Laboratory tests – Blood – Caroline Clark BVM&S BSc MRCVS

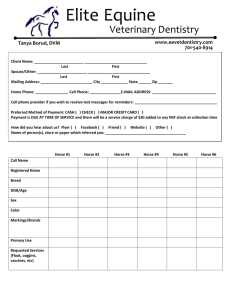

advertisement

Laboratory tests – Blood – Caroline Clark BVM&S BSc MRCVS If your horse is unwell we frequently cannot tell from an external examination alone what the cause of the problem is. We often advise taking a sample of blood, faeces or urine to try and investigate the problem further. This series of articles will hopefully explain what we are looking for when we advise you to have a laboratory test. This article will focus on blood tests. When we examine your horse, sometimes the changes seen at the examination alert us to test for a specific disease, e.g. long hairy coat in Cushings disease (PPID). With Cushings testing, the most usual test measures the resting level of a hormone (ACTH). The higher the level of ACTH, the more likely it is that the horse has Cushings. There is an expected level of hormone – known as the reference range – into which the ACTH concentration for normal horses would be found. More often, the signs the horse is exhibiting do not point us to a specific blood test, so we need to do a general screen to assess how the horse is responding to a disease. This usually gives clues as to what may be causing the problem, and how we should treat it. Components we test for include quantity and type of blood cells and enzymes found within the blood. Red blood cells Red blood cells are responsible for carrying oxygen around the body. If these are decreased, this is known as anaemia. Horses can be anaemic as a primary disease, but anaemia usually occurs as a result of another disease process in the body. If the anaemia is severe, it can be a cause of lethargy or poor performance in horses. White blood cells White blood cells are the cells that fight infection and give us a lot of information. They also increase in number when there is inflammation present. Inflammation can be caused by infections such as bacteria, viruses or parasites, but can also occur with tissue damage, such as traumatic injury, tumours or immune-mediated disease (where the body attacks itself). If your horse has a high white blood cell count it usually means that the body is producing more cells to fight the disease, whether that be an infection or in an area of inflammation. It is more concerning when we find that the white blood cells are decreased in number; this means that the body is trying to fight the disease but all the available white blood cells are already deployed in the body and supplies are running low. White blood cells come in different types – neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils and monocytes are the ones from which we get most information. Measuring the relative numbers of these cells is important, for example if neutrophils are low the horse may be suffering from a viral challenge, or if eosinophils are high, it is often associated with an allergic or parasitic response or disease in the intestine, skin or lungs. Neutrophils with red blood cells Eosinophils with red blood cells Proteins and enzymes Fibrinogen and serum amyloid A (SAA) are two proteins known as acute phase proteins that give us a useful measure of any inflammation present. SAA increases quickly and concentrations can rise to high levels, therefore it gives us a big range and is a sensitive indicator of inflammation. We often use SAA to monitor a disease or a response to treatment. Albumin is a protein made by the liver and levels often fall with inflammation. It is a key diagnostic factor in weight loss cases. If the levels are very low, it is likely the protein is being lost, for example into the gut or urine and this needs further investigation. Albumin levels can also decrease with liver disease, if the liver is not able to make enough. Liver enzymes include GGT, AST, GLDH and AP. Most of these are contained within liver cells. When there is liver disease present, the cells break down and release the enzymes into the blood, where they are seen to increase. These levels can give an indication as to how widely affected the liver is. Bile acids are used to assess the function of the liver – disease must be quite bad before this increase is seen. Kidney enzymes are creatinine and urea. These are released into the blood when there is damage to the kidney. Urinary system disease is best assessed when the blood is interpreted together with a urine sample (this will be discussed in a future article). Muscle enzymes – As for liver and kidney, muscle enzymes (CK and AST) are released when there is damage to the muscle, e.g. Above: Blood allowed to settle after being put into a if your horse suffers from exertional rhabdomyolysis (or tying tube. It has separated into up). Muscle enzymes can reach very high levels if large areas of cells, which sink to the bottom with gravity, and fluid muscle are damaged, and so are useful indicators for called plasma. monitoring when a horse can return to work following an episode of tying up. We send our blood samples to a laboratory in Hampshire that is situated within an equine hospital. The results are sent back to us and the blood sample is interpreted by considering all of the above components, together with the signs found on external examination. Blood samples give us clues as to the possible causes of disease, and tell us whether key organs like the liver or kidneys are involved, how badly the horse is affected and how the body is coping. The next newsletter will focus on faecal and urine tests.