Office of the Public Advocate Systems Advocacy

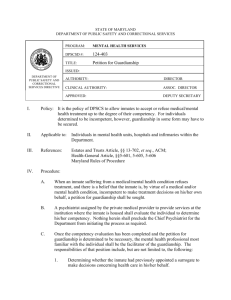

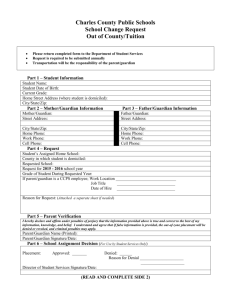

advertisement