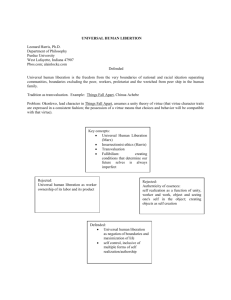

Latin American Liberation Philosophies: Analyzing Hugo

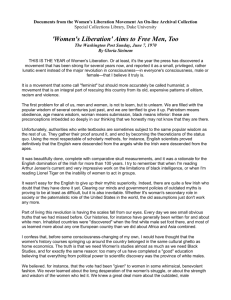

advertisement