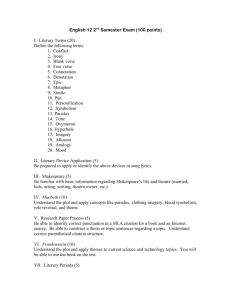

An Outline Introduction to Western Literature

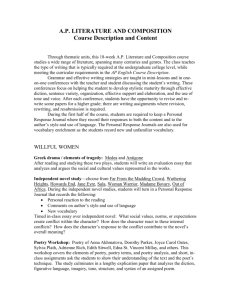

advertisement