annual report 2014 - Office of the Public Advocate

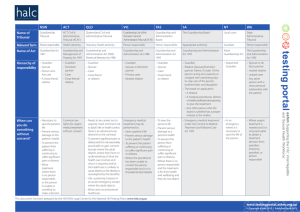

advertisement