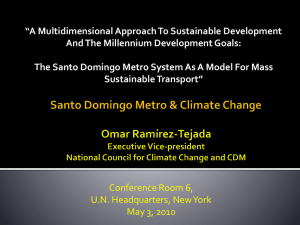

Global Automobile Industry: Changing with Times

advertisement