Cycles and Clusters of the Millennial Hollywood Romantic Comedy

advertisement

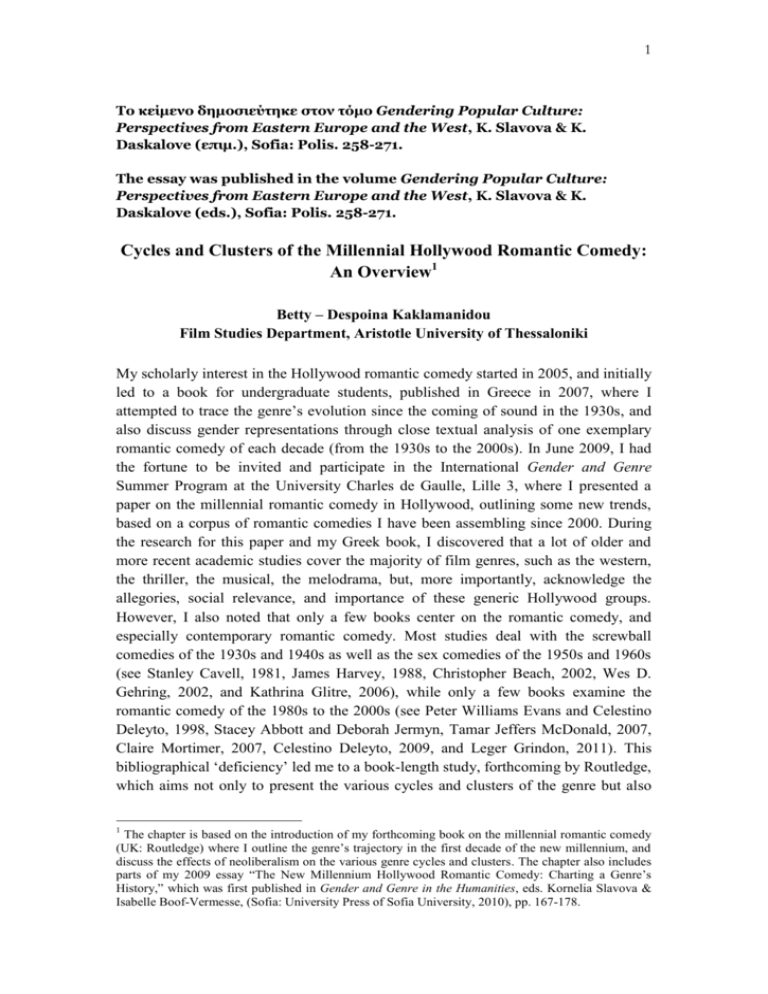

1 Το κείμενο δημοσιεύτηκε στον τόμο Gendering Popular Culture: Perspectives from Eastern Europe and the West, K. Slavova & K. Daskalove (επιμ.), Sofia: Polis. 258-271. The essay was published in the volume Gendering Popular Culture: Perspectives from Eastern Europe and the West, K. Slavova & K. Daskalove (eds.), Sofia: Polis. 258-271. Cycles and Clusters of the Millennial Hollywood Romantic Comedy: An Overview1 Betty – Despoina Kaklamanidou Film Studies Department, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki My scholarly interest in the Hollywood romantic comedy started in 2005, and initially led to a book for undergraduate students, published in Greece in 2007, where I attempted to trace the genre’s evolution since the coming of sound in the 1930s, and also discuss gender representations through close textual analysis of one exemplary romantic comedy of each decade (from the 1930s to the 2000s). In June 2009, I had the fortune to be invited and participate in the International Gender and Genre Summer Program at the University Charles de Gaulle, Lille 3, where I presented a paper on the millennial romantic comedy in Hollywood, outlining some new trends, based on a corpus of romantic comedies I have been assembling since 2000. During the research for this paper and my Greek book, I discovered that a lot of older and more recent academic studies cover the majority of film genres, such as the western, the thriller, the musical, the melodrama, but, more importantly, acknowledge the allegories, social relevance, and importance of these generic Hollywood groups. However, I also noted that only a few books center on the romantic comedy, and especially contemporary romantic comedy. Most studies deal with the screwball comedies of the 1930s and 1940s as well as the sex comedies of the 1950s and 1960s (see Stanley Cavell, 1981, James Harvey, 1988, Christopher Beach, 2002, Wes D. Gehring, 2002, and Kathrina Glitre, 2006), while only a few books examine the romantic comedy of the 1980s to the 2000s (see Peter Williams Evans and Celestino Deleyto, 1998, Stacey Abbott and Deborah Jermyn, Tamar Jeffers McDonald, 2007, Claire Mortimer, 2007, Celestino Deleyto, 2009, and Leger Grindon, 2011). This bibliographical ‘deficiency’ led me to a book-length study, forthcoming by Routledge, which aims not only to present the various cycles and clusters of the genre but also 1 The chapter is based on the introduction of my forthcoming book on the millennial romantic comedy (UK: Routledge) where I outline the genre’s trajectory in the first decade of the new millennium, and discuss the effects of neoliberalism on the various genre cycles and clusters. The chapter also includes parts of my 2009 essay “The New Millennium Hollywood Romantic Comedy: Charting a Genre’s History,” which was first published in Gender and Genre in the Humanities, eds. Kornelia Slavova & Isabelle Boof-Vermesse, (Sofia: University Press of Sofia University, 2010), pp. 167-178. 2 demonstrate the connection between this ‘light’ generic category of films to the sociopolitical climate it is produced in. This chapter will therefore introduce the diversity and variety that the romantic comedy genre presents in the first decade of the new millennium. It has been already stated that the Hollywood romantic comedy is regarded as an ‘inferior’ film genre by both the Press and many scholars due to a variety of reasons. Replaced more than often by the slang noun ‘chick flick’, which implies its audience consists exclusively of female viewers, it is also accused of maintaining a superficial and highly conventional narrative formula. The main arguments ‘against’ the millennial Hollywood romantic comedy films include the representation of a utopian cosmos, the genre’s ‘inability’ to address societal issues, and its narrative predictability which mainly refers to the more than often happy ending. However, I believe that these assumptions deserve a more careful approach. First, I will begin by admitting the obvious; by definition, romantic comedies focus on romantic relationships, ‘sprinkled’ with a dose of comic situations, in a middle to upper-class milieu, where money is almost never an issue. Nevertheless, it would be hasty to argue that these texts are unable to provide social commentary. Comments regarding the lack of sociopolitical critique do not accompany, for instance, the screwball comedies of the 1930s and 1940s whose protagonists are rich, whose settings are luxurious mansions and whose costumes are lavish. For example, My Man Godfrey (1936) narrates the story of a spoilt Fifth Avenue socialite who changes gowns in every scene while her mother and sister are only interested in parties and fun. Similarly, The Philadelphia Story (1940) revolves around one of the wealthiest heiresses of Philadelphia while the setting is an estate against which the majority of the stylish New York apartments featured in millennial rom coms would simply pale in comparison. Nevertheless, the screwball comedy is considered today as a paradigmatic instance of not only the romantic comedy genre but also of class articulation, and astute social observation (see for example Beach and Gehring). Even though most of the screwball comedies of the 1930s and 1940s include criticism against the upper classes, they do so in a comic and more than often subtle manner. In addition, I would argue that the ‘hypothetical’ exclusion of explicit sociopolitical commentary in the contemporary rom com does not imply its absence. Every cinematic text, irrespective of generic boundaries, is a product of a specific societal environment and carries the ideological stamp of the filmmaking team. Barry Keith Grant observes that “[p]opular culture does tend to adhere to dominant ideology, although this is not always the case. Many horror films, melodramas and film noirs, among others, have been shown to question if not subvert accepted values” (33). As a result, the millennial romantic comedy cannot be discarded a priori as a mere product of a neoliberal society which seeks profit irrespective of content. On the one hand, there are contemporary romantic comedies which reflect this socioeconomic climate but there are many examples of cinematic texts which criticize, assess, and/or propose 3 alternatives to the dominance of neoliberalism, and/or the representation of a ‘gendered’ status quo. Furthermore, the quantity and diversity of the genre’s production in the first decade of the new millennium cannot lead to a single conclusion since even films that were shot and/or released in the same year incorporate contradicting views on societal issues. Furthermore, like their cinematic precursors, contemporary Hollywood romantic comedies are popular texts that can have multiple readings. First, they explore issues of intimate relationships, friendship (male-male, female-female, male-female) marriage, and work and as such they may serve as conveyors of helpful paradigms and/or food for thought for the global audience as they allow reflection “upon romance as a personal experience and a social phenomenon” (Grindon 2). Despite the insistence on the union of the heterosexual couple at the end of the narrative, I would claim that it can be more productive “to move away from the Althusserian determinism that still pervades much contemporary generic criticism and towards a view of genre as culturally and historically mediated” (Deleyto 18). Deleyto argues that most of the time, critics and scholars alike tend to evaluate a romantic comedy based on its ending – which mainly consists of the heterosexual union, and/or reunion –, thus validating its conservative nature, and also ignoring the main body of the narrative where subversive and/or progressive elements are often included. Lastly, it should be noted that there are millennial texts that end with two single people, such as Prime (2005), The Break-Up (2006), and (500) Days of Summer (2009), which “suggest[s] that the final separation of the lovers is becoming more and more usual as part of the happy ending” (Deleyto 25). The third argument against the genre regarding its narrative predictability can be applied to every genre, since from acclaimed dramas to sci-fi, horror films, and comedies, the three-act structure, the character-driven plot, and the final dénouement irrespective of the form it may take (from the death of the villain, and/or monster in the action, and horror films to the catharsis in the drama) are conventions the audience is expecting and is always looking forward to watching. What is more, there are also romantic comedies that surprise and/or play with the conventions by either ending with the two main characters apart (The Break-Up), by hinting at the possibility of a new relationship which has not been consummated (It’s Complicated), and/or by following a non-linear narrative ((500) Days of Summer). In addition, the several instances of intertextuality that are present in many contemporary cinematic texts can be considered as enriching and assisting the evolution of the genre. Gérard Genette (7) uses the term “transtextuality”, influenced by Mikhail Bakhtine’s concept of “dialogism,” and Julia Kristeva’s “intertextuality,” to refer to anything that “puts a text in an overt or covert relation with other texts.” For example, when Jake (Alec Baldwin) tries to get back with his wife Jane (Meryl Streep) in It’s Complicated (2009), he rents the classic romantic comedy The Graduate (1967) for the whole family to enjoy at home. The use of shots from such popular films as The Graduate and Jerry Maguire (1996) in films such as It’s Complicated, Hitch (2005), and (500) 4 Days of Summer serve a double function; first they engage the older audience in a playful game of irony, but also introduce the younger viewers to significant genre films of the past. Finally, romantic comedies are frequently undervalued as exclusively addressing the female audience. However, if we treat the genre as a narrative that places a woman or a girl at the center, then the genre itself instantly becomes the ‘Other’ to a norm that is never explicitly articulated in the Press. On the one hand, no one ever writes that male-centered blockbusters, and/or male-centered dramas are the canon to which the female-centered rom coms should compare. On the other hand, nowhere is it mentioned that male-driven films target their own specific audience. It is therein that a social and at the same time theoretic impasse lies; for as long as one keeps separating female cinematic narratives from an established but unnamed ‘norm,’ the dichotomy between the dominant/male and the submissive /female films will regrettably be carried on. At the same time, this disparity will keep producing academic work which strives to examine the genre in detail and show that the close reading of these films may assist the emergence of complex meanings that not only address gender politics but also provide a societal, however hidden and subtle, critique. Nevertheless, despite its mostly negative reputation, the last three decades witnessed a steady increase in the numbers of romantic comedies, which positions the genre among the most popular ones in the globally dominant Hollywood film industry. Since the genre’s film production is still thriving in the second decade of the 21st century, it is only natural if not imperative to keep on investigating its evolution through the creation of new cycles as well as the readjustment or maintenance of old formulae as recent research confirms that the genre “will survive by adapting to changing historical circumstances” (Evans and Deleyto 1). The identification of the cycles and/or clusters is based on a corpus I have assembled which includes 161 Hollywood romantic comedies produced in the U.S.A. and released domestically and worldwide from 2000 to 2010. The criteria used for the compilation of the films were the following: first, each film text had to be classified as a romantic comedy by at least two sources – which include the two major internet databases imdb.com and boxofficemojo.com as well as reviews from major publications such as the New York Times and/or the Chicago Sun-Times –. Second, my exclusive focus on Hollywood productions excludes by definition several popular both commercially and/or artistically acclaimed romantic comedies, such as the British Bridget Jones’ Diary (2000), Love Actually (2003), and Bridget Jones’ Diary: The Edge of Reason (2004), in addition to such US productions as Brown Sugar (2002), Breakin’ All The Rules (2004), and Just Wright (2009), which target the African-American niche audience and were not distributed internationally. Third, and most importantly, however, the ‘dominant’ feature of all the rom coms had to be the pursuit of love by two individuals couple combined with a lot of comic moments. According to the Russian formalist, Roman Jakobson (751), “[t]he dominant may be 5 defined as the focusing component of a work of art: it rules, determines, and transforms the remaining components.” It is “the element which specifies a given variety of language [or any narrative element] dominates the entire structure and thus acts as its mandatory and inalienable constituent dominating all the remaining elements and exerting direct influence upon them”. Thus, also absent from the corpus are films that may be considered as romantic comedies by the Press, such as Bride Wars (2002), I Love You Man (2009), and Morning Glory (2010), among others, because the dominant features are female friendship, male bonding, and career orientation respectively, while the romantic relationships of their protagonists are included in a subplot. Although I cannot argue that the corpus is exhaustive, I believe it provides a comprehensive starting guide of the genre production in the first decade of the new millennium and can serve as a valuable methodological tool from which a number of interesting conclusions will be drawn. First, the corpus confirms the continuing popularity of the genre in the beginning of the 21st century; the numbers of films may fluctuate from 11 in 2006 (the lowest) to 19 in 2009 (the highest), but the average number of 14,7 demonstrates that the genre is among the film industry’s production priorities. The second observation confirms that male power is dominant in what is mainly considered a female genre. From the 124 directors of the 160 films, only 16 were women (13%), and directed only 20 films (12,4%). An improvement was observed in the writing department as 53 (32,7%) romantic comedies were written or co-written by female writers. It should be noted, however, that this obvious gender inconsistency does not only concern the genre in question but unfortunately constitutes a norm in the film industry. According to a study by the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film “women made up 18 percent of all directors, producers, writers, cinematographers and editors working on the top 250 highestgrossing movies” in 2011 (Rebecca Ford). Although, these numbers are certainly unsatisfactory, a more thorough discussion on the role that women play in film production and distribution exceeds the goal of this essay book and should be set aside for future and I might add necessary academic study. After these preliminary remarks, I divided the corpus into nine major cycles and clusters. Cycles are group of films that surface within a film genre once the film industry feels it can capitalize “on the (often unexpected) success of a specific film that offers a new twist on an old genre” (Glitre 20), by investing in similar cinematic texts films that include what Rick Altman calls “common features.” For instance, the “new career woman” cycle of the new millennium focuses on a group of films whose fundamental narrative device is how the heroine manages her professional ambitions in relation to her love life. On the other hand, the term ‘cluster,’ used by Grindon defines an assemblage of films that do not include “a coherent model or common motifs among productions from the same period” (25), yet they share a major thematic, and/or narrative ingredient. For instance, the cluster I call the ‘man-com’ 6 may include diverse in theme, tone, and narrative structure romantic comedies; yet all the films are narrated by a central male point of view. The first cycle is the ‘battle of the sexes’ cycle, which has had a long history starting with the screwball comedies of the 1930s. However, the Hollywood film industry still continues to produce rom coms that focus on the stereotypical differences that are thought to exist between men and women and try to impose the perception that men are indeed from Mars and women from Venus. The ‘dominant’ element of these romantic comedies is the witty verbal exchange targeted mainly at the differences of the sexes between the hero and the heroine who begin their narrative journeys as enemies of some sort only to end up together and in love. This cycle comprises films such as Someone Like You (2001), Down With Love, Intolerable Cruelty, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days (all three 2003), and Leap Year (2010). The palpable tension and hostility that are at first created between the man and the woman constitutes a fruitful ground for the examination of whether or not the two sexes actually long for different things regarding love, commitment, relationships and marriage. At the same time, these millennial rom coms place their protagonists in either the same working environment, and/or make them rivals of some sort, therefore creating tensions that have to do with professional ambitions in a neoliberal climate which promotes individualism and consumerism. Thus, although the battle of the sexes almost always ends with a ‘truce,’ it also provides interesting conclusions as to the part played by the surrounding socio-economic climate in the formation and/or the endurance of the millennial romantic relationship. The origins of the second cycle go back to another popular 1940s genre cycle; the career woman comedy (His Girl Friday, 1940, Adam’s Rib, 1949). The ‘new’ career woman comedy, which includes such films as The Wedding Planner (2001), Life, or Something Like It (2002), Two Weeks Notice (2002), View From the Top (2003), New in Town (2009), and The Proposal (2009) initially portray the modern career woman as neurotic, and misguided. The narrative often charts how the life of this careerfocused heroine becomes disrupted by the male protagonist. Although the happy ending can easily lead to the conclusion that the heroine’s professional aspirations were just the wrong path and that what is really ‘important’ in life is love, marriage and a family, it is interesting to note, once again, how most endings of this cycle’s films preserve the professional identity of the heroine and propose that female career ambitions can accompany a healthy romantic relationship. The third cycle is the fantasy romantic comedy, yet another generic category whose history can be traced back to the 1930s and Topper (1937), the screwball romance, whose protagonistic couple, the Kerbys (Constance Bennett and Cary Grant), die in a car accident, become ghosts, and decide to make the most of this unfortunate situation. The combination of fantasy and magic (13 going on 30, 2004, Bewitched, 2007, When in Rome, 2010), super powers (My Super Ex-Girlfriend, 2006), the afterlife (Just Like Heaven, 2005, Over Her Dead Body, 2008, Ghost Town, 2008), and fairy tales and animation (Ella Enchanted, 2004, Enchanted, 2007) produces 7 hybrid romantic comedies with a twist. Billy Mernit (27) underlines that in this hybrid cycle, “the conflicts revolve around issues typical of the genre norm” whereas “climaxes often involve an obligatory “recognition” scene” (i.e., Jack (Will Ferrell) finally realizes that Isabel (Nicole Kidman) is a witch in Bewitched, or when Jenny (Uma Thurman) reveals to Matt (Luke Wilson) that she is in fact a super-heroine). Nevertheless, leaving the palpable escapist side of these narratives aside, the ‘dominant’ feature is still the search for love. By “bending reality” (Mernit 28), these rom coms create a world where love is always a possibility and can beat even death. At the same time, however, the fantasy element “frame[s] social reality” (Joshua David Bellin 9). Therefore, these hybrid rom coms are socially relevant insofar as they “function as mass-cultural rituals that give image to historically determinate anxieties, wishes, and needs,” and “simultaneously function by stimulating, endorsing, and broadcasting the very anxieties, wishes, and needs to which they give image.” (ibid). The fourth cycle is a relatively new one as its cinematic life started in 1984 with the release of Romancing the Stone. Films such as Serving Sara (2002), Fool’s Gold (2008), The Bounty Hunter, Killers, Date Night and Knight and Day (all released in 2010) combine action/adventure with romance to provide pleasure to both female and male viewers. These narratives assist the examination of the dynamics of the heterosexual couple who are faced with extremely dangerous situations. Whether the couple is already married (Fool’s Gold, Date Night and Killers) or has just met (Knight and Day) it is interesting to see whether the female assumes a passive or active role and/or acts as an equal to her male counterpart. It should be noted that during the end of the 1990s as well as the new millennium a significant number of female heroines and/or super-heroines emerged in both television and film; shows such as Alias (ABC, 2001-2006), Charmed (WB, 1998-2004), and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (WB, 1997-2003), and films such as the two Lara Croft and Charlie’s Angels installments, Underworld (2003), Catwoman (2004), Aeon Flux (2005), and Elektra (2005) were ruled by super female strength and resourcefulness, and proved that women are as competent as men to undertake any type of perilous mission. In addition to this analysis of female active participation in the face of danger, the action romantic comedy offers many instances of male objectification, thus demonstrating that the cinematic gaze is not exclusively male, but can also be female, and/or LGBT. The fifth cycle is the teen romantic comedy which, interestingly enough, consists of films whose central character is a teenage girl, perhaps following the rise of the Girl Power movement and its constant presence and/or propagation in media culture for the past two decades. Films such as Get Over It (2001), Chasing Liberty (2004), and Sydney White (2007) not only address adolescence, which in almost every respect (from personality development, to the acquisition of tastes in music, fashion, cinema, educational abilities, and sexual identity among others) is one of the most important periods in the life of an individual, but also provide valuable food for thought for an entire society system. Since most of these films take place in the US school system, 8 which can be compared to society at large, if one is to take into account the different ‘categories’ students belong to (the jogs, the cheerleaders, the nerds, the artists, etc.), then the teen romantic comedy can be used to unearth the critique included in the narrative against the inequalities and injustice that exist in a larger societal scale. Cycle six, the “of a Certain Age” cycle is a ‘new entry’ in the romantic comedy cosmos and constitutes a most welcome addition to the genre. The films of the cycle renegotiate gender roles by investing in mature protagonists. Either exploring a reversed May-December romance (Under the Tuscan Sun, 2003, Prime, 2005, Sex and the City, 2008, The Rebound, 2010), marital problems (Trust the Man, 2006, Couples Retreat, 2009), or the re-birth of romantic and/or sexual vitality (Something’s Gotta Give, 2003, It’s Complicated, 2009), these romantic comedies depict how the millennial mature woman, who more than often has already had marriage and children, finds herself in a new chapter, where romance is discovered, or rediscovered. Cycle seven is a group of films that center on a new narrative stratagem and therefore constitutes a new cycle; in the ‘baby-crazed’ romantic comedies, such as Baby Mama (2008), The Back-Up Plan, and The Switch (both 2010), the narrative revolves around the heroines’ initial decision to experience motherhood without a partner. By placing motherhood before romance, because the heroines are considered ‘unlucky’ in the love department and/or because their age and the infamous biological clock leave them no choice but to take matters into their own hands, these films become not only socially relevant but assist the evolution of the genre at the same time as the introduction of a sperm donor, and/or a surrogate mother, offers the possibility for a new syntax in the genre’s structure. However, even though it can be argued that these narratives celebrate the third feminist wave’s emblem of ‘choice,’ a number of significant issues arise when the question turns from a woman’s desire to become a mother to the possibilities offered to her to do so without a partner. Whether the heroine chooses an unknown donor, or a surrogate, it becomes clear that a substantial amount of money has to exchange hands. Thus, the baby-crazed romantic comedies not only address motherhood as a desire but also hint at the neoliberal insatiable need for profit that can even turn life into another form of commodity. The next group of romantic comedies is the cluster that I call the ‘man-com.’ Although the romantic comedy genre is almost invariably labeled female, the data provided by the corpus not only confirmed that the greatest percentage of romantic films are produced and created by men but a surprisingly important percentage is also focused on male protagonists. The man-com cluster includes diverse films whose ‘dominant’ element is that they are filtered through a male perspective. These romantic comedies can be further divided into the following cycles: the ‘Peter Pan’ cycle includes films such as What Women Want (2000), The Bachelor (2000), 40 Days and 40 Nights (2002), Wedding Crashers (2005), Hitch (2005), Failure to Launch (2006), A Good Year (2006), Made of Honor (2008), and Ghosts of 9 Girlfriends Past (2009) focus on a ‘man’s man,’ respected by his male friends, adored by women, and highly successful professionally. The ‘neurotic’ cycle comprises the recent Woody Allen’s films, such as Hollywood Ending (2002), Anything Else (2003), and Whatever Works (2009), but also films such as Along Came Polly (2001), and Sideways (2004), which examine male neuroses and usually place the female lead in the role of the male psyche healer. Finally, the ‘high-maintenance’ cycle is made up of films such as Me, Myself & Irene (2000), Shallow Hal (2001), About a Boy (2002), The 40 Year-Old Virgin (2005), Dan in Real Life (2007), and Ghost Town (2008), which revolve around 30 or 40-something men with various emotional troubles. It becomes clear that the man-com cluster present different types of masculinities, which depending on the films’ release year may or may not adhere to the prevailing masculinity model of the Bush administration. More importantly, however, the different representations of male behavior towards life, career, and love show how the concept of a single masculinity model is not an adequate theoretic tool and should also be always examined with regard to the specific sociopolitical context of its representation. The corpus included mainstream Hollywood romantic comedies, which by definition exclude the great number of independent productions that provide interesting insights as to the paths the romantic comedy genre can take. That is why, cluster nine is devoted to those independent romantic comedies, which assist the evolution of the genre as well provide alternatives to gender performativity. In 2002, Frank Krutnik remarked that in the early 1980s, the Hollywood romantic comedy “has been remodeled for niche audiences defined by ethnicity, sexual orientation or age” (130). For instance, the independent, low-budget productions Kissing Jessica Stein, (2001), Gray Matters (2006), and Puccini For Beginners (2007) destabilize the omnipresence of the central heterosexual couple and focus on same sex love and strong friendships between women despite the fact that the grammar of the genre has dictated for many decades that the mainstream cinematic love stories always involve white, heterosexual and middle to upper class characters who struggle to find love in the urban jungle of each time period. The ‘women who love women’ cycle does indeed include white and bourgeois heroines but it puts forward their bisexual and/or homosexual identity. This change in grammar results in a number of syntactic alterations which may include “plot structure, character relationships or image and sound montage” (Altman 89). Character relationships are indeed altered in these lesbian romantic comedies and lead to quite significant narratives, if considered in a wider social context. These films achieve to become sites of contestation for lesbian anxiety and representation as they view desire as solely based on the individual rather than a socially, ideologically and ethically constructed mechanism and they stress the difficulties homosexuality and/or bisexuality pose to their heroines, even if they do it in the safe world of the romantic comedy, in which no-one expresses an overtly homophobic opinion. According to Altman (26) “genre films […] maintain a strong connection to the culture that produced them” and “film genres are functional for their society.” If we 10 associate Altman’s view with the aforementioned charting of the various cycles and clusters of the romantic comedy genre in the first decade of the new millennium, we could conclude there is an attempt to uphold the societal status quo, but at the same time, there are signs of progression and subversion. Finally, if one is to take the sociopolitical climate of the same period into consideration, as well as the supremacy of neoliberalism, some interesting points could be put forward. The George W. Bush administration (2001-2009), the 9/11 attacks, the subsequent War on Terror and the fear, the government spread to the U.S. through the media gave rise to a new-found conservatism and a need to return to the family core and embrace traditional values. However, the 2008 global recession, and the first African-American President in 2009 brought about changes whose consequences cannot be thoroughly examined until a substantial historical distance is attained. Therefore, the romantic comedies as popular texts, produced and released during the 2000-2010 period provide an invaluable terrain for the investigation of not only gender representations and the obvious limitations of the strict femininity/masculinity but also of the existing and significant correlations between romantic relationships and the neoliberal regime. Works Cited Abbott, Susan and Deborah Jermyn, eds. Falling in Love Again, Romantic Comedy in Contemporary Cinema. UK: I. B. Tauris, 2009. Altman, Rick. Film / Genre. UK: BFI, 2006, 2004, 2003, 2002, 2000, 1999. Beach, Christopher. Class, Language and American Film Comedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Bellin, Joshua David. Framing Monsters: Fantasy Film and Social Alienation. USA: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005. Cavell, Stanley. Pursuits of Happiness. USA: Harvard University Press, 1981. Evans, Peter Williams & Celestino Deleyto. “Introduction: Surviving Love”. Terms of Endearment. Hollywood Romantic Comedy of the 1980s and 1990s. Eds. Peter Williams Evans & Celestino Deleyto. UK: Edinburgh University Press, 1998. Deleyto, Celestino. The Secret Life of Romantic Comedy. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009. Ford, Rebecca. “Fewer Female Directors Worked on Top Films in 2011.” The Hollywood Reporter, 24 January 2012. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/women-directors-film-study-284321, accessed January 26 2012. Gehring, Wes D. Romantic vs. Screwball Comedy: Charting the Difference. USA: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2002. Genette, Gérard. Palimsestes: La littérature au second degré. Paris: Seuil, 1982. Glitre, Kathrina. Hollywood Romantic Comedy. UK: Manchester University Press, 2006. Grant, Barry Keith. Film Genre. From Iconography to Ideology. UK: Wallflower Press, 2007. 11 Grindon, Leger. The Hollywood Romantic Comedy. UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. Harvey, James. Romantic Comedy in Hollywood: from Lubitsch to Sturges. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998. Jakobson, Roman. Selected Writings III: Poetry of Grammar and Grammar of Poetry. The Hague: Mouton, 1981. Jeffers McDonald, Tamar. Romantic Comedy. Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. UK: Wallflower, 2007. Kaklamanidou, Betty-Despoina. “Queering the Romantic Comedy: The ‘Women who Love Women’ Cycle”. Jura Gentium Cinema, http://www.jgcinema.org/pages/view.php?cat=articoli_dossier&id=370&id_film=161 &id_dossier=22. 2009 Krutnik, Frank. “Conforming Passions? Contemporary Hollywood Comedy”. Genre and Contemporary Hollywood. Ed. Stephen Neale. London: British Film Institute, 2002, 130-147. Mernit, Billy. Writing the Romantic Comedy. New York: HarperCollins, 2000. Mortimer, Claire. Romantic Comedy. UK: Routledge, 2010.