0142159X.2012.660213

advertisement

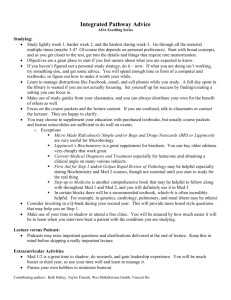

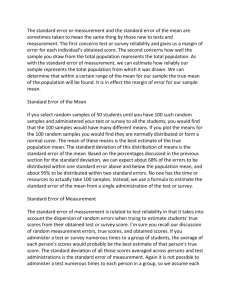

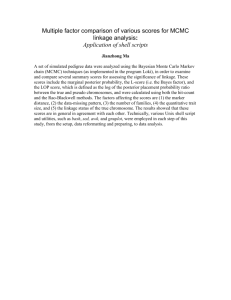

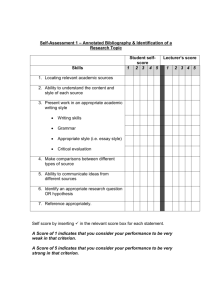

2012; 34: e242–e250 WEB PAPER Using an objective structured video exam to identify differential understanding of aspects of communication skills DANIELLE A. BARIBEAU1, ILYA MUKOVOZOV1, THOMAS SABLJIC2, KEVIN W. EVA3 & CARL B. DELOTTINVILLE2 1 University of Toronto, Canada, 2McMaster University, Canada, 3University of British Columbia, Canada Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. Abstract Background: Effective communication in health care is associated with patient satisfaction and improved clinical outcomes. Professional schools increasingly incorporate communication training into their curricula. The objective structured video exam (OSVE) is a video-based examination that provides an economical way of assessing students’ knowledge of communication skills. This study presents a scoring strategy that enables blueprinting of an OSVE to consensus guidelines, to determine which aspects of communication skills create the most difficulty for students to understand and to what degree understanding improves through experiential communication skills training. Methods: Five interactions between a healthcare professional and client were scripted and filmed using standardized patients. The dialogues were mapped onto the Kalamazoo consensus statement by having five communication experts view each video and identify effective and ineffective use of communication skills. Undergraduate students enrolled in a communications course completed an OSVE on three occasions. Results: A total of 79 students completed at least one testing session. The scores assigned supported the validity of the scoring strategy as an indication of knowledge growth. Considerable variability was observed across Kalamazoo sub-domains. Conclusion: With further refining, this scoring approach may prove useful for educators to tailor their education and assessment practices to specific consensus guidelines. Introduction Practice points Training in communication skills has been shown to improve clinical competence and interviewing skills in a variety of health care disciplines (Aspregen 1999; Yedidia et al. 2003; Haak et al. 2008). That being said, the intangible nature of communication skills creates a challenge for curriculum development and competence assessment. Evaluations of student communication skills during Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) have shown that communication skills vary on a case-by-case basis thus necessitating that a series of observations be collected (Kroboth et al. 1992; Hodges et al. 1996; Boulet et al. 1998; Guiton et al. 2004). Repeated evaluations using the OSCE format place a high demand on financial resources. An offshoot of the OSCE, the objective structured video exam (OSVE), is a video-based written examination that provides an efficient and economical way of assessing a student’s knowledge of communication skills in a classroom setting (Humphris & Kaney 2000). With this technique, students are typically asked to watch a series of interactions on video between a doctor and a patient. The videos are followed by written questions, designed to assess the students’ ability to identify, understand, or critique the communication . Knowledge of communication skills increases through an experiential approach to learning. . The OSVE is a cost effective way of measuring relative strengths and weaknesses in knowledge of communication skills. . Training for novices should focus on the development of patient-centered communication skills and on how to recognize and improve ineffective communication. skills portrayed in the video. Evaluation forms have taken on a variety of formats, including multiple choice and short answer questioning (Hulsman et al. 2006; Simpson et al. 2006). A variety of programs have incorporated an OSVE into their curricula (e.g., Simpson et al. 2006), but the validity of the tool as an assessment instrument has not been studied extensively (Humphris & Kaney 2000, 2001; Humphris 2002; Hulsman et al. 2006). With respect to curriculum development, the literature supports an experiential approach to communication skills training, in which students learn by interacting with real or standardized patients (SPs), while receiving feedback from Correspondence: C. B. deLottinville, Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours) Program, MDCL-3316, Faculty of Medicine, McMaster University, 1200 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8N 3Z5, Canada. Email: carl.delottinville@learnlink.mcmaster.ca Danielle A. Baribeau, Ilya Mukovozov and Thomas Sabljic contributed equally to this article e242 ISSN 0142–159X print/ISSN 1466–187X online/12/040242–9 ß 2012 Informa UK Ltd. DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.660213 Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. Objective structured video exam Figure 1. Kalamazoo consensus statement tasks (bold face) and skills adapted for the undergraduate level with assigned coding number for use in OSVE scoring. instructors (Knowles et al. 2001; Shaw 2006; Von Fragstein et al. 2008). Curriculum development can now be guided by expert consensus and written guidelines that describe specific communication skills. For example, in 1999, leaders in the field of medical education agreed upon a set of essential communication skills and tasks, entitled The Kalamazoo consensus statement, which has since served as a framework for communication skills training (Makoul 2001). In short, the framework highlights the following seven essential elements or tasks as being fundamental to clinical communication: (1) building a relationship, (2) opening the discussion, (3) gathering information, (4) understanding the patient’s perspective, (5) sharing information, (6) reaching agreement on problems and plans, and (7) providing closure. Specific skill sets are identified for each of the above tasks (Figure 1; Makoul 2001). The skills described under 1, 2, 4, and 6 focus on enhancing the subjective patient experience, and relate more to the interpersonal interaction, which we have termed ‘‘patientcentered tasks.’’ Skills 3, 5, and 7 outline organizational tasks necessary to structure a medical encounter and acquire or give information, which we have terms ‘‘information or organization tasks.’’ There is considerable evidence that both categories are essential for doctor–patient communication (Barry et al. 2000; Ward et al. 2003; Windish et al. 2005; Ruiz-Moral et al. 2006). Little et al. (2001), for example, showed that when surveyed, patients equally valued both patient-centered tasks (e.g. being listened to, having their concerns understood, establishing a relationship, reaching agreement on plans) as well as information or organization tasks (e.g. providing information, clear explanations, suggestions for illness prevention). With respect to education and training, the literature suggests that medical students and physicians alike tend to excel at organization or information-based tasks, but struggle with patient-centered tasks. Many studies have quantified the high frequency with which physicians miss opportunities to provide emotional support or empathy during clinical encounters (Levinson et al. 2000; Morse et al. 2008). Aspegren and Lonberg-Madsen (2005) showed that medical students and seasoned physicians alike were experts in content or information-based skills but lacked process and perceptual skills related to building rapport and developing the doctor–patient relationship. Communication skills training has repeatedly been shown to enhance patient-centered communication. For example, Perera et al. (2009) showed that medical students who received additional feedback on their communication improved significantly in understanding the patient and building the relationship. No improvement was noted with respect to information/organization tasks like sharing information and closing the discussion. Back et al. (2011), found that prior to communication skills training, oncology fellows missed opportunities to respond to emotional cues, but this was improved with an experiential workshop. Bylund et al. (2010) showed that at baseline, physicians frequently used e243 Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. D. A. Baribeau et al. organization skills, but were relatively weaker at patientcentered skills like negotiating an agenda, checking for understanding or sharing in decision making. With training, significant improvements were made in two patient-centered tasks: negotiating the agenda and understanding the patient’s perspective. Similarly, Butow et al. (2008), showed that frequency of skill use was variable at baseline, but that training increased the physicians’ ability to reach agreement in decision making and elicit patient emotions. It is unknown whether this pattern, in which the organizational aspects of communication are performed better than patient-centered aspects, represents a basic communication tendency, or alternatively whether it is the result of knowledge gained through professional training. Furthermore, it is unknown whether one first requires a knowledge base on the structure of clinical interviewing in order to capitalize on training focused on patient-centered communication. Determining whether or not the same patterns as described in the preceding paragraphs exist in a pre-clinical sample of students would help address both of these issues, thereby yielding further insight into the appropriate timing and strategies for communication skills training at varying levels of experience. In this study, we use a quasi-experimental, pre-test–posttest design to test which specific communication elements described in the Kalamzoo consensus pose the greatest difficulty to pre-clinical non-professional undergraduate students, and to what extent knowledge of these skills may be differentially learned in an introductory communication skills course. We demonstrate a way to map an OSVE scoring key onto current consensus guidelines and then present multiple videotaped scenarios to students that represented a variety of professional contexts. We use a response form that requires students to identify effective and ineffective aspects of the skills demonstrated in the videos. To guard against the possibility that any increase in scores could be attributed to general maturation or learning derived from the pre-test, a pair of pre-tests was used for a portion of the sample. Retention of knowledge was assessed with a 4-month follow-up test for the other half of the sample. Extrapolating from the literature, we hypothesize that students will be overall more effective at recognizing information or organization tasks. With training, we anticipate that patient-centered task recognition should improve, particularly with respect to understanding the patient’s perspective and reaching agreement. Methods Part A: Design of the OSVE Design of video vignettes. Five interactions between a health care professional and client were scripted to contain 5 min of dialogue. Each of these scenarios was written deliberately to contain many elements of effective and ineffective communication skills based on the Kalamazoo consensus statement. The videos were intended to be realistic, and were not focused on a particular subset of skills. SPs were recruited from the Standardized Patient Program at the Centre for SimulationBased Learning at the McMaster University Medical Centre. e244 A total of five videos were filmed using SPs, and each was cropped to a duration lasting from 4 to 5.5 min in length. OSVE response forms. The dialogue in each video was transcribed verbatim into a response form, adjacent to two blank columns (Figure 2). Participants were instructed to identify and evaluate the interviewer’s communication skills by commenting in the blank columns adjacent to the area in the script where they perceived communication skills to be employed. The responses were requested in ‘‘free text’’ form, in that the comments were not restricted to any particular aspect of the dialogue. Participants recorded comments on effective communication skills in column A, whereas comments on ineffective communication skills or missed opportunities to use communication skills were recorded in column B. Part B: Development of a criterion standard Acquiring expert responses. It was important to determine which communication skills were portrayed by the SPs in the videos in an identifiable form and, therefore, could be evaluated on the scoring key (criterion standard). To this end, rather than relying solely on the scenario author’s opinion or intention, five communication skills experts were recruited to create a criterion standard. Each expert had at least 15 years of experience teaching communication skills and was very familiar with the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Experts followed a testing regimen identical to that which would subsequently be applied to the student participants (i.e., an initial viewing of a video scenario followed by 9 min to complete the response form and a second viewing). In one testing session, the experts were instructed to identify and comment on communication skills portrayed in all five video scenarios. Interpreting expert responses. The Kalamazoo consensus statement was used as a template for interpreting expert responses. Numeric codes were assigned to the seven communication categories or (where possible) to each of the 24 more specific communication skills that reside within specific categories for a total of 31 possible codes (Figure 1). Carl Delottinville, Ilya Mukovozov, Thomas Sabljic, and Danielle Baribeau then independently matched the expert responses to the most appropriate items on the template. Each author applied the template codes to expert responses for all five video scenarios and for all five experts. Agreement between authors with respect to the coding scheme was then assessed. Using binomial probability theorem, it was determined that the probability of at least three out of four authors agreeing on one of 31 possible codes by chance alone was 0.01%. Using this strict criterion for consensus resulted in the inclusion of only expert responses that could be clearly attributed to one communication category or skill. Comparing responses between experts. The responses that were similarly coded by at least three authors were then compared across experts for each line of the dialogue. Where two or more of the five experts identified the same specific task or communication category in the same line range, the line Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. Objective structured video exam Figure 2. Sample OSVE response form. The students are instructed to describe the communication skills or tasks that were effective (column A) or inneffective (column B), adjacent to the line number where these skills occur in the dialog. range was marked and the response was retained as a component of the criterion standard. This relatively liberal criterion was adopted because, with roughly 100 lines of text per case on average (range 80–182), two response columns and 32 possible codes (the 31 codes in Figure 1 plus the chance that a line of text would not be coded) the likelihood that at least two experts would select the same line of dialogue and assign the same code to that dialogue by chance alone is only 0.03%. Figure 3 illustrates a sample portion of the criterion standard for a single video. The criterion standard. The protocol described in section B generated five OSVE marking keys each containing between 26 and 36 scorable responses distributed between both columns. Some skills were represented more frequently than others. Table 1 demonstrates the number of times each skill was portrayed in each video scenario and in which column the skills were identified as per the criterion standard. Part C: Student population and testing Figure 3. Sample OSVE marking scheme. The communciation skills or tasks and their line ranges, identified by a panel of experts, are indicated on the marking scheme. The bracketed number corresponds to the order of the responses and the subsequent double-digit number indicates the code that corresponds with the specific behaviors presented in Figure 1. The student population. We recruited from a population of 87 non-professional undergraduate students enrolled in a third year Communication Skills course for the 2007/2008 academic year. Ethics approval was granted by McMaster University’s Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Board. On agreeing to participate in the study, students were randomly allocated an anonymous participant number, thus blinding the authors to the participant’s identity, semester of enrollment, and test administration protocol. e245 D. A. Baribeau et al. Table 1. Frequency, type (according to Kalamazoo consensus) and quality of communication skill (A: effective vs. B: ineffective/missed) listed in the criterion scoring sheet. Column Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. 10. Builds and sustains a trusting relationship 20. Opens the discussion 30. Gathers information 40. Understands the interviewee’s perspective 50. Shares information 60. Reaches agreement 70. Provides closure Total Video A Video B Video C Video D Video E A B A B A B A B A B 10 1 3 7 2 3 2 28 3 2 1 1 0 0 1 8 5 1 1 1 2 0 0 10 6 0 0 5 2 3 1 17 4 1 7 4 0 1 0 17 4 0 0 6 0 0 1 11 7 1 1 2 1 1 0 13 4 0 0 4 0 3 2 13 5 0 2 2 5 0 0 14 6 0 1 4 0 2 1 14 Total 54 6 16 36 12 13 8 145 Figure 4. Study design. A cross-over study design permitted simultaneous testing for communication skills knowledge acquisition, knowledge retention, as well as learning effects from repeated testing. The communication skills course. The communication skills course, as the educational intervention, consisted of 3 class hours per week for 12 weeks. This course used an experiential approach to communication skills training with SP interactions lasting 2 h each week accompanied by immediate tutor and group feedback. Students were also given an opportunity to observe and reflect on their own interviews, which were video recorded. The students completed weekly journal reflections on their communication skills as well as two written projects incorporating evidence-based literature specific to communication skills. Testing protocol. Half of the students (n ¼ 45) were enrolled in the semester 1 course (September to December), while the other half (n ¼ 42) were enrolled in semester 2 (January to April). Students in both semesters were requested to attend three separate testing sessions, the first in September, the second in December/January, and the third in April. Mean scores were compared before and after the educational intervention, to measure the effect of communication skills training and to control for inter-student variability. Additionally, semester 1 students were tested 4 months after completing the course, to measure knowledge retention. Semester 2 students were tested 4 months prior to, and directly prior to the educational intervention, to measure the learning effect derived from repeated OSVE participation. As such, each semester of students was requested to attend one testing session outside of allotted classroom time. See Figure 4 for an illustration of the research design. e246 Testing sessions. The sequence of video administration was planned such that each student viewed three video scenarios during each of the three testing sessions. During the second and third testing sessions, they viewed two previously viewed scenarios and one new scenario. The order of video administration varied by testing session, such that each student viewed each video no more than twice, and each video was represented across all testing sessions. As previously described above, the students were tasked to identify and comment on the effective use of communication skills portrayed by the interviewer in column A, as well as areas of ineffective use of communication skills or missed opportunities for communication skills in column B. A pilot testing session was conducted with a sample group of student volunteers (n ¼ 4). From this, it was determined that 9 min spaced between two video viewings provided adequate time for students to complete the OSVE response form for each video vignette. Viewing three different videos and completing three response forms in this way required a total testing time of approximately 1 h. Marking student response forms. Danielle Baribeau, Thomas Sabljic, and Ilya Mukovozov subsequently compared student responses to those on the criterion standard developed from expert responses. Where a student provided the same response as an expert in the same column and line range, one mark was allocated. Marks were not removed for incorrect responses. During the marking of student responses, specific communication skills were interpreted as dependent on the Objective structured video exam communication categories. Where a communication category was considered a correct response on the criterion standard, a student could receive a mark for commenting on a specific skill within that category. This decision was made to avoid being overly narrow in interpreting student-expert alignment, and was consistently applied to all testing sessions. Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. Part D: Analysis Student responses were analyzed with respect to the percent correct (i.e., the number of correct items noted by participants/ the number included in the answer key generated by the expert panel), as well as the percent accuracy (number of correct items noted by the participants/total number of responses noted by participants). Percentage scores were used as opposed to absolute scores given that each video scenario contained a variable number of potentially correct items under the different skill sub-domains. This avoided skewing the relative contribution of student scores toward OSVE vignettes with more items. It also enabled a ready comparison across communication skill category sub-domains. The percent correct score for each sub-domain was averaged across all five videos. Mixed design analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on this variable, treating term in which participants received the educational intervention (Fall vs Winter) as a between subjects factor and test administration (September, January, or April) as a repeated measure. Planned comparison t-tests were used to determine the source of any significant effects. ANOVA was similarly used to determine which specific aspects of communication skills students had the greatest difficulty identifying. Results In total, 79 students (90.1% of all eligible participants) contributed data to this study although the sample size varied across administration (n ¼ 61, 69, and 39 for tests 1, 2, and 3, respectively). A total of 27/79 students attended all three testing sessions. Mean scores for students who completed all three sessions were compared to those who completed only one or two testing sessions. Pre-intervention scores were slightly higher for students who attended all three testing sessions with respect to percent correct (18.6% vs 15.3%, p ¼ 0.02), but were not significantly different with respect to percent accuracy (39.1% vs 37.5%, p ¼ 0.56) or with respect to either measure post-intervention ( percent accuracy 51.3 vs 54.6, p ¼ 0.27, percent correct ¼ 28.5 vs 31.2, p ¼ 0.08). Authors had a high level of agreement with respect to scoring the student responses. The inter-rater reliability calculations with respect to scoring agreement for each video scenario were: Scenarios A ¼ 0.95; B ¼ 0.95; C ¼ 0.90; D ¼ 0.92; and E ¼ 0.95. Both percent accuracy and percent correct scores increased following the communication skills training. The total number of responses provided by each student also increased. Overall mean percent correct scores by term and testing session are illustrated in Figure 5. For percent accuracy, Term 1 mean scores increased from 39.2% to 51.3% after the intervention. Term 2 percent accuracy mean scores increased from 36.4% Figure 5. Student scores on the OSVE. T1 (Term 1): Results shown before and after taking a communication skills course, as well as when tested for retention after 4 months. T2 (Term 2): Results shown from repeated pre-intervention testing, as well as before and after taking a communication skills course. to 55.8%. The total number of given responses increased from a mean of 12.7 (T1) and 12.9 (T2) to 17.2 (T1) and 15.2 (T2). A mixed design ANOVA performed on the percent correct scores revealed no main effect of semester (F 5 1, p 4 0.4), a significant effect of session (F ¼ 11.1, p 5 0.001) and a semester session interaction that bordered on significance (F ¼ 2.8, p 5 0.08). Planned post hoc comparisons revealed significant differences in the places that would be expected given the above description: In semester 1 students, pre-test scores were significantly lower than post-test scores (t ¼ 5.6, p 5 0.001) and post-test scores did not differ from retention scores (t ¼ 0.9, p 4 0.3). In semester 2 students, both pre-test scores were significantly lower than post-test scores (t ¼ 4.6 and 5.8, p 5 0.001). To flesh out which aspects of communication skills gave students the greatest difficulty, sub-scores were created for both the ‘‘effectively used’’ items from the answer key and the ‘‘missed opportunity/ineffective’’ items as well as for each of the sub-domains included in the Kalamazoo consensus statement (Figure 1). ANOVA revealed that students were significantly better at correctly identifying aspects of communication skills that were effectively used by individuals in the OSVE videos (mean ¼ 24.2% correct, 95% CI ¼ 22.3–26.1%) relative to identifying missed opportunities or ineffective communication (mean ¼ 18.6% correct, 95% CI ¼ 17.0–20.1%; F ¼ 31.8, p 5 0.001). The correlation between percent correct on ‘‘effectively used’’ items and ‘‘missed opportunity/ineffective’’ items was r ¼ 0.36, p 5 0.01. With respect to the Kalamazoo sub-domains, ANOVA similarly revealed that statistically meaningful differences exist regarding students’ capacity to identify different aspects of communication skills. A main effect of sub-domain was observed (F ¼ 17.5, p 5 0.001) with mean percent correct ranging from a low of 9.6% (95% CI ¼ 7.9–11.3%) for the ‘‘Reaches Agreement’’ sub-domain and a high of 29.6% (95% CI ¼ 25.4–33.9%) for the ‘‘Shares Information’’ sub-domain. Table 2 illustrates the mean percent correct for each of the Kalamazoo consensus statement sub-domains along with a break-down of these scores pre- vs post-test indicating the extent to which students’ knowledge in each sub-domain increased as a result of the learning enabled by the educational intervention. In four of the seven domains, statistically e247 D. A. Baribeau et al. Table 2. Percent correct as a function of Kalamazoo consensus statement sub-scores. Skill sub-type 10. 20. 30. 40. 50. 60. 70. Builds and sustains a trusting relationship Opens the discussion Gathers information Understands the interviewee’s perspective Shares information Reaches agreement Provides closure Mean percent correct across all testing session and all videos (95% confidence interval) 17.7% 20.6% 23.4% 23.7% 29.6% 9.6% 27.6% (16.0–19.5) (16.5–24.8) (19.6–27.4) (21.5–25.9) (25.4–33.9) (7.9–11.4) (23.0–32.2) Pre-test mean percent correct Post-test mean percent correct p-Value comparing pre-test to post-test 21.4 24.0 14.1 16.9 26.0 5.8 24.0 22.1 16.0 36.3 33.0 30.1 18.2 40.0 0.75 0.24 50.01 50.001 0.55 50.001 50.05 Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. Notes: The overall mean percent correct is based on total set of data collected whereas the pre-test and post-test means are calculated based on only those individuals who contributed data before and after the educational intervention. significant gains in performance were achieved: ‘‘Gathers Information,’’ ‘‘Understands the Interviewee’s Perspective,’’ ‘‘Reaches Agreement,’’ and ‘‘Provides Closure.’’ Cronbach’s alpha examining the consistency with which sub-domain scores differentiate between candidates was found to be 0.54. Discussion In this study, we designed and tested a novel OSVE response form and marking protocol, based on consensus guidelines, to assess knowledge of communication skills. The ‘‘free text’’ design of the response form encouraged students to identify, qualify, and comment on the communication skills they perceived in each video scenario. This approach varies from that which has been reported in other OSVE testing protocols, and represents a method of accommodating the subjective nature of clinical interactions. The development of the criterion standard using expert consensus revealed that experts were more likely to identify communication skills related to the patient experience of the interpersonal interaction (i.e., building the relationship and understanding the patient’s perspective; Table 1). The preprofessional students included in this sample, in contrast, were more likely to identify aspects of communication skills that corresponded with organizational tasks (i.e., sharing information and providing closure; Table 2). This is in line with what has been reported in the literature, that health care students and professionals who receive additional training are more likely to employ patient-centered communication skills. That said, training of these relative novices via an experiential communication skills course led to improvement in four out of seven sub-domains, including patient-centered tasks and concrete/organizational tasks. Previous studies have shown improvement primarily in the patient-centered subdomains. We hypothesize that this difference may relate to the nature of the non-professional undergraduate student population, whom had no prior exposure to either the structure or the skills required for clinical interviewing. As a result, training permitted not only development of patient-centered skills, but also a basic introduction to the structure and format of a clinical encounter. Students were relatively better at identifying communication skills that were correctly demonstrated in a video, and e248 relatively weaker at identifying missed opportunities or generating ideas on how the communication skills demonstrated could be improved. These results, in combination, suggest that pre-clinical training in communication should focus on the patient-centered communication skills, such as relationship building, understanding the patient’s perspective and reaching agreement. Training should be specifically aimed at helping students to identify common mistakes and develop ways to improve the interaction. It is important to note that the communication skills course was not built around the consensus guidelines or the OSVE scenarios used. Students acquired their knowledge through experiential learning, journal reflections, using simulated patients, peer feedback, and by exploring the literature. As such, we consider the results to be reasonably representative of what can be expected of the broader population of pre-clinical students rather than being the specific result of this particular communication skills course. We specify ‘‘pre-clinical’’ because while a high proportion of students in the Bachelor of Health Sciences Program at McMaster University enter medical school upon graduation, this specific course involved a non-professional undergraduate population meaning that the students did not have clinical knowledge to incorporate into their communication skills training. Unfortunately, student participation rates for testing sessions held outside of class time were relatively low, creating a potential selection bias toward more dedicated or interested students. That being said, mean scores for students who completed all three sessions were for the most part not significantly different from those who completed only one or two testing sessions. Further, our data suggest that repeated OSVE administration or maturation throughout the academic year did not in itself improve student knowledge as a pair of pre-tests revealed similar performance as did the post-test vs retention comparison. Further work is required to determine whether or not this OSVE scoring technique could be used to enable tailoring of feedback to individual students or to identify those in need of remediation. Of note, the students achieved relatively low mean percent correct scores, both before and after the study intervention. The low scores may be attributable to the protocol used to generate the criterion standard. Five experts contributed to the Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. Objective structured video exam marking key, but consensus was only required between two experts on a particular item for it to be included in the criterion standard. As a result, each individual expert contributed only 20% of the criterion standard, approximating the percent correct scores achieved by students. A more stringent protocol regarding expert consensus would be expected to raise the mean percent correct by limiting the answer key to those items that are more absolutely observable. This was not done in the context of this study as the relative accuracy across sub-domain was of dominant interest. For those looking to reproduce this type of evaluation for educational purposes, an open discussion among educators during the generation of the marking scheme would be more straightforward and likely appropriate for nonresearch-based endeavors. A final limitation of the study arises from lack of clarity regarding the significance of communication skills knowledge. There is limited data available to enable confident claims that greater knowledge of communication portrayed on OSVEs is associated with performance (Humphris 2002). More research is needed to determine if training and assessment of communication skills knowledge translates to performance in clinical encounters. Conclusions An OSVE based on consensus guidelines with respect to clinical communication was capable of tracking increases in student knowledge of communication skills following an educational intervention. The students’ ability to identify communication skills varied depending on the skill sub-type. Students were better at identifying information or organizationbased tasks such as sharing information and closing the discussion. They were weaker at recognizing patient-centered tasks such as building the relationship and reaching agreement with the patient. Communication skills training resulted in improved recognition of some but not all types of communication skills. Educators in the field of clinical communication may find it useful to evaluate knowledge acquisition of specific communication skill sub-types using OSVEs to enable tailoring of feedback and further curriculum development to the specific deficiencies observed. Pre-clinical training in communication should focus on recognizing opportunities to improve communication skills that enhance the subjective patient experience. Acknowledgments The authors thank Jennifer Gallé, Osama Khan, and Jayant Ramakrishna for their preliminary work on this project. Gratitude is extended to the Bachelor of Health Sciences Program at McMaster University for providing funding and technical support. This research was conducted at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Declaration of interest: The authors report no declarations of interest. Notes on contributors DANIELLE A. BARIBEAU, BHSc, is a medical student at the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. She completed a Bachelor’s degree in Health Sciences in 2008 at McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. ILYA MUKOVOZOV, MSc, is a student in the MD/PhD Program at the University of Toronto, enrolled in the Institute of Medical Science and working as a research associate in the Department of Cell Biology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. THOMAS SABLJIC, MSc, is a doctoral student in the Medical Sciences Program at McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. He completed a Bachelor’s degree in Health Sciences at McMaster University in 2008. KEVIN W. EVA, PhD, is a senior scientist in the Centre for Health Education Scholarship, associate professor and director of Educational Research and Scholarship in the Department of Medicine at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. CARL B. DELOTTINVILLE, MSW, is an instructor in the Honours Bachelor of Health Sciences Program and an associate clinical professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences at McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. References Aspegren K. 1999. BEME guide no. 2: Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine-a review with quality grading of articles. Med Teach 21(6):563–570. Aspegren K, Lonberg-Madsen P. 2005. Which basic communication skills in medicine are learnt spontaneously and which need to be taught and trained? Med Teach 27(6):539–543. Back A, Arnold R, Baile W, Fryer-Edwards K, Alexandre S, Barley G, Gooley T, Tulsky J. 2011. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transition to palliative care. Arch Intern Med 167:453–460. Barry C, Bradley C, Britten N, Stevenson F, Barber N. 2000. Patients’ unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: Qualitative study. BMJ 320(7244):1246–1250. Boulet JR, David B, Friedman M, Ziv A, Burdick WP, Curtis M, Peitzman S, Gary N. 1998. High-stakes examinations: What do we know about measurement? Using standardized patients to assess the interpersonal skills of physicians. Acad Med 73(10):S94–S96. Butow P, Cockburn J, Girgis A, Bowman D, Schofield P, D’Este C, Stojanovski E, Tattersall M. 2008. Increasing oncologists’ skills in eliciting and responding to emotional cues: Evaluation of a communication skills training program. Psychooncology 17(3):209–218. Bylund C, Brown R, Gueguen J, Diamond C, Bianculli J, Kissane D. 2010. The implementation and assessement of a comprehensive communication skills training curriculum for oncologists. Psychooncology 19(6):583–593. Guiton G, Hodgson CS, Delandshere G, Wilkerson L. 2004. Communication skills in standardized-patient assessment of final-year medical students: A psychometric study. Adv Health Sci Educ 9(3):179–187. Haak R, Rosenbohm J, Koerfer A, Obliers R, Wicht MJ. 2008. The effect of undergraduate education in communications skills: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Dent Educ 12(4):213–218. Hodges B, Turnbull F, Cohen R, Bienenstock A, Norman G. 1996. Evaluating communication skills in the objective structured clinical examination format: Reliability and generalizability. Med Educ 30:38–43. Hulsman RL, Mollema ED, Oort FJ, Hoos AM, de Haes JCJM. 2006. Using standardized video cases for assessment of medical communication skills: Reliability of an objective structured video examination by computer. Patient Educ Couns 60(1):24–31. Humphris G. 2002. Communications skills knowledge, understanding and OSCE performance in medical trainees: A multivariate prospective study using structural equation modeling. Med Educ 36(9):842–852. Humphris G, Kaney S. 2000. The objective structured video exam for assessment of communication skills. Med Educ 34(11):939–945. Humphris G, Kaney S. 2001. Assessing the development of communication skills in undergraduate medical students. Med Educ 35(3):225–231. e249 Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 31.57.148.223 on 04/25/12 For personal use only. D. A. Baribeau et al. Knowles C, Kinchington F, Erwin J, Peters B. 2001. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of combining video role play with traditional methods of delivering undergraduate medical education. Sex Transm Infect 77:376–380. Kroboth F, Hanusa BH, Parker S, Coulehan JL, Kapoor WN, Brown FH, Karpf M, Levey G. 1992. The inter-rater reliability and internal consistency of a clinical evaluation exercise. J Gen Intern Med 7(2):174–179. Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. 2000. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. J Am Med Assoc 284(8):1021–1027. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, Ferrier K, Payne S. 2001. Preferences of patients for patient centered approach to consultation in primary car: Observational study. BMJ 322(7284):468–472. Makoul G. 2001. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: The Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med 76(4):390–393. Morse D, Edwardsen E, Gordon H. 2008. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Arch Intern Med 168(17): 1853–1858. Perera J, Mohamadou G, Kaur S. 2009. The use of Objective Structured SelfAssessment and Peer Feedback (OSSP) for learning communication skills: Evaluation using a controlled trial. Adv Health Sci Educ 15(2):185–193. Ruiz-Moral R, Perez Rodriguez E, Perula de Torres LA, de la Torre J. 2006. Physician-patient communication: A study on the observed behaviours of specialty physicians and the ways their patients perceive them. Patient Educ Couns 64(1–3):242–248. e250 Shaw J. 2006. Four core communication skills of highly effective practitioners. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 36(2):385–396. Simpson D, Gehl S, Helm R, Kerwin D, Drewniak T, Bragg D, Ziebert M, Denson S, Brown D, Gleason H, et al. 2006. Objective Structured Video Examinations (OSVEs) for geriatrics education. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 26(4):7–24. Stewart MA. 1995. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. CMAJ 152(9):1423–1433. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. 2008–2009. CanMeds best practice submissions, Ottawa: [Published 2010 June 20]. Available from: http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/bestpractices/ index.php Von Fragstein M, Silverman J, Cushing A, Quilligan S, Salisbury H, Wiskin C. 2008. UK council for clinical communication skills teaching in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ 42(11):1100–1107. Ward M, Sundaramurthy S, Lotstein D, Bush TM, Neuwelt CM, Street Jr RL. 2003. Participatory patient-physician communication and morbidity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arth Rheum 49(6): 810–818. Windish DM, Price EG, Clever SL, Magaziner JL, Thomas PA. 2005. Teaching medical students the important connection between communication and clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med 20(12):1108–1113. Yedidia M, Gillespie CC, Kachur E, Schwartz MD, Ockene J, Chepaitis AE, Snyder CW, Lazare A, Lipkin Jr M. 2003. Effect of communications training on medical student performance. J Am Med Assoc 290(9): 1157–1165.