Undocumented and Acting Up - UCLA Department of Political Science

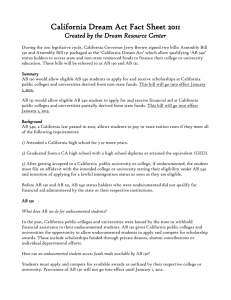

advertisement