HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 1 Strategic Management and

advertisement

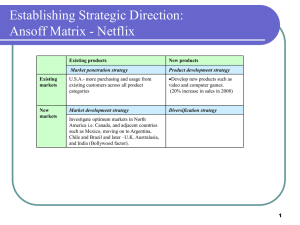

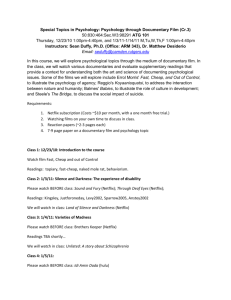

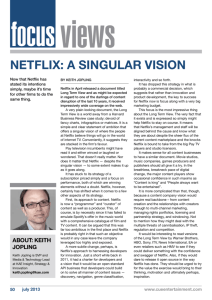

HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER Strategic Management and Organizational Culture: How Netflix Survived Disaster Michael Doughty Lethbridge College Nov. 4, 2013 For Cheryl Meheden BUS 1170 Introduction to Business Management 1 HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 2 Abstract Netflix is the world’s leading provider of streaming media. In 2011, the company made a strategic error that almost resulted in bankruptcy. This paper explains how Netflix survived a devastating loss of consumer and investor confidence by examining the strategic mistakes the company made and the three driving elements of its recovery: innovation, leadership, and a strong organizational culture. The Netflix organizational model provides a framework for building successful and resilient organizations in the digital age. HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 3 Strategic Management and Organizational Culture: How Netflix Survived Disaster Netflix is a company founded on innovation and visionary leadership. Since their initial public stock offering in 2002, the company has experienced a virtually uninterrupted run of success and growth. Along the way, they have bankrupted competitors, developed new technologies for content delivery, and changed the way people consume entertainment. One misstep, however, nearly ruined Netflix. Their remarkable recovery stands as an example of how strategic management, and its connection to building strong organizational culture, is a critical factor in the digital marketplace. The Decision In 2011, Netflix conducted an external analysis of the marketplace and determined that emerging technologies such as smartphones and tablets would radically alter the way consumers accessed digital media. They made the decision to spin off the highly profitable but low growth mail-order DVD business into a new company called Qwikster. The reasoning behind the decision was sound: diversification would allow Netflix to focus on the less profitable but rapidly growing streaming business they pioneered, financed by revenues from DVD delivery. The two companies would essentially compete against one another, allowing consumers the opportunity to choose the delivery method that best suited their needs. Netflix was observing the principles of the BCG Matrix (Robbins, Coulter, Leach, & Kilfoil, 2012, p. 218). The BCG Matrix demonstrates how growth oriented organizations need to focus on businesses that offer the potential for high growth and high market share. Spinning off HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 4 the DVD business would afford Netflix the opportunity to grow online streaming from a small market share into a potential giant. What Went Wrong On July 12, 2011, Netflix announced their plan to the public. Netflix would separate DVD rentals and streaming into two companies. Customers wanting both services would now pay $15.98 per month, a sixty percent increase (Gilbert, 2011). People affected by the sudden price increase expressed their anger, and Netflix lost over one million subscribers over the next three months. On November 25, 2011, shares of Netflix were trading at $63.85 (Figure 1, Netflix Stock Price, July 7, 2011 - Oct. 31, 2012, Google Finance, 2013). One analyst declared Netflix “broken…and suffering nuclear winter” (McMillan, 2011). Others later dubbed the move “Apocaflix.” What happened? Netflix failed to implement their strategic shift in a way that customers could understand. Miller (2007) outlines several factors important to implementing a new strategic decision. In particular, the concept of cultural receptivity refers to the willingness of a group of people to accept sudden or dramatic change. Change not properly communicated to its intended audience is difficult to accept or maintain. Put another way, Robbins, et al. (2012) describe a method for reducing resistance to change using the concept of unfreezing and refreezing in order to implement change. While their example pertains to organizational changes, it applies equally to changes that affect an organizations external environment. Netflix implemented their decision without clearly explaining the reason for the change, and did little to explain the benefits to consumers. The HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 5 fallout in the months after the announcement simply reinforced the idea in consumers’ minds that Netflix was trying to gouge them for profit instead of providing a valuable new service. The original Netflix subscription of $9.99 per month included unlimited DVD rentals and streaming movies online. Consumers compared the Netflix price point to competitors like Blockbuster and saw considerable advantages. No late fees, door-to-door delivery, and a broad selection of titles were the cornerstones of Netflix early success. In marketing, this is perceived value: the amount a consumer is willing to pay for a product after considering all the benefits (Kerin, Hartley, Rudelius, Clements, & Skolnick, 2012). Loyal Netflix customers were evidently willing to pay the original price, but that value disappeared when they were asked to pay almost double the price with less perceived benefit. Customers quickly found alternatives such as Hulu, Amazon Prime and other on-demand content providers to satisfy their demand. Netflix had failed to anticipate their customer’s unwillingness to change, being entirely focused on online streaming. The company still saw Qwikster as a viable operation, and proceeded with their plans in early September, 2011. By September 18, 2011, Reed Hastings issued a public apology via the Netflix website, clarifying why Netflix had made the decision and attempting to assuage consumer’s anger and confusion (Hastings, 2011). Critics quickly dismissed the apology as half-hearted and reactionary, while the exodus of subscribers continued (Loftus, 2011). Figure 1.1 shows the initial effect of the Qwikster announcement on Netflix share price. HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 6 07/13/11, $298.73 11/25/11, $63.86 9/25/12, $53.80 Figure 1, Netflix Stock Price, July 7, 2011 - Oct. 31, 2012 Retrenchment vs. Repositioning Netflix was now in full reverse. Their customers were leaving for competitors and investors were furious. Braun & Latham (2012) describe retrenchment as “any activity intended to reduce organizational costs or assets and boost operational efficiency” (p. 15). While it is obvious that Netflix was hemorrhaging money and subscribers, they chose not to downsize or replace their senior management. Both would be viable tactics used by companies experiencing rapid decline. After issuing his apology, Hastings and his team refocused their efforts on repositioning Netflix as a streaming entertainment company that also delivered DVD’s by mail. “Repositioning…entails return-to-growth initiatives such as market penetration, product innovation, new market entries, alliances and acquisitions and other longer-term actions that sharpen the company’s competitive edge” (Pearce & Robbins, 2008). Netflix first attempts at repositioning proved disastrous. Qwikster was scrapped within three weeks. An attempted partnership with content provider Starz fell through. A year after the repositioning began Netflix stock, after some recovery, had fallen to $53.80 (Google Finance, 2013). HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 7 According to Braun and Latham (2012), companies faced with turning around a failing enterprise have four possible outcomes. They can collapse by not reacting soon enough to environmental change, then doing too little, too late to reverse their decline. Netflix early competitor Blockbuster is an example of this. Companies can be set adrift by focusing too much on shoring up their financial losses and not addressing their need to change and grow. We see this in the slow recovery of the auto industry after the market collapse of 2008. Running on empty is the opposite, where a company does nothing to shore up their financial losses and proceeds with expansion anyway, as demonstrated by the Canadian firm Research In Motion, makers of Blackberry. A company that executes an effective turnaround balances retrenchment and repositioning equally and makes a comeback. Figure 2, Four Outcomes of Retrenchment & Repositioning (Braun & Latham, 2012) illustrates this concept. Figure 2, Four Outcomes of Retrenchment & Repositioning (Braun & Latham, 2012) Strategic Flexibility Why do some companies manage to recover from decline while others lose their competitive advantage or simply disappear? Much of Netflix’ post-Qwikster recovery has to be attributed to the organization Hastings began building in 1997. Companies that pull off a HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 8 successful comeback possess three critical elements that allow them to persevere: Disruptive Innovation, Visionary Leadership, and a flexible Organizational Culture. Disruptive Innovation The term disruptive innovation refers to “a product or service (that) takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves up market, eventually displacing established competitors” (Bower & Christensen, 1995). Early examples of disruptive technologies include personal computers that eliminated typewriters and revolutionized business; cell phones that replaced home phones; and digital photography, which has virtually replaced chemical film development. Figure 3 Disruptive Innovation [.gif] (Wikipedia, 2005) illustrates how disruptive technologies affect a market. Figure 3 Disruptive Innovation [.gif] (Wikipedia, 2005) While Netflix was not the first company to offer real-time video streaming online, they developed a proprietary system that consumers preferred and for which they were willing to pay a subscription. When Netflix decided to separate streaming and DVD delivery, consumers perceived this as losing a service. What Netflix understood but failed to communicate was that online content streaming was the future of media delivery. Computers, tablets, and smartphones HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 9 have largely replaced the DVD format, allowing customers to view selected media without the need for a plastic disc. Richardson (2011) argues that being the first mover to shift from DVD delivery to online streaming represented a disruptive innovation, one that consumers did not initially appreciate and which Netflix competitors have yet to match. Disruptive technologies create a tipping point in the marketplace more significant than new product innovations. Netflix has fundamentally altered how we access, purchase, store, and engage with entertainment. Although customers initially abandoned Netflix to express their displeasure with the Qwikster decision, they have swarmed back in recent quarters. When presented with alternatives, customers chose to return to Netflix. What they offer is too valuable to ignore. Visionary Leadership Being ready to respond and take advantage of change when it occurs is largely the result of visionary leadership. “…strategic vision is part style, part process, part content, and part context, while visionary leadership involves psychological gifts, sociological dynamics, and the luck of timing. True strategic visionaries are both born and made, but they are not self-made. They are the product of the historical moment.” (Westley & Mintzberg, 1989, p. 21) As discussed previously, Netflix senior management knew that the shift to streaming content had to happen eventually, the only question was when. They saw the emergence of new technologies that could increase their reach and make Netflix accessible to hundreds of millions of consumers. While their announcement may have been misguided, the reasoning behind the HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 10 decision has proven sound. Seeing a coming trend and being in the best position to capitalize on it is one definition of visionary leadership. Visionary leadership also describes the types of activities in which managers are engaged. “(visionary leaders are) tuned into the internal and external environment, the source of the vision; (they) mobilize support for the vision, though a process of networking; be visible to those they lead, as well as listening to, involving and developing them; build effective teams, bringing together people with complementary qualities and areas of expertise, clarifying and agreeing team goals and individual responsibilities, and working interdependently to achieve those goals.” (Manning, 2012) When we think of visionaries, we often speak of an individual. Organizations can also be visionary in their strategic thinking, flexibility, and ability to adapt to change. With Netflix, we may also add the ability to persevere and pursue a vision, even when all indicators suggest failure. By November 2011, analysts and investors were demanding change. Qwikster was abandoned, but few changes were made in senior management. Hastings and his team were now tasked with seeing their vision through to fruition. HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 11 Organizational Culture “Average performance is rewarded with a generous severance package.” Reed Hastings All of the innovation and leadership Netflix displayed would have been useless if the organization was not built to withstand change. Netflix is a dynamic, adaptable organization structured specifically to compete in the digital age. Robbins, et al. (2012) would describe Netflix organizational structure as highly organic. Organic organizations are less formal that traditional models, made up of cross-functional teams with a high degree of employee empowerment. The flexibility and creativity that allowed Netflix to pull through such a difficult time in its history is directly attributable to the way the company hires and organizes its staff. Hiring In 2009, a document was posted on Netflix website entitled “Netflix Culture: Freedom and Responsibility” (Hastings, 2009). It outlined the organizational culture of Netflix, listing seven components important to Netflix goal. Most important of these to the Netflix culture is hiring only those employees who best fit the Netflix vision. ”(A) great workplace is stunning colleagues. Great workplace is not espresso, lush benefits…we do some of these things, but only if they are efficient at attracting and retaining stunning colleagues. Like every company, we try to hire well. Unlike many companies, we practice: Adequate performance gets a generous severance package” (Hastings, 2009) Hastings goes on to explain that Netflix hires, develops and cuts employees with the goal of having “stars” in every position in the company. HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 12 This aggressive approach to human resources serves two purposes. First, it lets new and prospective employees know the kind of organization they are coming into right from the start. Netflix asks a great deal of its employees in terms of creativity and innovative thinking. As Robbins, et al. (2012) explain, the process of socializing and acclimating new employees needs to begin early and should be reinforced often. The second function of Netflix aggressive approach is to give managers straightforward guidelines of what to look for when promoting and firing employees. Netflix uses the Keeper Test, which asks: “Which of my people, if they told me they were leaving for a similar job at a peer company, would I fight hard to keep at Netflix?” (Hastings, 2009) With this question to guide them, managers at Netflix know what qualities the organization is looking for when considering hiring, retaining, or dismissing employees. The company readily admits that their high performance culture is not right for everyone, and they are very selective when it comes to their employees. Organizing Netflix focuses on outcomes rather than processes. This is important in a rapidly changing digital environment where processes can become obsolete even before they are formalized. This focus on outcomes in an organic environment means Netflix gives its employees a great deal of empowerment and latitude in their day-to-day decision making. Hastings belief is that as the formalization of an organization increases, the company is unable to adapt quickly to market shifts because they are used to doing things one way. His solution to this problem is to focus on employee performance instead of procedures. By doing this, Netflix HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 13 is still able to grow, but still operate with the flexibility of a smaller firm. Figure 4, Employee Performance vs. Business Complexity (Hastings, 2009) illustrates this concept. Figure 4, Employee Performance vs. Business Complexity (Hastings, 2009) Netflix describes its organizational structure as a highly aligned, loosely coupled group of teams. Goals are clearly and broadly understood by team members. Each team focuses on strategy rather than process, and there is a minimum of meetings between teams. In this way, Netflix hopes to capitalize on the talented people that they hire by providing them with an environment most conducive to innovation and managing change. The Future Netflix turnaround can be attributed largely to its organizational structure, designed to compete in an uncertain environment of rapid change and innovation. After bottoming out at $53.80, Netflix stock has made a dramatic recovery. Figure 5, Netflix Stock Price, Sept 15, 2012 - Nov. 1, 2013 (Yahoo Finance, 2013) shows Netflix 444% growth in the last 14 months. HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 14 10/21/13 $354.99 09/25/12 $53.80 Figure 5, Netflix Stock Price, Sept 15, 2012 - Nov. 1, 2013 (Yahoo Finance, 2013) Netflix operates in an environment of constant change. The company has recently started producing exclusive original content. Their series House of Cards is the first non-broadcast television program to win an Emmy award. Netflix subscriber base has grown from 22 million to over 31.3 million U.S. subscribers since October 2011 (Yahoo Finance, 2013). The company has its sights set on eventually reaching 90 million U.S. subscribers. A company with this level of growth and volatility in their market must be efficient, flexible, and durable in order to operate in a creative digital marketplace. Netflix vision of the future drives its people to achieve results that defy most analysts’ predictions. Empowering employees and providing them with the right environment allows Netflix to remain an innovative leader in the online streaming entertainment industry. HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 15 References Bower, J. L., & Christensen, C. M. (1995, Jan/Feb). Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. Harvard Business Review, 73(1), pp. 43-53. Retrieved October 2, 2013, from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=6&sid=1a0dbaa7-336d-4a8b9cf5-a83727fd4318%40sessionmgr110&hid=120 Braun, M., & Latham, S. (2012). Pulling Off the Comeback: Shrink, Expand, Neither, Both? The Journal of Business Strategy, 33(3), 13-21. Retrieved October 4, 2013, from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1012564580?accountid=12064 Buschman Vasel, K. (2013, April 23). After a Solid Comeback, What's Next for Netflix? FoxBusiness.com. Retrieved October 3, 2013, from http://www.foxbusiness.com/personal-finance/2013/04/23/after-solid-comeback-whatnext-for-netflix/ Gilbert, J. (2011, October 12). Qwikster Goes Quickly: A Look Back at a Netflix Mistake. Huffington Post. Retrieved October 2, 2013, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/10/10/qwikster-netflix-mistake_n_1003367.html Google Finance. (2013, n.d.). Retrieved November 1, 2013, from https://www.google.ca/finance?cid=672501 Hartung, A. (2013, January 29). Netflix: The Turnaround Story of 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2013, from Forbes.com: http://www.forbes.com/sites/adamhartung/2013/01/29/netflixthe-turnaround-story-of-2012/ Hastings, R. (2009). Netflix Culture: Freedom & Responsibility. Retrieved October 2, 2013, from http://www.slideshare.net/reed2001/culture-1798664 Hastings, R. (2011, September 18). Netflix US & Canada Blog. Retrieved October 4, 2013, from http://blog.netflix.com/2011/09/explanation-and-some-reflections.html Kell, E. (n.d.). Learning To Say I'm Sorry. Baylor Business Review. Retrieved October 3, 2013, from http://bbr.baylor.edu/sorry/ HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 16 Kerin, R. A., Hartley, S. W., Rudelius, W., Clements, C., & Skolnick, H. (2012). The Core (3rd Canadian Edition). McGraw-Hill Ryerson. Loftus, T. (2011, September 19). Netflix Customers: Sorry Doesn't Cut It, Pal. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 6, 2013, from http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2011/09/19/netflixcustomers-sorry-doesnt-cut-it-pal/ Manning, T. (2012). Managing Change in Hard Times. Industrial and Commercial Training, 44(5), 259-267. Retrieved October 9, 2013 McMillan, G. (2011, October 25). Financial Analysts Declare Netflix Broken and Suffering Nuclear Winter. Time Tech. Retrieved October 3, 2013, from http://techland.time.com/2011/10/25/financial-analysts-declare-netflix-broken-andsuffering-nuclear-winter/ Miller, S. (1997). Implementing Strategic Decisions. Organization Studies, 18(4), 577-596. Retrieved October 3, 2013, from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=6&sid=13a29cff-777d-4958855a-19fd4d95fcd1%40sessionmgr113&hid=120 Pearce, J. A., & Robbins, K. D. (2008). Strategic Transformation as the Essential Last Step in the Process of Business Turnaround. Business Horizons, 51(2), 121-130. Retrieved October 3, 2013, from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=4&sid=efdbeef4-ea51-4c5ea9abf61224dbc1da%40sessionmgr113&hid=120&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY2 9wZT1zaXRl#db=bth&AN=29373960 Richardson, A. (2011, September 20). Netflix Bold Disruptive Innovation. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved October 2, 2013, from http://blogs.hbr.org/2011/09/netflix-bolddisruptive-innovation/ Robbins, S. P., Coulter, M., Leach, E., & Kilfoil, M. (2012). Management (10th ed.). Toronto: Pearson. HOW NETFLIX SURVIVED DISASTER 17 Stewart, J. B. (2013, April 26). Netflix Looks Back on its Near Death Spiral. The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2013, from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/27/business/netflix-looks-back-on-its-near-deathspiral.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1 Westley, F., & Mintzberg, H. (1989). Visionary Leadership and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 10, 17-32. Retrieved October 5, 2013, from http://library.lethbridgecollege.ab.ca:2052/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=538548c94522-4287-9d5f-0698df26ee0a%40sessionmgr114&vid=1&hid=103 Wikipedia. (2013, October 13). Retrieved November 1, 2013, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Netflix#History Yahoo Finance. (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2013, from http://ca.finance.yahoo.com/echarts?s=NFLX#symbol=nflx;range=20110707,20121031;c ompare=;indicator=volume;charttype=area;crosshair=on;ohlcvalues=1;logscale=off;sourc e=undefined;