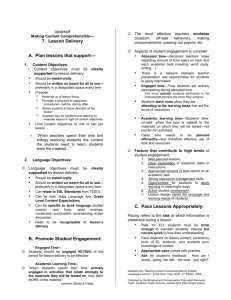

creating an engaged workforce

advertisement