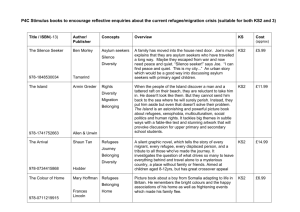

After Wilberforce: an independent enquiry into the

advertisement