is supposed to effect the popular will. But is this best expressed by the party with the largest vote or by compromise among all parties? Median-sensitive ‘proportionality’ as opposed to plurality-based ‘majoritarianism’ has been seen as distinguishing ‘proportional democracies’ from ‘majoritarian democracies’. Both however have representational claims which can be made within any one democracy. Dilemmas about which ‘vision’ to follow are in practice eased by joint participation of plurality and median parties in government – but even more by their policy preferences generally pointing in the same direction anyway, facilitating a common response in terms of government policy. This article examines policy relationships between plurality parties, median parties and governments inside 16 post-war democracies, uncovering practical bases for accommodation between ‘majoritarian’ and ‘proportional’ visions. 3 TWO ‘VISIONS’, ONE DEMOCRACY: DO ‘MAJORITARIANISM’ AND ‘PROPORTIONALITY’ SIMULTANEOUSLY GUIDE DEMOCRATIC POLICY-MAKING? THE POPULAR WILL: MAJORITARIAN, PROPORTIONAL – OR BOTH? Classical political theorists assumed that the popular will emerges unproblematically from general discussion and voting (Schattschneider, 1942, 14). The actual failure of elections to produce clear majorities has long been known – less than 10 per cent do (McDonald & Budge, 2005, 22-3). However, it took Bingham Powell’s seminal exploration of ‘Elections as Instruments of Democracy’ (2000), to focus scholarly attention on the consequences of such failure.. These lead in most democracies to manufacturing the missing majority through election rules which give the plurality party (with the largest individual vote) a majority of Parliamentary seats: or to creating a majority through legislative negotiations between potential coalition partners which will then form a government. These procedures were put on an equal footing in Powell’s ‘two visions of democracy’. Election systems which habitually produced a clear mandate for one party were characterized as ‘majoritarian democracies’ and multi-party systems with coalition governments as ‘proportional democracies’. While the first had obvious advantages of coherence and accountability, proportional democracies – in line with Lijphart’s (1968, 1984, 1999) arguments for consensus and negotiation – produced greater policy congruence between citizens and governments. Powell (2000, 77-81) notes that single party governments usually rest on plurality votes rather than genuine electoral majorities. The government majority is purely legislative, created by the tendency of single member constituency systems with plurality winners (SMDP) to translate a popular plurality into a legislative majority. However, the ready identifiability of the plurality winner and the mandate conferred by plurality status justify the procedure. Where no party is clearly identified by the election as the leading contender, 4 coalition negotiations and policy compromises are necessary to produce a government. This, as a matter of fact, often takes policy stands closer to those of the median citizen than does a plurality-based one (Powell, 2000, 221-2). What emerges are two distinct types of modern democracy which work in different ways and produce rather different results. McDonald et al (2004) seek to bridge this gap by presenting a unified account of democracy at work in their theory of the median mandate (see also McDonald & Budge, 2005). Their argument is that elections can be seen as expressing a majority preference indicated by the position of the median voter. All democracies, in order to qualify as such, have to make ‘a necessary connection between acts of governance and the equally weighted felt interests of citizens with respect to these acts’ (May, 1978: Saward, 1998, 51). Thus ‘majoritarian’ as well as ‘proportional’ democracies ought to bring government policy as close as possible to the median voters preference and can all be assessed on their ability to do so. On this comparison, proportional systems perform better than majoritarian or plurality ones (confirming Powell, 2000, 221-2 – who however did not so explicitly set up conformity to the median preference as a general standard). The median mandate approach has a consistent logic behind it, which given its premises seem to provide both the desired unified approach to democracy and a rationale for Lijphart’s advocacy of ‘consensus democracy’ - and incidentally for Powell’s findings in favour of proportional democracy. The premises the median mandate thesis rests on are however very strong and probably unrealistic. In particular it assumes that all voters decide between parties on policy grounds. This surely flies in the face of evidence from voting studies from all over the world in the tradition of The American Voter (Campbell et al, 1960). Even if we learned nothing else from these, they conclusively demonstrate that party attachments, government competence, candidate appeals and many situational factors apart from issues have a strong – even major – influence on the popular vote. If we allow for an electorate that votes with mixed motives, not just in terms of policy (or even more narrowly, in terms of policy proximity) we have got to step back towards Powell’s position and reconsider the conflicting claims of the plurality voter and the median 5 voter to represent majority opinion. We are not going back entirely to Powell however as recent evidence suggests that both plurality-based majoritarianism and proportionality can be seen as entering into electoral and governmental processes in all democracies, not just as distinguishing one type of democracy from another. This evidence comes from a series of studies (Wlezien, 1996: Wlezien & Soroka, 2009: Soroka & Wlezien, 2004: 2005) of the ‘majoritarian’ democracies of Britain, Canada and the US, which show government policy initiatives as extremely sensitive to movements of public opinion. Such movements are often based on an adverse reaction of electors to the proposed policies themselves, which the government then modifies to improve its standing in the next election. The Macro Polity (Erikson, MacKuen & Stimson, 2002, 282-326) also sees these ‘thermostatic’ interplays as being at work between US elections. If plurality parties in these ‘majoritarian’ democracies habitually accommodate public opinion (representing in part the other parties’ policy preferences) then clearly some kind of ‘proportional’ negotiation and compromise with other political groupings is taking place. The US of course is well known for the continuing negotiations and policy compromises which the division of powers forces on all parties. Canada has frequent minority governments whose survival depends on effective compromise. Wlezien & Soroka’s evidence demonstrates however that even Britain’s ‘elective dictatorship’ cannot simply steamroll its policies through and has to take opposition into account. This is hardly surprising – even elective dictatorships have to concern themselves with votes in the next election. But the findings indicate that ‘majoritarianism’ can and does co-exist with ‘proportionality’, rather than substituting for it as an exclusive form of decisionmaking in one democracy as opposed to another. On the other side evidence from proportional systems indicates that plurality status gives parties considerable advantages over the others they negotiate with in the formation of coalition governments (Muller & Strøm, 2000), share of cabinet seats (Browne & Franklin, 1973) and policy-making (see below). Quite apart from the detailed evidence one can recognise generally that in the absence of an electoral majority, both the largest party and all the parties have claims to 6 represent the popular will. In the absence of any clear criterion to decide between their claims, surely most democracies have to try to accommodate both, at any rate to some extent. Below we check comparative evidence to see to what extent they can be, and are, mutually accommodated. First however we have to consider how to identify the carriers of the majoritarian and proportional ‘visions’ in practice. We argue below that the plurality party is the one with the commanding numerical basis whether in a multi-party legislature or in one where SMDP gives it the majority of seats. It thus represents the concept of majoritarianism in democratic decision-making. The median party position is the one that would probably be arrived at by all-party negotiation and compromise. It thus embodies the concept of proportionality. OPERATIONALISING MAJORITARIANISM AND PROPORTIONALITY: PLURALITIES AND MEDIANS. Since Downs (1957) and Black (1948, 1958) independently demonstrated the ‘Power of the Median’, the median position on a one-dimensional policy continuum (usually the overarching Left-Right dimension) has generally been taken to represent the popular preference (cf Powell, 2000, 175-229: Adams et al 2004: Ezrow, 2005). From Figure 1 it is easy to see why. If all actors prefer positions closer to their own [FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE] to ones further away they will not leapfrog to form majority coalitions with actors on the other extreme (A with G for example). A would always prefer to be in the majority ABCDE. Similarly G would always prefer the combination GFE to any other majority. These preferences make E, at the median, crucial in deciding which majority will form, as it is essential to both. E is also assumed to be policy-motivated so will favour the majority which adopts the policy position closest to its own. Successive bargaining rounds will thus end up with a majority position close to that of the median. Hence the median position is the one which proportional bargaining and negotiation between all parties will produce as the majority preference. 7 The logic is very strong – if the assumptions on which it is based are appropriate. That is to say, it will only hold if all the actors are purely policy-motivated and if they array all their policy-preferences along a one-dimensional continuum, as shown in Figure 1. In practice the only cleavage which could sustain such an overarching policy continuum is LeftRight. Figure 1 probably gives a good picture of the way legislative voting proceeds if we take the percentage distribution as referring to shares of Parliamentary seats. Parties do seem to divide along Left-Right lines and favour positions closer to their own (Axelrod, 1970 165-85: Budge et al 2001, 20-45). Even at legislative level however other considerations may enter. Where policies far removed from Left-Right concerns are voted on separately they may produce a different ordering of the parties. Moreover a legislature may have nonpolicy-based concerns about having stable and effective government in the face of external threats and crises which would favour having a large plurality party as its basis. The Nordic countries are a good case in point where the social democrats have often been favoured in government formation through being the single largest party. Even in a multi-party legislative situation therefore considerations other than LeftRight policy positions may surface, favouring a large plurality party over the Left-Right median position. This is even truer and more relevant at electoral level when we take the percentage distribution in Figure 1 as referring to election votes. General Elections put voters in the position of having to express both policy preferences and choose a government at the same time. Some votes therefore will inevitably be cast on non-policy based considerations – which may even sway a majority of voters. When the dominant concern can often be government effectiveness, stability, and clear accountability, there is then considerable justification for the tendency of the SMDP rules to translate a popular plurality into a majority of legislative seats. Even when we try to evaluatet the vote distribution in pure policy terms, the seeming median party which emerges from it may not actually be at the genuine median policy position. This discrepancy would occur if any vote was affected by non-policy 8 considerations. In that case discounting non-policy votes could lead to the seeming median being displaced to Left or Right. Given uncertainty about the median’s true position, voters for the plurality party might well claim to bestow a more convincing policy mandate by arguing that their votes had more policy content than the others. However, the median position cannot be totally written off as uninformative, even where the legislative majority goes to the plurality party. The distribution of votes emerging from the General Election is the most authoritative expression of overall policy preferences that we have, even if we have some doubts about it. Under the declared distribution of preferences the revealed median is the only one common to all vote-based majorities. The median position therefore is the one such majorities would tend to endorse after any process of negotiation. This means that the median position emanates from the preferences of all electors, not just from one (perhaps extreme) group, as might be the case with the plurality position. This is particularly true as it is the declared preference which is closest in aggregate to all declared individual preferences and thus minimizes dissatisfaction if adopted. These considerations all lend the median position some standing even where SMDP rules give the popular plurality the legislative majority. Arguments about the popular majority basis of the median and the plurality positions can go on endlessly however as we lack the crucial information about what mix of motivation went into the votes and whether therefore the median is the ‘real’ policy median or the plurality party is the ‘real’ policy majority. Their contrasting claims are summarized in Table 1. [Table 1 about here] What the Table makes clear is that neither the median nor the plurality positions can be decisively dismissed as carriers of the popular majority preference under representative democracy. The median position is the one that would probably be arrived at by party negotiation and compromise and thus operationalizes the concept of ‘proportionality’ in democratic decision-making. The plurality position is the one with a commanding numerical 9 basis whether in a multi-party legislature or in one where SMDP gives it the majority of seats. It thus represents the concept of majoritarianism in democratic decision-making. Does this – given the claims of median-based proportionality – always prevail however, even in democracies we would regard as generally majoritarian? And does plurality-based majoritarianism always lose its force even where decision-making is more proportional? (in practice under coalition Governments under PR with multi-parties). Now that we have investigated the general claims for representing the popular majority that can be made on both sides we can examine actual democratic practices empirically and comparatively, by seeing how government formation and policy-making respond to ‘proportional’ median and ‘majoritarian’ plurality preferences in 16 post-war democracies. GOVERNMENT FORMATION AND COMPOSITION We take our information about government composition from Woldendorp, Keman and Budge (2000) and use the vote distributions reported in Volkens, Schnapp & Lass (1992) with updates to 1995, our end year, from the specialist reports in the European Journal of Political Research. To characterize the party supported by the median voter we additionally rely on the Comparative Manifesto Project’s (CMP) Left-Right scorings of parties in the 16 democracies for each post-war election 1945-1995 (Budge et al, 2001, 19-46). Details of how the Left-Right scale has been constructed are given below when we come to analyse party policy positions more directly. Here we concentrate on government formation as such, against the background of the election results and the declared preferences of electors for the parties’ overarching positions on the left-right scale. Table 2 reports the relative and absolute frequencies of being in government [Table 2 about here] or not, for the plurality and median electoral parties, for the first governments forming immediately after each of 215 elections – covering sixteen nations from the early 1950s through 1995 (not including France’s government after its unique PR election, in 1986). The 10 fourfold classification shows whether the median electoral party, 1 the plurality electoral party, both, or neither are in government. The top cross-classification covers all nations; the two tables underneath separate out elections conducted under SMDP rules (N = 81) from those conducted under PR (N = 135).2 The main message of the sixteen-nation cross-classification is that the plurality party holds a privileged position. It is included in about four out of five governments. The party closest to the median voter (i.e., the electoral median party) holds office in just under twothirds of these first governments after an election3 and most of those cases are situations when the plurality party is also in government – 122 out of 140 cases. Going one step further, of these 122 cases, ninety five are situations when one party is both the plurality and median. The conjunction of median voter and plurality voter endorsement all but guarantees inclusion in government. All ninety-five times it occurs, the party is in office. But, when one but not the other is included, the plurality party is three times more likely than the electoral median party to be there. The cross-classifications for SMDP and PR systems are remarkably similar. The marginal relative frequencies are virtually the same – including the median party in about 65% of governments while including the plurality party in about 85% of governments under SMDP and 79% under PR (not a statistically significant difference). A more notable difference comes from PR systems’ slightly greater tendency to include the median party in a government when it does not also include the plurality party. By implication, these governments display a slightly lesser tendency to include the plurality party, and a slightly lesser tendency to include both the median and plurality. This difference, we suppose, 1 A median electoral party is the party with a Left-Right score closest to the position of the median voter. This may or may not be the same as the median parliamentary party as such. For the calculation of the Left-Right score see below. 2 Elections in six nations are classified as SMDP: Australia, Canada, France Fifth Republic (excluding 1986), New Zealand (its post-1995 mixed-PR elections are not in the data set), the United Kingdom, and the United States (presidential elections). 3 The two-thirds fraction is lower than the three-fourths reported in Müller and Strøm, (2000, 564). Part of the difference relates to the fact that we are dealing with the median electoral party and not the median parliamentary party; part relates to coverage of different nations; and part, in comparison to Müller and Strøm, relates to Left-Right party locations based on expert survey data versus the MRG-CMP data used here. 11 comes from SMDP elections encouraging voting that attaches the median and plurality designation to the same party – 58% of elections under SMDPs (with Britain and France the notable exceptions) versus 36% of elections under PR.4 Going back to our general concerns, the main point that emerges from comparing government participation is surely the absence of any real difference between proportional and majoritarian (SMDP) systems in privileging the plurality over median as the expression of majority support. Certainly there remains a difference between the systems - which we investigate below for its policy effects – in terms of whether the plurality party is the leading or the only member of the government. In terms of the policy centrality accorded to the median and plurality parties there does however seem little difference in democratic practice across the board. All democracies seem ‘majoritarian’ rather than ‘proportional’ in emphasis, so far as government formation and confrontation are concerned. DOES PLURALITY VS MEDIAN ENDORSEMENT MAKE A DIFFERENCE IN POLICY TERMS? Features of government beyond the inclusion of particular types of parties are important to governing positions. Perhaps, for example, the electoral plurality party tends more often to go it alone in government, whereas the electoral median party tends to join in a coalition. If so, the electoral plurality party would have more weight in policy-making than the numbers on its presence or absence indicate by themselves. Alternatively, when the plurality and median parties are not one and the same, they may take similar policy positions, and thus a seemingly clear-cut distinction in terms of relative government participation is not vastly important in terms of the policy being adopted. In addition to taking account of party characteristics, the fact that median and plurality voter positions are correlated has to be considered. The correlation is not a necessary (definitional) matter. But logic tells us that it is likely to emerge empirically. On the ‘not 4 There is a tendency for the plurality voter party to gain advantage from having a vote percentage approaching 50 and for the median to gain an advantage from a close vote split between the two largest parties. We do not pursue more detailed analyses of those tendencies, as such pursuit is more likely to cloud than to make clear the main message that a plurality voter’s preferred party is relatively privileged in comparison to a median voter’s preferred party. 12 necessarily so’ side of various possibilities, imagine a right-leaning party at the next election. Imagine also, because its vote splits with another right wing party, that the right-leaning party loses its plurality status to a party on the left. This combination of changes has the median voter moving rightward (the Right vote increases in total) while the plurality party moves leftward. On the correlated side of the possibilities, however, imagine that a right-leaning party in a two-party system loses one election by a 45-55 voter percentage split and wins the next election by a 54-46 split. The median voter moves to the Right between these elections and so does the plurality voter. As party systems generally remain stable between successive elections we suspect that the correlated movements predominate. But this needs further investigation. One clear relationship does emerge however. If support for the party alternatives remains broadly the same from election to election, a marginal shift in the plurality voter position will go in the same direction as a shift in the median position. We examine the practical possibilities for co-ordinated movement between the two in policy terms, using a Left-Right measure. We are not bound to the idea that all of policy is necessarily contained in the Left-Right distinction. However, for a comparative analysis such as this it is the one type of conflict which crops up in all countries and time periods, rendering it possible to place all parties, wherever located, within the same policy framework (Budge, Robertson & Hearl eds, 1987: Huber & Inglehart, 1995: Klingemann et al, 2006). Possibly because of the universality of the Left-Right cleavage, there is the further constraint on our investigation that the only measure on which one can trace party policy movement over time, in a number of countries, is the Left-Right scale devised by the Manifesto Research Group/Comparative Manifestos Project (MRG-CMP) (Klingemann et al, 2006, 5-9). This has the additional advantage of drawing on all the policy information contained in the parties’ authoritative statements of election policy, as specified below. 13 The CMP has coded each quasi-sentence5 of the election programs of significant parties in over 50 countries for the post-war period into one of 56 categories covering the full range of public policy. The overall distribution resulting from this is converted into percentages to control for varying length of the text. The main resulting policy measure is a Left-Right scale which groups 13 of the original categories to the Right and 13 to the Left, on largely a priori grounds. Percentaged references to ‘Left’ topics are summed and subtracted from the summed percentages of ‘Right’ topics. This gives a scale running in theory from -100 (totally Left) to +100 (totally Right). In practice parties rarely move beyond ±50. Essentially the Left-Right scale contrasts support for order and security at home and abroad; traditional morality; and ‘freedom’ on the Right, to support for government planning and intervention; welfare and social security; and peaceful internationalism, on the Left. It thus gives an overall summary of policy stances across the whole of the party platform in each election year.6 So we feel that the analyses below do give a pretty comprehensive picture of policy in the countries concerned. Figures 2 and 3 trace median and plurality voter positions in each of 16 nation’s elections from 1950 through 1995, with Figure 2 displaying the traces for ten PR nations and Figure 3 displaying the traces for the six SMDP nations. Table 3 reports a set of summary statistics, by nation, to help describe the details. [Figure 2 about here] [Figure 3 about here] [Table 3 about here] 5 A quasi-sentence can be either a grammatical sentence or ‘an argument or phrase which is the verbal expression of one idea or meaning. It is often marked off in a text by commas or (semi)colons. Long sentences may contain more than one argument so that they need to be broken up into quasi-sentences’ Klingemann et al (2006) xxiii 6 Incidentally the median elector position we used to identify the electoral median party above, also derives from combining information about party positions on the Left-Right scale with their vote as suggested by Kim & Fording (1998, 2001) and reported in Budge et al (2001, 160-6). We have modified the calculation slightly by assuming that the distribution of votes for parties at each end of the array is symmetrical rather than running right out to the end of the continuum. But this produces a substantive difference in estimates only in the US case. 14 But for France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, the median and plurality positions trace one another reliably enough to record a statistically significant positive relationship. Generally the median voter’s position is more centrist and less volatile than the plurality voter’s. This centrism is reflected in the graphs inasmuch as median voter scores tend to stay closer to zero than the plurality voter scores; the lower volatility is apparent from the smoother traces for the median voter with the exceptions of Denmark and Norway. This centrism and lower volatility are also reflected in the statistical summaries, by the slope values exceeding 1.0; a one-unit movement by the median voter is associated with more than a one-unit movement by the plurality voter. The trace of the Austrian plurality voter shows oversteering relative to the median position in the 1950s and to the early 1960s, and then the two traces mostly move in tandem. Tandem movements are also visible in other PR systems except for Switzerland throughout and except for one or two large deviations during the 1970s or 1980s in Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands. Other than Switzerland, the most remarkable mismatches among PR nations are in Denmark and Norway, where the plurality social democratic parties (the Danish Social Democratic Party, SD, and the Norwegian Labour Party, DN) stood almost persistently to the left of the median voter position. This creates the leftward bias of the plurality voter to the left of the median voter as indicated in Table 3 by the statistically significant negative intercepts. The other noticeable but less remarkable mismatches are the rightward bias in Germany and the leftward bias in the Netherlands. These, unlike Denmark and Norway, are nations where once-in-a-while large deviations tend to go just one way. Finally, in regard to PR nations, the Swiss median and plurality voter positions are consistently out of step. From the 1950s through 1980 the Swiss median voter drifted gradually leftward and the plurality voter, a supporter of the SPS/PSS, stood farther Left. Then from 1983 through 1991, while the median voter positions continued their gradual leftward drift, the Swiss liberals, FDP//PRD, took the plurality spot. All of this happened while three of the four major Swiss parties – Social Democrats, Liberals, and Christians (CVP/PDC) – vied in close competition for the plurality position, each with a vote typically in 15 the 20 and 25% range. Close competition among the major left and right parties in the presence of a centrist alternative (in Switzerland, the CVP/PCD) are circumstances where reading a majority electoral position from the median versus the plurality can be, and as we are reporting for Switzerland sometimes is, likely to be very different. In addition to the consistent mismatch in Switzerland, close competition between Left and Right parties and a centrist alternative also contributes to the occasional mismatches in Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Mismatches aside, though they are potentially a problem, the relationships between the voter positions, other than in Switzerland, are not statistically significantly different from one-to-one among PR nations. In nine out of ten PR nations, slopes are a little higher or a little lower than 1.0, and with fairly large standard errors. Generalizing, the matches through time wander about in a not terribly reliable but general pattern not too much out of line with one another. The generalization holds reasonably well for SMDP nations, too, with the exception of France. The slopes are roughly in the neighborhood of 1.0 - even less reliable than PR nation slopes. In the United States we see persistent oversteering of the plurality relative to median positions and almost as much in the United Kingdom. From the oversteering come relatively large slopes (Table 3, b > 1.4). For Australia and New Zealand, we see loosely consistent tracking of the median positions by the plurality positions. In Canada, especially through 1979, we see mostly consistent tracking. France is a different case. It shows no relationship between the median and plurality positions to speak of. It is similar in this to Switzerland, except that the median voter position does not show such a consistent leftward drift. As in Switzerland, however, a major party on the right (Gaullists and their progeny) was the plurality winner of middling size from the start of the Fifth Republic until 1980, after which the major opposition party, the Socialists, PS, emerged as the middling size plurality winner – (the vote percentages refer to the first ballot). And, just as PS fortunes rose, the median voter moved rightward. In the series of elections 16 of the Fifth Republic, through 1993, all of this produces essentially no relationship between electoral median and plurality positions. Usually the median and plurality voter positions give correlated readings of which direction, Left versus Right, an electorate signals the parliament and government to go. In a few cases – Switzerland and France throughout, along with Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands once in a while – movements of the plurality and median voter positions give very different readings.7 When this is the case, the elections give ambiguous messages about whether it is plausible to consider the median or plurality voter position as carrying the electoral majority preference. The ambiguity arises most seriously when two parties are in close competition for a plurality vote e.g. the German case, where two parties generally receive vote percentages above 40 and a small party (vote <10%) is at the electoral median. Here it is arguable which large party to empower. Thus it is reasonable to think about empowering either or both. An alternative which tempers this choice is to hand over power to the median party or to include the median party in government along with one of the large parties. All of these post-election responses have emerged in Germany, and all are reasonable and ‘democratic’, accommodating both ‘majoritarian’ and ‘proportional’ responses. When the close competitors for the plurality spot receive middling size vote shares, it also makes sense, arguably, to empower the median position, alone or in addition to the plurality position, as in Belgium and the Netherlands. Government participation is one thing but what government decides to do is not wholly determined by this especially under coalitions. Our next step in the analysis asks what government policy positions emerge from the election results. WHAT DIFFERENCE DOES PLURALITY OR MEDIAN ENDORSEMENT MAKE TO GOVERNMENT POLICY? 7 In Switzerland this may not matter too much given that the federal government is formed by a permanent coalition of the four large parties and much policy is delegated to cantons. Frequent referendums and initiatives also supplement the policy messages given by general elections. 17 Democracies tend to privilege the electoral plurality over the median in forming governments. Reading electoral majorities in terms of forming around the median or plurality electoral party shows a loose but consistent relationship between the policy directions they point towards in most countries most of the time. In countries where the loose connection breaks down for a short series of elections (Belgium, Germany, Ireland, and Italy) and in two where the relationship breaks down completely (Switzerland and France, and perhaps three, if we include the Netherlands) governments usually form as coalitions. Coalitions hold the potential of splitting a difference and thereby saving the balance of representation. With that possibility in mind, we put our government and voter findings together and enquire whether government policy positions follow the direction indicated by either the median or plurality voter. Perhaps the strongest empirical generalization in political science is that parliamentary seat proportions among parties in government relate very closely to the proportion of cabinet portfolios held by the parties (Browne and Franklin 1973; see Warwick and Druckman 2006 for a recent review). With Kim and Fording (2002) we rely on this oftrepeated finding to score government policy positions, Left-Right, as seat-weighted policy positions of parties in government. Thus, when two parties are in government, one with 25 seats and scoring 0 on the Left-Right metric and the other with 75 seats and scoring +20 on the Left-Right metric, the government’s position is +15 (i.e., 25*0 + .75*20). And, when a plurality party holds all the cabinet portfolios, as it often does in SMDP systems with singleparty majority governments, the government policy score is equal to that one party’s LeftRight score. Table 4 reports the relationships, by country, between government policy positions, estimated in this way, and the plurality voter’s position. For comparison purposes, to see how well government positions also align through time with median voter positions, Table 5 reports that set of relationships by country.8 So far as Table 4 goes, nine out of ten PR 8 The relationships are weighted by the proportion of time governments held office. A government that holds office for four years receives four times the weight of a government holding 18 country slopes and five out of six SMDP country slopes are less than 1.0, (often statistically significantly lower than 1.0 under PR). This indicates a near uniform tendency for governments’ policy positions to be more centrist than would be the case were governments to follow the plurality voter position on a one-to-one basis. Importantly, because we have seen that the median voter is more centrist than the plurality voter, it also indicates erring on the side of median-based ‘proportionality’ on policy. [Table 4 about here] [Table 5 about here] The results in Table 5 show that six out of ten PR nations display a centrism which is not quite so centrist as to match the median voter positions, however. The relationship is statistically significantly greater than 1.0 in two cases (Italy and Sweden, using a one-tail test). Among SMDP systems, the relationship between government and median voter positions is significantly different from 1.0 only in the United States. And it must be noted that it fails to produce a significant difference for France largely because government positions are so unreliably associated with median voter positions there – indeed so unreliably so that the slope value is not significantly different from zero either! In most countries, government positions loosely but consistently track median voter positions (nearly one-to-one). Finally, we can compare the degree to which governments track plurality or median voter positions more faithfully. The correlations show that all SMDP nations have government positions more consistently fitted to the plurality voter position – even though, as we have seen, they are not much at variance with median voter positions either. The PR comparisons are more mixed. The Irish and Swiss governments do not track their plurality voter positions even to a statistically significant degree, while in both nations there are statistically significant relationships with median voter positions – in Switzerland with b = 1.0. office for just one year. The weights are calculated as the proportion of total time from the first government forming after the first election in the 1950s through the end of 1995. Time in government is taken from Woldendorp, Keman, and Budge (2000). So that the number of cases for each country equals the number of governments that formed during the period in that country, the time proportions have been multiplied by the number of governments. 19 Running in the opposite direction are the results for Norway. There the relationship between government and median voter positions is essentially nonexistent, at least reliably so, while Norwegian government positions are reasonably strongly associated with plurality voter positions. With a few exceptions therefore governments follow the policy tracks set by both the plurality and median voter. Indeed, in several countries it is as if governments split the difference in the long run, somewhat more centrist than the plurality voter position and somewhat more extreme than the median voter position. We suspect, therefore that the theoretical ambiguity over whether electoral majorities are best indicated by the plurality or median voter position is not often going to be of great moment in practical terms. Either or both would lead to the same policy decisions being taken. REVIEW AND CONCLUSIONS This discussion has brought together theoretical concerns about majority representation under democratic rules with comparative evidence, in the tradition of Lijphart’s (1968, 1984, 1999) analyses and particularly Powell’s own (2000) and collaborative (1994, 2001) work. It has hopefully extended and deepened these authors’ concerns by suggesting that ‘two visions’ of how to respond to majority wishes – or even to conceive of a majority – coexist within every democracy rather than distinguishing one type of democracy from another. (Though, as we have just seen, a slight tendency to favour the plurality under SMDP still remains.) Both the ‘proportional’ and ‘majoritarian’ visions are embedded within the very structure of representative general elections, where voters are asked to decide on a number of questions, only some of them bearing directly on policy: which government do they want? which candidate do they prefer? which party do they like best? We cannot therefore assume that voters simply choose the party closest to them on policy, which would lead to the party preferred by the median voter being the obvious carrier of majority preferences (and possibly becoming the plurality party too cf Downs, 1957, 118). On the other hand, we cannot 20 dismiss the possibility that policy voting occurs. But whether in a general election it favours the median or plurality party is obscure. Since elections overwhelmingly fail to produce a spontaneous majority in practice, there is no guarantee that the median based ‘proportional’ and plurality based ‘majoritarian’ positions coincide (though they do in 44% of the cases we examined). Even where they are different however both have claims to represent popular opinion, and neither claim can be convincingly denied in the absence of pure policy-voting. The horns of this dilemma are nonetheless blunted for most democracies by the fact that, under a stable party system, both median and plurality shift marginally from election to election in the same policy direction. Their actual policy positions may diverge but they generally give the same indications of what the popular majority wants in the way of change. In this sense governments – regardless of whether plurality or median parties form them – can claim popular support for their policy innovations, conforming as they do to both ‘proportional’ and ‘majoritarian’ messages from the election. In terms of government participation its clear identifiability (Powell, 2000, 61-80) gives the plurality party an advantage, even under proportional rules and coalition-formation. Balancing this, government policy for the most part seems to cater both for median and plurality positions even under single-party governments. This is not surprising, given the similarities we have identified between the policy messages they provide. Superficially, our finding that election-messages tend to point in the same direction resembles Soroka & Wlezien’s (2008) conclusion that there is little difference between the preferences of various ‘sub-constituencies’ in the United States (rich and poor, voters and non-voters, with some exceptions in regard to specific policy areas and perhaps levels of education). This is in contrast to the findings of Gilens (2009) that there are wide variations between different groups, a view supported by the comparative findings of Adams & Ezrow (2009) on European opinion leaders. These are both left-leaning and disproportionately influential in parties and on governments. 21 It would be nice if our findings contributed to this important debate. However we have to point out that they are quite tangentle to the questions at issue in it. The positions identified by election results could be those favoured by any demographic group and there is nothing to say whether plurality or median policy positions favour Right or Left, rich or poor. Indeed it is quite likely that over time the balance of opinion, as indicated by the election results, shifts between all of these groups. Our findings therefore relate more to the functioning of the central democratic institution of elections than to their substantive impact. Whichever way one looks at them, from a median or plurality point of view, elections tend to relay the same message about majority preferences. Why should this be so? We have already pointed out that the similarity between the median and plurality preference is neither necessary nor logical in nature. It depends on the broad overall stability of the party system at the electoral level. Where sequential elections simply transfer votes between existing parties, even though the transfers may be relatively large, we can expect that a plurality shift between Left and Right parties for example will be accompanied by a shift in the median – probably between Centre-Left and Centre-Right. This is because the median position, being estimated from the distribution of voters over the party alternatives, will also register the movement of support from Left to Right. Party systems in established democracies such as the ones examined here are reasonably stable most of the time. Hence only limited transfers of votes occur between election and election, median and plurality move in the same policy direction, and so governments can be responsive to both. Where however a challenger suddenly takes support from an established party on either Right or Left, splitting that ideological grouping, the plurality position may be taken by an unchallenged party on the other wing. The median however will still reflect the balance of votes between the ideological groupings rather than between the parties as such. If the new challenger and the targeted party between them have increased or retained their overall support the median will stay stable or shift towards them. In that case the messages governments take from the election results will differ. This 22 simply reflects the general political upheaval that is taking place in that election however, signalled by divisions in established parties or by new entrants to the electoral arena. When the election situation stabilizes the median and plurality will again send the same message to governments about the policy direction to take. What our evidence reveals therefore, for the 16 post-war democracies we have examined, is that elections organized by parties generally provide loose but consistent representation of electoral preferences whether these are aggregated in ‘proportional’ or ‘majoritarian’ terms. This holds true whether, operationally, the majority is taken to be represented by either the median or plurality voter positions, thus resolving the problems of choice which open up in theory between the two. The two ‘visions’ of democracy, rather than competing or distinguishing one type of democracy sharply from another, in practice generally complement each other within the established framework of most democratic systems. 23 Table 1 Arguments for the median or plurality positions to be taken as representing the majority position under mixed motive voting Arguments for the median position as representing the majority preference:- Arguments for the plurality position as representing the majority preference:- 1. The median voter is essential to creating a majority under the declared distribution of votes so her position is the only one common to all majorities and can be taken as the one they would arrive at by negotiation and discussion 1. The plurality grouping only failed to become the majority by accident, possibly owing to non-policy based factors affecting voting 2. The median position is defined by the voting preferences of all electors, not an extreme group as could be the case with the plurality 2. The plurality emerges spontaneously as a result of voting. It is not artificially calculated from the final distribution of votes and is thus readily identified and held accountable 3. The median minimizes the overall distance between individual declared preferences and the majority position endorsed by the election. 3. The plurality position is the single revealed preference most representative of majority opinion, particularly if it clearly has more support than the next largest party grouping 4. There is always a plurality party1 but it is not always easy to identify the ‘true’ and ‘unique’ policy median 1 Of course two parties might be returned with the same plurality. In this case both have to be regarded as having its attributes. 24 25 26 27 28 FIGURE 1 The Median Position E and Plurality Position G in a One-dimensional Policy Space Parties A B C D E F G Left % Seats/Votes Right 10% 20% 7% 6% 10% 6% 41% 29 30 31 REFERENCES Adams, James, Michael Clark, Lawrence Ezrow, and Garrett Glasgow. 2004. “Understanding Change and Stability in Party Ideologies: Do Parties Respond to Public Opinion or Past Election Results?” British Journal of Political Science 34: 589610. Adams, James and Lawrence Ezrow. 2009. Who Do European Parties Represent? How Western European Parties Represent the Policy Preferences of Opinion Leaders. Journal of Politics 71, 206-223. Axelrod, Robert. 1970. Conflict of Interest. Chicago, Markham. Black, Duncan. 1958. The Theory of Committees and Elections, (Cambridge, CUP) Black, Duncan. 1948. “On the Rationale of Group Decision Making.” Journal of Political Economy 56: 23-34 Blais, André and Marc André Bodet. 2006. “Does Proportional Representation Foster Closer Congruence between Citizens and Policymakers?” Comparative Political Studies 39: 1243-62. Browne, Eric and Mark Franklin. 1973. Aspects of Coalition Payoffs in European Parliamentary Democracies. American Political Science Review 67: 453-69. Budge, Ian, Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Eric Tannenbaum, et al. 2001. Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Voters and Governments 1945-1998. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Campbell, Angus, Philip Converse, Warren Miller, Donald E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York, Wiley. Downs,Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York, NY: Harper and Row. Erikson, Robert S., Michael B. MacKuen, and James A. Stimson. 2002. The Macro Polity. Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Ezrow, Lawrence. 2005. Are Moderate Parties Rewarded in Multi-Party Systems? A Pooled Analysis of Western European Elections1984-1998. European Journal of Political Research, 44, 881-898. Gilens, Martin. 2009. “Preference Gaps and Inequality in Representations.” PS, 319-327. Golder, Matt and Jacek Strmski. 2007. “Ideological Congruence and Two Visions of Democracy.” Unpublished manuscript, Florida State University (July 23 version). Huber, John D. and Ronald Inglehart. 1995. “Expert Interpretations of Party Space and Party Locations in 42 Societies.” Party Politics 1: 73-111. Huber, John D. and G. Bingham Powell. 1994. “Congruence between Citizens and Policymakers in Two Visions of Liberal Democracy.” World Politics 46: 291-326. Kim, HeeMin and Richard Fording. 1998. “Voter Ideology in Western Democracies, 19461989.” European Journal of Political Research 33: 73-97. Kim, HeeMin and Richard Fording. 2002. Government Partisanship in Western Democracies, 1945-1998. European Journal of Political Research 41:187-206. 32 Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Ian Budge, and Michael D. McDonald. 2006. Mapping Policy Preferences II: Estimates for Parties, Voters and Governments in Eastern Europe, European Union and OECD 1990-2003. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lijphart, Arend. 1968. The Politics of Accommodation. New Haven, CT: Yale. Lijphart, Arend. 1977. Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Lijphart, Arend. 1984. Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Lijphart, Arend. 1994. Electoral Systems and Party Systems: A Study of Twenty-Seven Democracies, 1945-1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lijphart, Arend. 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven. CT: Yale University Press. McDonald, Michael D., Silvia M. Mendes, and Ian Budge. 2004. “What Are Elections For? Conferring the Median Mandate.” British Journal of Political Science. 34: 1-26. McDonald, Michael D. and Ian Budge. 2005. Elections, Parties, Democracy: Conferring the Median Mandate. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. May, John D. 1978. ‘Defining Democracy: A Bid for Coherence & Consensus’. Political Studies 26: 1-14. Müller, Wolfgang C. and Kaare Strom. 2000. Coalition Government in Western Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Powell, G. Bingham, Jr. 1982. Contemporary Democracies: Participation, Stability, and Violence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Powell, G. Bingham, Jr. 2000. Elections as Instrument of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Powell, G. Bingham and Georg Vanberg. 2000. “Election Laws, Disproportionality, and Median Correspondence: Implications for Two Visions of Democracy.” British Journal of Political Science 30: 383-411. Saward, Michael. 1998. The Terms of Democracy. Cambridge: Polity. Schattschneider, E.E. 1942. Party Government. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Schattschneider, E.E. 1960. Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist;s View of Democracy in America. New York, NY: Holt,Rinehart and Winston. Soroka, Stuart and Christopher Wlezien. 2004. Opinion representation and policy feedback: Canada in Comparative Perspective. Canadian Journal of Political Science 37: 53160. Soroka, Stuart and Christopher Wlezien. 2005. Opinion-Policy Dynamics: Public Preferences and Public Expenditure in the UK. British Journal of Political Science 35: 665-89. Soroka, Stuart and Christopher Wlezien. 2008. ‘On the Limits to Inequality in Representation’. PS 319-327. 33 Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1950 [1942]. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. 3rd ed. New York: Harper & Brothers. Volkens, Andrea, Kai-Uwe Schnapp and Jürgen Lass. 1992. Data Handbook on Election Results and Seats in the National Parliaments of 26 Contemporary Democracies, 1945-1990. Berlin: WZB. Warwick, Paul V. and James N. Druckman. 2001. Portfolio Salience and the Proportionality of Payoffs in Coalition Governments. British Journal of Political Science 398: 627649. Warwick, Paul and James N. Druckman. 2006. The Portfolio Allocation Paradox: An Investigation into the Nature of a Very Strong but Puzzling Relationship. European Journal of Political Research 45: 635-665. Wlezien, Christopher. 1996. Dynamics of Representation: The Case of US Spending on Defense. British Journal of Political Science 26: 81-103. Wlezien,Christopher and Stuart N. Soroka. 2009. ‘The Relationship between Public Opinion and Policy’, Chap. 43 of Dalton, Russell and H-D Klingemann. Oxford Handbook of Political Behaviour. Oxford, OUP. Woldendorp, Jaap, Hans Keman and Ian Budge. 2000. Party Government in 48 Democracies (1945-1998). Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic.