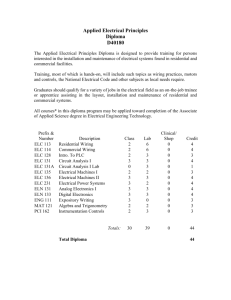

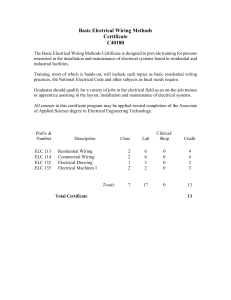

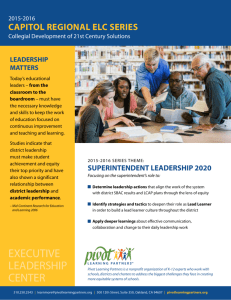

Putting the Pieces Together

advertisement