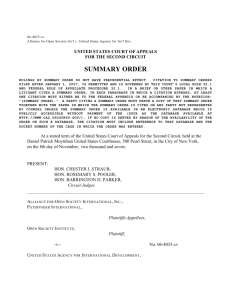

reconciliation after winter: the standard for preliminary

advertisement