Automatic Enrollment Strategies

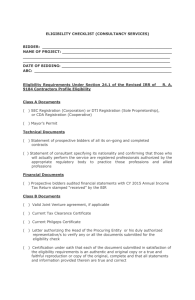

advertisement