The Use of the OT Law in the Christian Life: A

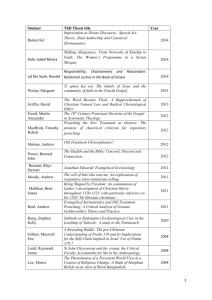

advertisement

E/17/1 (1999): 1-18

EVANGELICAL JOURNAL

issn 0741-1758

The Use of the OT Law in the Christian Life:

A Theocentric Approach

Published semi-annually by

David A. Dorsey

Evangelical School of Theology

121 South College Street

Myerstown, Pennsylvania 17067, U.S.A.

Editor,.H. Douglas Buckwalter

Contributing Editors:

David A. Dorsey

Terry M. Heisey

Robert G. Hower

Leon 0. Hynson

Kirby N. Keller

Kenneth H. Miller

John E. Moyer

William S. Sailer

James L. Schwenk

John V. Tomfelt

Jan1es D. Yoder

Evangelical Journal purposes to provide a forum for scholarly theological

expression consistent with the Wesleyan-Arminian tradition of Evangelical

Protestantism. The scope of the Journal includes investigations in the fields of

biblical, exegetical, historical, systematic, and pastoral theology. Suitable

contributions from the wider evangelical community will be considered for

publication. Views expressed by the contributors are their own, and are not

necessarily endorsed by Evangelical School of Theology or its faculty.

Manuscripts, books for review, and other communications should be addressed to

the Editor. For matters of style, abbreviations, and transliterations, contributors

are requested to consult The Journal ofBiblical Literature 95 (1976): 33-46.

Evangelical Journal is indexed in Religious and Theological Abstracts, New

Testament Abstracts, Old Testament Abstracts, and Religious Index One:

Periodicals. Book reviews are indexed in Index to Book Reviews in Religion.

Subscriptions are $10.00 (foreign $11.00) per year.

Spring 1999

All rights resetved.

One of the most difficult portions of the Bible to utilize in Christian teaching and

preaching is the corpus of Mosaic laws. For many, these laws are confusing,

complicated, boring, strict, and irrelevant to the Christian life-apart from the Ten

Commandments. Yet Paul asserts in 2 Timothy 3: 16 that every part of the (Old

Testanlent) Scripture-including, presumably, each of the 613 laws 1-is of great

value to the New Testament believer. The purpose of this paper is to suggest a

simple hermeneutical and applicational approach by which Christians might more

satisfactorily utilize any of the Mosaic laws, whether moral, civil, or ceremonial.

To do this, we must address two issues: (1) the nature and extent of the law's

applicability to the Christian; and (2) a methodology by which we might properly

apply the laws in our New Testament circumstances.

I. The Law's Applicability to the Christian

The issue of the law's applicability has troubled the Church throughout its history,

and as Cranfield observes, "muddled thinking and unexamined assumptions"

continue to plague modern approaches to the law. 2 Many writers, for instance,

David A. Dorsey, Ph.D. (Dropsie University), is Professor ofOld Testament at Evangelical

School of Theology in Myerstown, Pennsylvania.

1

The number 613 represents the traditional Jewish enumeration and is used here for

convenience. Rabbi Simlai stated, "613 commandments were revealed to Moses at Sinai,

365 being prohibitions equal in number to the solar days [of the year], and 248 being

commands corresponding in number to the parts of the human body" (b. Mak. 23b). Early

tannaitic references to the number 613 include those of Simeon ben Eleazar (Mek. Yitro,

Ba/Jades, 5 [only in edition by I. H. Weiss (1865)], 74 [75a]), Simeon ben Azzai (Sipre

Deut. 76), and' Eleazar ben Yose the Galilean (Midr. ha-Gadolto Gen. 15:1). The number

appears to have been based upon even earlier tradition (cf Tan!Juma, Buber edition, Deut.

17;Exod. Rab. 33:7;Num. Rab. 13:15-16; 18:21; b. Yebam. 47b), and was adopted by the

school of Rabbi Akiva. For a history of the developing Talmudic and rabbinic systems of

enumeration and codification of the laws of Moses, including atl actual list of the 365

prohibitions, and bibliography, see A. H. Rabinowitz, "Commandments, The 613," in

Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 5, pp. 760-783; cf. also John Owen, An Exposition of the

Epistle to the Hebrews, vol. 2 (ed. W. H. Goold; Edinburgh, 1862), pp. 480-499.

2C. E. B. Cranfield, "St. Paul and the Law," SJT 17 (1964): 43.

Evangelical Journal

2

assert that the Ten Commandments represent God's eternal, unchanging will for

all people, but then hedge on the fourth commandment, proposing that it be

modified. 3 The condemnation of homosexuality in Leviticus 20: 13 is usually seen

as normative for our culture, but other laws in that same chapter, including the

prohibition against eating "unclean" animals and the death penalty for the one

who curses his parents, are generally considered "time-bound," applicable only in

ancient Israel. The command in Leviticus 19:18 ("Love your neighbor as yourself') is seen as binding upon the Christian, while the very next stipulation, which

forbids the wearing of cloth woven from two kinds of material, is deemed

inapplicable today.

Part of the problem is that the New Testament itself seems ambivalent on the

subject. On the one hand, Paul insists that believers are "not under the law, but

under grace" (Rom. 6:14); that they have been "released from the law" (Rom. 7:6);

and that Christ has "abolished the law with its commandments and regulations"

(Eph. 2: 15). Paul, on the other hand, considers the law "good" (Rom. 7:12-13)

and "spiritual" (Rom. 7:14) and maintains that it was written "for us" (1 Cor. 9:810). He denies that his emphasis on faith nullifies the law; he exclaims, "Not at

all! Rather. we establish the law!" (Rom. 3:31). Moreover, New Testament writers frequently appeal to various Old Testament laws to define normative Christian

behavior (cf. 1 Cor. 9:8ff.; l Tim. 5:18; Eph. 6:1-3; 1 Pet. 1:15-16, etc.). 4

Christian theologians have been unable to reach a consensus on the issue of

the law's applicability, and a wide variety of mutually exclusive solutions have

been proposed over the centuries. Perhaps the most negative is that of Marci on,

who holds that the Old Testament laws are morally and ethically objectionable,

and unworthv of Christians. 5 Less negative is the view of classic dispensationalism, which. relegates the laws to the "dispensation oflaw," arguing that, while

the laws were good and proper in the Mosaic economy, they are not binding upon

God's people in this present "dispensation of grace." Christ has abrogated the

entire corpus-including the Ten Commandments, with the result that Christians

are no longer under obligation to any part of the law of Moses, only to the law of

Christ. 6 Lutheran theologians. emphasizing the law/grace dichotomy, arrive at a

3

For example, see Jolm Calvin, Institutes, 2. 11.4.

For a helpful recent study of Paul's understanding of the law, see Frank Thielman,

Paul and the Law: A Contextual Approach (Downers Grove, 1994 ).

5Three indispensable works on Marcion are: Adolf von Harnack, Marcion: Das

Evangelium vomfremden Gott, 2nu ed. (1924 ); E. C. Black.man, Marci on and His Influence

(London, 1948); John Knox, Marcion and the New Testament (Chicago, 1942).

6

Lewis Sperry Chafer, Major Bible Themes (Chicago, 1944 ), p. 97; Charles C. Ryrie,

·'111e End of the Law," BS 124 (l 967): 239-47. R1rie admits that the New Testament

enjoins Christians to observe some conunandments that were originally part of the Mosaic

la~v. But this is not to sav, he maintains, that we are obliged to obey some of the Old

Testament laws; rather, w~ are obliged to obey only the law of Christ, which is comprised

of many new commands, and also some old ones that were previously found in the Mosaic

4

The Use (~f rhe Old Testament Law in the Christian L(fe

3

similar conclusion. 7

Reformed theologians, on the other hand. see more continuity bet"'cen the

testaments and a greater Christian responsibility to the law. CoYenant theologians

maintain that the Church is the continuation of Old Testament Israel. Accordingly, Israers laws are our laws. and Christians should a priori be obligated to

all the laws. Many of Isracl 's laws, however. are no longer applicable because of

the new circumstances created by Christ's coming. Reformed scholars propose

that the law comprises three categories: moral, ceremonial, and civil. The civil

laws are no longer operative because they governed a theocratic state which God

has discontinued. Likewise the ceremonial laws arc now obsolete: they functioned

to point symbolically to the coming Christ, and their purpose has been fulfilled

(Acts 15: Rom. 6:14-15; 7:4fT.; Gal. 1:6ff.: 2:14,19: 4:5: 5:18; Heb. 9:10, etc.).

What remains are God's timeless moral laws, such as the Decalogue and the

injunctions to love God and one's neighbor. These are nonnative for all of God's

people at all times. 8

Seventh-Day Adventists, proceeding from a covenant perspective, protest that

it is inconsistent to accept the Ten Commandments as God"s eternal will for all

times and then reject or modify the fourth commandment, the Sabbath law. 9 In

addition, Adventists hold that the dietary laws also remain nonnative for

Christians. 10

•

Christian Reconstructionism (or ·'Theonomy") argues for the normativity not

only of the ''moral" laws but also of the civil regulations. Advocates of this view

code. Ryrie states: "As a part of t11e Mosaic law they are completely and forever done

away. As part of the law of Christ they are binding on the believer today'· (p. 246 ). For

a helpful recent presentation of a dispensational approach to the law, sec Wayne G.

Strickland, "The Inauguration of the Law of Christ with the Gospel of Christ: A

Dispensational View," in W.A. Vangemeren et al. (eds.), The Law. the Gospel. a11d The

Modem Chris1ia11: Five Views (Grand Rapids, 1993), pp. 229-79.

7

For an excellent recent defonse of the Lutheran approach, see Douglas J. Moo, "The

Law of Christ as the Fulfillment of the Law of Moses: A Modified Lutheran View," in

W.A. Vangemeren er al. (eds.), The La11', the Gospel. and the Modem Christian (Grand

Rapids, 1993), pp. 319-76.

8

See standard Refonned Systematic Theologies, such as Charles Hodge, .~vstematic

Theology, vol. 3 (New York, 1877), pp. 267tL Louis BerkhoC Systematic Theology, 4<h

ed. (Grand Rapids, 1941 ); see also Carl F. H. Henry. Christia11 Personal Ethics (Grand

Rapids, 1957), pp. 269ff; John Murra~-, Pn"i1ciples ofConduct (Grand Rapids, 1957), pp.

149ff For a recent defense of th.is view, see Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., Toward Old Testament

Ethics (Grand Rapids, 1983), esp. pp. 307-14.

9

Seventh-DayAdve11tistsA11s-.1•erQ11estio11s 011 Doctrine (Washington, D.C ., 1957), pp.

121-34, 149-76.

10

Thid., pp. 622-24. It should be noted that t11e reason given for observance of these

dietary laws is for health, rather than theological, consideration: ·'It is trne we refrain from

eating certain articles ... but nor because the [ceremonial] law of Moses has any binding

claims upon us'' (p. 623).

4

Evangelical Journal

maintain that their Reformed brothers have erred in discarding the judicial laws:

that while the "ceremonial" laws were fulfilled in Christ, God's civil laws were

not. 11 These civil laws are intended for all governments at all times and should be

instituted and enforced by civil magistrates of every land, including, for example,

capital punishment for blasphemy, apostasy, witchcraft, homosexuality, and

sabbath-breaking. 12

The World-Wide Church of God until recently advocated an even higher

degree of continuity. Armstrong argued that only a few of the laws, such as the

sacrificial regulations, are no longer valid because they were fulfilled in Christ.

The great majority of laws still apply to spiritual Israel, including Sabbath

observance, the keeping of all Jewish feasts and holy days, and observance of all

the dietary and other ceremonial laws. 13

Both the continuity and discontinuity approaches undeniably have strengths.

Certaiuly both can claim support from the New Testament, and both exhibit a

certain internal logic. The continuity approaches correctly perceive the great value

of the law for the Christian, in agreement with Paul. Dispensationalists,

moreover, rightly call attention to the great break between Israel's covenant

responsibilities and the church's, again in agreement with Paul. On the other

hand, neither approach is entirely satisfying. Dispensationalism fails to explain

satisfactorily why a number oflaws (such as the Ten Commandments [or at least

nine of them], the law about holiness, etc.) are treated as normative in the New

Testament. The covenant approach has not provided a convincing rationale for

its tripartite scheme. Particularly troubling to that position is the status of the

fourth commandment (the sabbath law).

I would like to present in this paper a compromise view, one that seeks to

retain the strengths ofboth continuity and discontinuity perspectives. It will be my

proposal that in a strictly legal sense none of the 613 stipulations of the Sinaitic

covenant is binding upon New Testament Christians, including the so-called

moral laws (this in agreement with dispensationalists); at the same time in a

revelatory and pedagogical sense all 613 laws are profoundly binding upon us as

our laws, including all the ceremonial and civil laws. In this latter sense I am in

11 R. J. Rushdoony, The Institutes ofBiblical Law (Phillipsburg, N.J., 1973); Greg L.

Bahnsen, Theonomy in Christian Ethics (Nutley, N.J., 1977); Gary North, "Common Grace,

Eschatology, and Biblical Law," Journal ofChristian Reconstrnction 3 (1976-77): 13-47;

~ee also the reviews in WTJ 38 (1976): 195-217; 41 (1978): 172-89.

12Bahnsen, Theonomy, pp. 207-16,427,439,445,466-67; see also idem., "The Theonomic Reformed Approach to Law and Gospel," in W.A. Vangemeren, et al. (eds.), The

Law, the Gospel, and the Modem Christian (Grand Rapids, 1993), pp. 93-143.

13Herbert W. Armstrong, Which Day is the Christian Sabbath? (Pasadena, 1962);

idem., "Is All Animal Flesh Good Food?" (Ambassador College reprint, 1958); Joseph

Hopkins, The Armstrong Empire: A Look at the World-Wide Church of God (Grand

Rapids, 1974), pp. 135-51, esp. bibliography.

The Use of the Old Testament Law in the Christian Life

5

agreement with reformed theology's high valuation of the relevance of the law for

the Church, except that I would extend this relevance to encompass not just the

Ten Commandments but to all the civil and ceremonial laws as well.

J. The Legal Discontinuity ofthe Law

The New Testament certainly teaches that Christians are no longer legally bound

to at least the vast majority of Old Testament laws. This is clear from the decision

recorded in Acts 15, and from many statements made by Paul and the author of

Hebrews. The New Testament discourages Christians from being circumcised or

following the laws involving Tabernacle worship, the Levitical priesthood, the

sacrifices, cultic purity, and cultic holiness-in other words, nearly all the laws of

the corpus. Certainly the overall impression in the New Testament regarding the

law is its discontinuity.

From a genre-critical perspective the legal inapplicability of the entire Mosaic

corpus would seem logical. The 613 laws functioned as stipulations of a suzerainty-vassal treaty between Yahweh and Israel. Israel violated and, in fact, repudiated this treaty (cf. Jer. 11: 10; 22:9; 31:32; Ezek. 44:7); God consequently abrogated it and established a new treaty with a reconstituted covenant people (1 Cor.

11:25; 2 Cor. 3:6; Heb. 8:6-13; cf. Jer. 31:31-34). When a new treaty or contract

replaces an older one (as, for example, in modern labor contracts), the terms of the

older contract no longer binding upon the parties involved. Granted, parties might

be interested in the terms of an earlier contract for various reasons. But legally it

is the terms of the new contract, not the old, which are binding. The New

Testament portrays Christ's new covenant as replacing or superseding the Mosaic

covenant. This new covenant is called "better" (Heb. 7:22) and "superior" (Heb.

8:6). It involves a "new order" (Heb. 9: 10) and a new body of governing laws and

principles (such as regulations concerning the Lord's supper and baptism;

selection of elders; living under pagan magistrates and laws; and regulations

governing the use of spiritual gifts within the Church). The Mosaic covenant is

called the "old" or"first" covenant (2 Cor. 3:14; Heb. 8:6,7,13; 9:15, 18). And the

writer of Hebrews declares this old covenant and its stipulations to be "obsolete"

(pepalaiacen, Heb. 8:13;palaioumenon, 9:10).

It seems obvious from a consideration of the laws themselves that the Mosaic

corpus of regulations was never intended to govern the Church directly. The corpus is designed to govern a specific nation, located in a specific place, in a specific

time, with a specific cultic organization and a specific political configuration. By

its very nature the corpus, as a corpus, could never have been intended to function

as the normative body oflaws governing the Christian church; its constituent laws

are almost entirely inapplicable to and unfulfillable by Christians. Consider the

following points:

First, the corpus is designed to regulate the lives of a people living in the distinctive geographical and climatic conditions found in the southern Levant, and

6

Evangelical Journal

the majority of its regulations would be inapplicable, unintelligible, or even nonsensical outside that geographically limited locale. Take, for example, the law in

Exodus 29:22 regulating the use of the "fat tail" ('a/yd) of the ram. This law

assumes the availability of the geographically limited Palestinian "fat-tailed"

sheep (which possesses a unique 10-15 pound fatty tail). The law would make no

sense in the many regions of the world where the Palestinian fat-tailed sheep is

unknown, or where there are no sheep at all.

The corpus is penneated with such geographically restricted regulations, such

as those governing or involving:

(1) the cultivation of the Mediterranean olive tree and the use of its fruit

(Exod. 23:11; 27:20; 29:40; Lev. 2:4; 8:30; 24:2; Num. 28:5; Dent.

24:20, to list only a few);

(2) the production and use of emmer wheat, including plowing (Dent.

22:10), sowing (Exod. 23:10; Lev. 19:19; 25:3:ff.; Dent. 22:9), plucking (Dent. 23:25), harvesting (Exod. 34:22; Dent. 16:9; 23:25);

threshing (Lev. 15:20; 18:27; 25:4), gleaning (Lev. 19:9; Dent.

24: 19), and its various religious uses (Exod. 23: 15; 25:30; 29:32ff.;

34: 18; 40:23; Lev. 2: 1-16; 6:14-23; 7:12-13; 8:26,32; 21:6:ff.; Num.

4:7; 28:5:ff.; Dent. 16:3,8, etc.);

(3) the cultivation of vineyards (Exod. 22:5; 23:11; Lev. 19:10; 25:3-5;

Dent. 20:6);

(4) the use of grapes and wine (Exod. 29:40; Lev. 23:13; Num. 6:3-4;

15:5:ff.; 28:14, etc.);

(5) the production and use of flax (Lev. 13:47-48,52,59; Dent. 22:11)including its products, such as linen (bad; Exod. 28:42; 39:28; Lev.

6: 10 [Heb. 6:31]; 16:4) and "fine linen" (ses; Exod. 25:4; 26:1,3 l:ff.;

27: 16, 18; 28:5:ff., etc.);

(6) the cultivation and use of the pomegranate, the date palm, acacia, almond, cassia, cinnamon, galbanum, frankincense, hyssop, Near

Eastern poplar, bitter herb (Exod. 28:33-34; 39:24:ff., etc.);

(7) the raising, safekeeping, slaughtering, eating, and uses of such

Palestinian-and non-universal-animals as the Near Eastern ox

(Exod. 20:17; 21:28-22:15; 23:12; 34:19; Lev. 3:1; 9:4; 22:23;

27:26; Dent. 5:14; 14:4; 22:10, etc.), the Syrian black goat (Exod.

25:4; 26:7; 36:14; Lev. 1:10; 3:6,12; 4:23:ff.; 5:6; 7:23; 16:1:ff.; 17:3;

Num. 18:15-17; Dent. 14:4, etc.), the donkey (Exod. 23:4,12; Dent.

22:10); the camel (Lev. 11:14; Dent. 14:7), the "turtledove" (tar;

Lev. 1:14; 5:7, 11; 12:6,8; 14:22,30; 15: 14,29), and the "pigeon"

(y6nci, or guzal; Lev. 1:14; 5:7,11; 12:6,8; 14:22,30; Num. 6:10,

etc.);

(8) the eating of dozens of various and sundry animals, listed in Leviticus

The Use of the Old Testament Law in the Christian Life

7

11 and Deuteronomy 14; many of which are found only in the

Levant or in the Mediterranean world-and nearly half of which

have not been identified by modem scholars (such as the dilklpat in

Dent. 14:18);

(9) Also geographically restricted are the many climatically specific regulations, such as those which require particular actions at particular

times of the calendar year; for example, the commandment to begin

harvesting the standing grain seven weeks after Passover, in May/

June (Lev. 23:5-20; Dent. 16:1,9), or the ordinance that a feast be

held in September/October at the end of the harvesting of crops (Lev.

23:33-39; Dent. 16:13-15). (Such regulations would be nonsensical, for example, throughout the southern hemisphere.).

Such a corpus could never have been intended to function as the nonnative body

of laws governing the Christian Church, scattered as it is throughout every clime

of the inhabited earth, from Polynesia and the Amazon jungle to the Russian

tundra.

Second, the corpus was designed to regulate the lives of a people whose cultural milieu was that of the ancient Near East. The stipulations of the corpus involve

or regulate culturally-specific practices, institutions, and customs that would be

unknown or little known outside the ancient Near East. These stipulations would

be inapplicable and in many cases meaningless outside that world. For example,

the instructions irr Deuteronomy 20:10-20 for waging siege warfare against a

walled city, while perfectly meaningful in the cultural context of the ancient Near

Eastern world where cities were walled and siege warfare was practiced, would be

pointless in cultures of the world, where walled, fortified cities are unknown.

Most of the laws of the corpus are culturally restricted, including regulations

governing or involving:

(1) the style of slavery found in the ancient Near East (Exod. 20:8-10, 17;

21:1-11,20-21,26-27,32; 23:12; Lev. 25:6,8-l 7,39-55;Deut. 5:1415,21; 15:12-18; 16:11,14; 23:15-16);

(2) polygamy (Dent. 25:5-10);

(3) the bride price (m6har; Exod. 22: 16-17);

(4) concubinage (Lev. 19:20);

(5) the "kinsman redeemer" (g6 'el; Lev. 25:25-49, etc.);

(6) the giving of gannents in pledge (Exod. 22:26; Dent. 24:6,10-17);

(7) gleaning (Lev. 19:10; Dent. 24:21);

(8) stoning (Dent. 13:10; 17:5; 21:21; 22:21,24, etc.);

(9) swearing oaths by invoking a deity (Lev. 5:4; 19: 12; Num. 30:2;

Dent. 6:13; 10:20, etc.);

( l 0) the style of hereditary kingship practiced in the ancient Near East

8

Evangelical Journal

(Deut. ch. 17);

(11) city gates functioning as courtrooms (Deut. 21:19; 22:24; 25:7, etc.);

(12) stone houses with plastered interior walls (Lev. 14:33-53);

(13) "town squares" adjacent to a city's gate (rehiiJot; Deut. 13:16);

(14) horse-drawn chariots (Deut. 20:1);

(15) forced labor (mas; Deut. 20:11);

(16) the flat roofs of private homes (Deut. 22:8);

(17) tasseled gannents (Num. 15:38-40);

(18) granting special rights to the first-born son (Deut. 21:15-17);

(19) the tribal organization of society (Exod. 28:21; Num. 33:54; Deut.

12:5, 14, etc.);

(20) the blood avenger (Deut. 19:6ff.).

Third, the corpus was designed to regulate the lives of people whose religious

milieu was that of the ancient Near East (particularly Canaan) and would make

little sense outside that world. Consider, for example, the various laws regulating

the construction and use of the priestly ephod (Exod. 25:7; 28:4ff.; Lev. 8:7, etc.).

These ephod laws would be perfectly intelligible and meaningful to people living

in the religious milieu of the Near East, where ephods were apparently wellknown. But for people living outside Israel's religious milieu, who would not even

know what exactly an ephod was, much less its function, these instructions would

be meaningless.

The corpus is filled with laws involving such culturally-restricted cultic/

religious elements, including regulations governing or involving:

(1) the Near-Eastern-style cultic sanctuary (cf. the Tabernacle regulations);

(2) the cultic altar, particularly the homed altar (Exod. 20:24; 21:14;

29:37,44; 30:27; 34:13; Deut. 7:5; 12:3, etc.);

(3) cultic incense (Exod. 30:8-9; Lev. 10: l; 16: 13, etc.);

(4) Levantine-style cultic offerings and sacrificial meals, including the

'Old-offering, the minhd-offering, the hatta't-offering, the 'asiimoffering, and the .Selem-offering (Lev. chs. 1-7 and throughout the

corpus);

(5) religious vows and votive offerings (Lev. 7:16-17; 22:21,27, etc.);

(6) cherubim (Exod. 25:18-19; 26:1,31);

(7) the institution of the Nazarite (Num. ch. 6);

(8) the Near Eastern institution of the prophet (Deut. 18:14-22);

(9) the Near Eastern institution of the cultic priest (Exod. chs. 28-29;

Lev. chs. 1-10, etc.).

Fourth, the corpus lays the detailed groundwork for and regulates the various

The Use of the Old Testament Lmv in the Christian Life

9

affairs of an actual politically- and geographically-defined nation. The corpus

regulates, for example, Israel's national and internal boundaries, its system of

government, its judicial system, and its foreign and domestic policy. Such a

corpus could not have been intended to serve as the body of laws governing the

Church, since the Church is not a politically- and geographically-defined nation

but is composed of pockets ofbelievers living as minorities throughout virtually

all the (pagan) nations of the earth, believers who have been instructed in their

new covenant to comply with the established forms of govern-ment and legal

systems of their respective nations (e.g., Rom. ch. 13).

The corpus is filled with laws in this category, including (to mention only a

few) regulations governing:

(1) the selection and behavior of the nation's king (Deut. 17:14-20);

(2) the preservation and maintenance of the tribal system of internal organization and the tribal divisions of the land of Canaan (Num.

34:13-18, etc.);

(3) the appointment of officials and judges over each of the twelve tribes

(Deut. 16:18-20);

(4) the legal functions of the Levitical priests (Deut. 17:8-13);

(5) the choosing, function, and maintenance of the six cities of refuge

(Deut. 19:1-13);

(6) the nation's ancient-Near-Eastern-style judicial system (Exod. chs.

21-23);

(7) the rather stern foreign policies involving the countries of Ammon

and Moab (Deut. 23:3-6);

(8) the more amicable foreign policies toward the Edomites and

Egyptians (Deut. 23 :7-8);

(9) the herem procedures to be followed against the Amalekites (Deut.

25:17-19) and Canaanites (Exod. 23:23-33, etc.);

(10) the practice of near-Eastern-style chariot and siege warfare (Deut.

ch. 20, etc.);

(11) the treatment of women captured in warfare (Deut. 21: 10-14).

Fifth, the corpus is designed to establish and maintain a cu/tic regime which

was restricted to ancient Israel and has been discontinued in the Church (cf. Heb.

chs. 7-10). Hundreds oflaws in the corpus regulate the Tabernacle and its service

(Exod. chs. 2-40, etc.), the Levitical/Aaronic priesthood (Exod. chs. 28-30; Lev.

chs. 1-10, etc.), and the sacrificial system (Lev. chs. 1-7; 16-17; 22:17-30, etc.);

and many other laws require these three interrelated cultic institutions. For

example, the prescribed procedures for observance of Sabbath, New Moon,

Passover, Feast of Weeks, Feast of Tabernacles, and Day of Atonement all involve

animal sacrifices (e.g., Lev. 23: 12,18,25; Num. 28:9-29:40, etc.),Leviticalpriests

Evangelical Journal

10

(Lev. 23:11,20, etc.), and the Tabernacle (Deut. 16:5-6,11,15). In light of the fact

that nearly all of the Mosaic laws assume and in fact require these discontinued

cultic institutions, it seems unlikely that the corpus could be intended as the body

of laws governing the Church.

In sum, virtually all the regulations of the corpus-certainly ninety-five

percent-are culturally restricted, geographically limited, and cultically and

politically specific, and as a result are inapplicable to, and in fact unfulfillable by,

Christians living throughout the world today. This fact alone should show that the

corpus could never have been intended as the direct marching orders of the

Church.

Covenant theologians could respond that the above considerations support

only the inapplicability of the time-bound laws of the corpus, but that there are

within the corpus a handful of timeless moral laws (such as the Decalogue) which

apply to all of God's people at all times, laws which are repeated in the New

Testament and remain normative for the Church. The proposition that one

particular category of laws has been granted special legal status for the Church,

is, of course, one way to account for the biblical data. Three considerations,

however, mitigate against this position.

First, to repeat a tired cliche, the scheme of a tripartite division is unknown

both in the Bible and in early rabbinic literature. Its formulation appears rather

to be traceable to modern Christian theology. 14 The New Testament speaks of

obligation to the Law in quite monolithic terms. Legal obligation to only one

special set oflaws is nowhere suggested. Jesus, for example, taught that "the one

who breaks the least of these commandments . . . will be called least in the

kingdom of heaven" (Matt. 5:19).

Second, the categorizing of certain laws as "moral" is methodologically

questionable. For which of the 613 laws is not "moral"? 15 The Sabbath law, the

parapet law, the prohibition against muzzling the treading ox, indeed, all the socalled "ceremonial" and "civic" laws embody or flesh out eternal moral and ethical

principles-just as do the "moral" laws. Conversely, a number of the laws categorized as "moral" contain time-bound and culture-bound elements. The fourth

commandment (Deut. 5: 12-15), for example, involves ancient Near-Eastern-style

slavery, geographically limited animals (oxen and donkeys), and an ancient

Increasingly the validity of this tripartite division of the Law is being challenged.

Ryrie, "End of the Law," pp. 239-44, argues that the division is the product of Christian

Theology and has no roots in the Jewish concept of the Law. G. J. Wenham, The Book of

Leviticus, NICOT (Grand Rapids, 1979), p. 32, calls the three-fold division "arbitrary and

artificial," one not attested in the New Testament. For a list of other commentators

(including H. A. W. Meyer, John Knox, G. B. Stevens, F. Godet, and W. R. Nicoll) who

have challenged this popular scheme, see Kaiser, "Weightier and Lighter Matters," pp.

179-180, n. 15.

15

So Wenham, Leviticus, pp. 32,34ff. and others.

14

The Use of the Old Testament Law in the Christian Life

11

fortification system featuring city gates. The mention of the ger ("alien") in this

commandment (v. 14) implies the existence of the geographically and politically

defined nation of Israel. The motive clause in verse 15, with its reference to

Israel's Exodus from Egypt, clearly excludes Gentile Christians. Likewise the

motive clause in the fifth commandment requiring the honoring of one's parents

(Deut. 5: 16) assumes the existence of the theocratic state of Israel in the land of

Canaan ("that it may go well with you in the land the Lord your God is giving

you").

One wonders, in fact, if most of the so-called "moral laws" achieved their

special status among theologians simply because of literary happenstance: they

are the stipulations in the corpus which happen not to include a time-bound word,

phrase, or clause in their verbal expression. Would the fifth commandment have

been selected if the purpose clause at its end had been slightly longer: "Honor

your father and mother that you may live long in the land of Canaan which I am

giving to your twelve tribes" (which is certainly the intent of the command)? Or

the sixth commandment, if it had been more fully stated: "You shall not murder,

and he who does shall be tried before Levitical judges in one of the six cities of

refuge located on the west or east sides of the Jordan river?"

Third, the positing of a special category to save the "moral" laws for the

Church may be methodologically unnecessary. A more logical approach to the

law's applicability retains for Christians the very heart of all the "moral" laws, as

well as the underlying moral truths and principles, indeed the very spirit, of every

one of the 613 laws.

2. The Continuity of the Law in a Revelatory and Didactic Sense

Having argued that the Mosaic law in its entirety be removed from the backs of

Christians in one sense, I would propose that the entire corpus be placed back into

their hands in another sense, not just the "moral" laws, but all 613 moral, ceremonial, and civil laws. For if, on the one hand, the evidence strongly suggests that

the corpus is not legally binding upon the Christian, there is equally strong

evidence in the New Testament that all 613 laws are profoundly binding upon the

Christian in a revelatory and pedagogical sense.

Paul's implies that all the laws are applicable to Christians in this latter sense

in his well-known statement in2 Timothy 3:16: "All scripture is inspired by God

and is profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in

righteousness, that the person of God may be complete, equipped for every good

work." This assertion, referring as it does to the Old Testament, presumably

applies to all the Old Testament Scriptures, including each of the 613 laws. This

implies that each of the laws is inspired by God, and that each is valuable for

determining theological truths, correcting misconceptions, exposing and rectifying

wrong.be]lavior, and training and equipping the Christian in righteousness.

When Paul addresses himself specifically to the question of the revelational

12

Evangelical Journal

and didactic value (and not the legal applicability) of the Law, he expresses

nothing but the highest regard for it. He considers the laws to be God's laws, and

he "delights" in them (Rom. 7:22,25; 8:7; 1 Cor. 7:19). The laws are "good"

(Rom. 7:12-13,16; 1 Tim.1:8), "holyandrighteous"(Rom. 7:12),and"spiritual"

(Rom. 7: 14 ). Paul considers the laws valuable in the identification and conviction

of sin in one's life (Rom. 3:20; 7:7ff.). He teaches, as did Jesus, that each individual law of the Mosaic corpus (and not just laws of a certain category) fleshes

out the one overarching law, "Love your neighbor as yourself' (Rom. 13:9; Gal.

5:14). He implies that each law was given and recorded "for us" (1 Cor. 9:8-10).

Central to my understanding of the Old Testament law's applicability to

Christians is the fact that God issued these laws. They reflect the very heart and

mind of the God we seek to know and serve. Accordingly, the laws comprise a

treasure of insights and information about God and his ways and therefore will be

binding upon Christians in precisely the same sense as are all other portions of the

Old Testament. While the Mosaic stipulations are not our stipulations, they were

issued by our God, who does not change. If the corpus was tailor-made for another

people in another situation, it was tailored by the One we seek to obey. It is here

that I find the point of profound applicability for the Christian. A law reflects the

mind of the law-giver. Accordingly, each law issued by God to ancient Israel (like

each declaration by God through the prophets) reflects God's mind and ways, and

is therefore a valuable source of theology; the theological insights we gain from

a particular law, whether that law be "moral," "ceremonial," or ''judicial," will not

only enhance our understanding of God but will also have important practical

implications for our own lives, if we are patterning our lives after our heavenly

Father and modifying our behavior in response to our knowledge of him and his

ways (Paul argues along these very lines in 1 Cor. 9:9-10). In this revelatory and

pedagogical sense, every one of the 613 laws of Moses is binding upon Christians.

II. Methodology in Applying the Law

We have addressed the issue of the law's applicability. It now remains for us to

consider the issue of methodology in applying the law. In this last section of my

paper my purpose is to propose a practical methodology for utilizing the Old

Testament laws in our modern Christian lives, and to illustrate this approach with

examples from each of the three categories of laws.

If the laws do not legally bind us (so that we are looking over the shoulder of

the Jew, so to speak, when we view them), how can we properly apply them to our

own lives? I propose that we use the same basic applicational procedure that we

do for any other portion of the Old Testament. I would suggest that we follow a

simple three-step, theocentric approach when dealing with any of the 613 laws (or

any other passage of the Old Testament), what I call the "CIA" approach.

The Use of the Old Testament law in the Christian life

13

1. Clarification ("C"). The first step is to clarify the law's meaning. What

was the original intent, significance, and purpose of the law? What was its point

(every law presumably has a point, a purpose)? What was the law designed to

accomplish? What problem was it attempting to correct? What behavior or

attitude was it attempting to encourage? Why was it issued? Here ancient Near

Eastern comparative material can often be helpful. 16

Take, for example, the law in Deuteronomy 22: 12: "Make tassels on the four

corners of the cloak you :wear." In a study on tassels, Stephen Bertman found that

wearing tassels in the ancient Near East was normally the prerogative of royalty

or people of special status, such as priests. 17 If Bertman is correct, then

presumably the tassels were intended, at least in part, to function as reminders to

the Israelites of their special royal/priestly status before God. The parallel passage in Numbers 15:37-40 supports this. It mentions the (royal) blue thread of the

tassel and speaks of the sacred status of the Israelites. The tassels are to remind

Israel of their (priestly) duty, as God's royal priests, to remember and keep all of

his laws.

2. Insights about God and His Ways ("I"). After clarifying the meaning of

the law, a second step is needed to transform the Old Testament regulation, with

its specificity and particularity, into a more general fonn which can then be

reapplied in our modern lives. Here Goldingay, Kaiser, and others propose that

we must discover the principle, or "middle axiom," underlying the specific Old

Testament law, so that we can apply that underlying principle to our modern

circumstances. 18 Kaiser refers to this process as moving up and down the !adder

of abstraction. He illustrates the process with the law about muzzling tl1e ox in

Deuteronomy 25:4. The "BC [before Christ] specific situation" was "oxen tread

wheat"; the "New Testament specific situation" was that Paul could be paid for

preaching; and the "general principle" is: "giving engenders gentleness and

graciousness in humans." 19 The basis for commonality between the original

regulation and its New Testament application is, according to Kaiser, "Moses'

concern that gentleness and gratitude be developed both in owners of hardworking oxen and in listeners to hard-working preachers." 20

This concept of "principalizing" Old Testament laws may be helpful; but I

16

See, for example, John H. Walton and Victor H. Matthews, The !VP Bible

Background Commentary: Genesis-Deuteronomy (Downers Grove, 1997).

17

Stephen Bertman, "Tasseled Gannents in the Ancient East Mediterranean," BA 24

(1961): 119-28.

18

See, for example, John Goldingay, Models for Interpretation of Scnpture (Grand

Rapids, 1995); idem., Approaches to Old Testament Interpretation (Dov>'ners Grove, 1981 ),

pp. 51-55.

1

9Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., Toward Rediscovering the Old Testament (Grand Rapids,

1987), p. 166.

20

Ibid., p. 164.

14

Evangelical Journal

would suggest that the focus of this second step be sharpened to ascertain,

specifically, the theological significance of the law. What does the law reveal

about God and his ways? What does it reveal about God's mind, personality,

qualities, attitudes, priorities, assumptions, presuppositions, values, concerns,

teaching methodologies, and the kinds of attitudes and moral and ethical standards

he wants to see in those who serve him? I agree wholeheartedly with Vangemeren

when he writes, "the law[s of the Decalogue] reveal ... the character of the

Lawgiver." 21 My only quibble with Vangemeren is that what he says of the Ten

Commandments is also true of all the laws; for surely all the laws issued by God

reveal his character. Granted, all 613 laws were issued by God for another people

who lived at another time under very different circumstances than ours; but all of

these laws come from the same immutable God whom we seek to serve. They

represent a vast reservoir of potentially life-changing insights about him and his

ways.

Take, for example, the tassel law. From this law it is clear that God holds his

people, including both men and women, in very high esteem. Whether rich or

poor, in his eyes they all possess royal status; each is a special person of priestly

status. God, however, is not satisfied simply to know their value himself; this law

suggests that he also wants his people to be aware of their high status in his eyes

(thus the reminders). Moreover, he seems to think that a visual reminder of an

important but easily forgotten spiritual truth can be helpful. These are just some

of the things we learn about God and his ways from this law.

3. Application ("A"). In the approach I am proposing, the practical application of an Old Testament law should spring from the theological insights

derived from that law. As one ponders how to apply a Mosaic law, the question

should be asked: In light of what I learn about God and his ways from this Old

Testament stipulation, what modifications should I make in my own life, in my

own New Testament circumstances? Here I find helpful Knox Chamblin's reminder that in the application process three factors must be considered in distinguishing our New Testament situation from that of the Old Testament: epochal,

cultural, and personal. 22 I must remember that I live within a new covenant (one

without animal sacrifices, Levitical priests, etc.); that I live in a culture very different from the culture of ancient Israel; and that my own personal circumstances

and needs may call for a very personalized application.

Returning to the tassel law, in light of what I learn about God and his ways

from this law I might decide that I need to reassess my own perception of my value

21 Willem A. Vangemeren, "The Law is the Perfection of Righteousness in Jesus

Christ: A Reformed Perspective," in W. A. Vangemeren eta!. (ed.), The Law, the Gospel,

and the Modern Christian (Grand Rapids, 1993), p. 55.

22f<.nox Chamblin, "The Law of Moses and the Law of Christ," in J. S. Feinberg (ed.),

Continuity and Discontinuity: Perspectives on the Relationship between the Old and New

Testaments (Wheaton, 1988), pp. 183-84.

The Use of the Old Testament Law in the Christian Life

15

before God. If that perception is not in line with what I have learned about God's

evaluation of his people from this law, I might decide to place on my desk or wall

a Bible verse that will frequently remind me of my importance to him. I might

also consider making a number of specific modifications in my daily life,

eliminating questionable behaviors that are not in keeping with my high status in

God's eyes.

This approach works equally well with all three "categories" of laws.

Consider, for example, one of the "moral" laws from the Ten Commandments.

The fifth commandment states: "Honor your father and your mother, so that you

may live long in the land the Lord your God is giving you" (Exod. 20: 12).

Although this law was part of a treaty that is no longer legally binding upon me,

I am still responsible for whatever I learn about God and his ways from it.

Regarding the law's point, its purpose appears to be, at least in part, to insure that

aging parents be treated with all due honor and respect. The law, presumably

addressed to adults (cf. Matt. 15:2ff.), eajoins Israelites to treat their parents with

dignity and honor. What does this law reveal about God and his ways? It

certainly shows that he is sensitive to the plight of the elderly, who grow

progressively more vulnerable and less "useful" as they age. The law also reveals

that God wants his people to share that sensitivity, first and foremost by treating

their own aging parents with honor and respect. In light of what I discover about

God's heart and mind from this law, I might be led to a whole variety of

applications involving supporting, respecting, or honoring my own parents or any

other elderly person or group of people. Conversely, an elderly Christian widow

might take heart from the fact that this law suggests that God cares about the

plight of the elderly and that he deems elderly women worthy of honor. In light

of this, the elderly widow might be inspired to make any number of positive

modifications in her daily life to reflect her newly-understood value in God's eyes.

The judicial laws likewise offer a treasure of potentially life-changing insights

about God and his ways. The meaning and theological significance of many of

these laws can best be ascertained by comparison with other law codes from the

ancient Near East. Through such comparisons we, in part, discover God's high

valuation of human life, the importance he places on t11e individual, his high view

of and great sensitivity toward women, slaves, poor, and people of an ethnic

minority, his disapproval of class systems, and his love for justice, equity, and

reason.

Take as an example from the judicial laws Deuteronomy 24: 10-12, which

reads, "When you make a loan of any kind to your neighbor, do not go into his

house to get what he is offering as a pledge. Stay outside and let the man to whom

you are making the loan bring the pledge out to you." The law calls for creditors

and those granting assistance to the poor to exercise great sensitivity for the

feelings of the poor, even in the delivery of the help. Allowing the borrower to "be

in charge" by bringing the piece of collateral out to his creditor serves to preserve

16

Evangelical Journal

some dignity for the borrower, whereas permitting the creditor to enter the

borrower's home to confiscate the collateral would result in a further sense of

humiliation on the part of the borrower. This law offers a fascinating glimpse into

God's remarkable sensitivity for the feelings of poor people who seek assistance;

this insight about God's way of thinking should inform how we in the church offer

assistance to the hungry, how we deliver charity baskets to the poor, etc. In light

of what we learn about God from this law, we should be exceedingly careful that

we do not humiliate those we seek to help. Application of this law could likewise

inform how we teachers deal with struggling students who ask for help (such as

tutoring or extra time on assignments). Clearly we should be very protective of the

feelings of needy students.

Perhaps the most challenging category of law to apply is that of the

ceremonial laws. As with the civil laws, the ceremonial laws can often best be

understood through comparative Near Eastern material. For example, the size of

the tabernacle, five by fifteen yards, takes on new significance when viewed in

light of other ancient Near Eastern temples, some of which were exceedingly

ornate and complex, had many rooms, and measured up to a half mile in length.

God's "Temple," far from competing with the other temples of the ancient world,

was basically a humble goat's hair tent. This suggests a great deal about the

character of God (and incidentally reminds us of Jesus, who "had no beauty or

majesty to attract us to him," Isa. 53:2). God's various instructions about his

tabernacle, its content, and its service reflect a self-assurance that needs no overcompensation, a remarkable humility, a willingness to dwell among his people, a

desire to be known, a willingness to be vulnerable and risk rejection and

humiliation, a delight in simplicity, and a willingness to work with his people

where they are. His requirements for his tabernacle are strikingly simple; they are

not burdensome. The materials he requests for the tabernacle are materials which

are readily available to his people. All this reveals much about God and his ways.

What we learn of him from this Old Testament material will have practical

implications for our own lives.

The sacrificial regulations likewise take on new light when viewed against

pagan sacrificial systems. Sacrifices in the ancient Near East involved many

deities, many types of sacrifices, and many complicated procedures. They functioned to feed and manipulate the deities. In stark contrast, God's sacrificial

requirements were remarkably simple and easy. They remind Israel that God is

spirit and has no bodily needs such as for food. They reveal God's delight in

receiving gifts from his people. They highlight his sensitivity to the poor. They

remind Israel of God's sovereignty over them. At the same time the small number

of required offerings underscores the lightness of his rule over them: Ahab

required 100,000 sheep annually from the small vassal nation of Moab (2 Kings

3:4); in contrast, God requires less than 1200 sheep annually from the entire

nation oflsrael. We learn in these sacrificial regulations that God cares about the

The Use of the Old Testament Law in the Christian Life

17

feelings of his people, that he delights to be a part of their times of celebration, and

that he is humble enough to join them, so to speak, in their special communal

meals. The primary value of these sacrificial regulations was not in how they

foreshadowed Christ's atoning work, but in what they revealed to ancient Israel

and to us about the mind and heart of God. It is these insights about God that are

potentially life-changing for Christians.

To take an example from these ceremonial regulations, consider the

instructions about the table of shewbread (Exod. 25:23-30, etc.). Tables were a

normal part of any pagan temple. The cultic table was used in the feeding of the

deity. Twice daily, meals were served on the table for the deity to consume. The

table was positioned directly in front of the deity so that he could partake of the

food through his eyes. It should also be remembered that according to pagan

mythology, man was created primarily for the purpose of feeding the gods. The

Lord uses the well-known institution of the cultic table to teach his people worlds

about himself, turning the function of the cultic table on its end. In stark contrast

to its pagan counterparts, the table in God's tabernacle is not used by the priests

to serve the daily meals to God; instead, it is used by God to provide daily bread

for his priests. Its placement, positioned not in the Holy of Holies but out where

the priests do their work, underscores its anti-idolatrous message. The instructions

regarding the table reveal that God, rather than needing to be fed by h.is people,

delights to provide them with food. This of course is reminiscent of Jesus' words,

"I have come not to be served, but to serve."

By way of application, having been reminded that God has no bodily needs

and does not need to be fed, a Christian would of course refrain from pagan idol

worship involving feeding the deity as if God needed food. But this is not a likely

temptation for modem Christians. What other application might be possible here?

Since God reveals through these instructions that in some respects he wishes to

serve rather than be served, I might, by way of application as a teacher follow my

heavenly father's example and focus more on serving others rather than on being

served in my profession. I might also need to reexamine my understanding of

God's role in my life. Though God certainly wants me to serve him, perhaps I

also need to balance that concept with the realization, springing from insights

about God from his table of shewbread instructions, that in some respects God is

among his people to serve rather than to be served. Perhaps I need to allow God

. to care for me a bit more, and not be so entirely preoccupied with what I should

be doing for him.

ID. Conclusion

It has been my purpose in this paper to suggest an approach to the Old Testament

law which understands the law as entirely inapplicable to Christians in a legal

18

Evangelical Journal

sense but at the same time profoundly applicable in a revelatory and didactic

sense. I have suggested that all 613 laws, not just the "moral" ones, are binding

upon the Church in this latter sense. This understanding represents a compr~mise

between covenantal and dispensational approaches. In regard to the question of

method, I have proposed a theocentric procedure for applying the laws to our New

Testament circumstances, a methodology which sharpens the focus of the

"principalizing" approach, and which works equally well with any of the laws of

the Mosaic corpus, whether moral, civil, or ceremonial.

The appeal of the approach proposed here, in part, is that it bypasses the

highly disputed question of which laws were "fulfilled in Christ." In a se~s~ it

avoids the thorny debate over continuity/discontinuity and enables the Christian

to appropriate and apply to his or her own life the very heart and spirit of every

one of the laws given by God at Sinai. It provides a way for us to fulfill each of

the 613 laws in a manner that would have delighted Old and New Testament

authors alike, so that in a real sense we can declare with Paul: "Do we then

overthrow the Law? By no means! On the contrary, we establish the Law." In

the Old Testament laws we find, after all, the marching orders for the Church.

El 1111 (1999): 19-31

Broken Families/The Healing Church

Theodore M. Johnson

L Broken Families

The era of the 1940s is a good starting place to see a chain of events that greatly

impacted families in America. World War II took a significant number of men out

of the work force and their replacements were the women left behind. These

women worked in offices, filled empty benches in manufacturing plants, and

worked on the railroads. My own aunt lubricated railway engines in the local

roundhouse.

Many of these women were mothers. When tl1eir husbands went to war, they

functioned as single, working parents, relying on extended family support for

childcare and other needs. When the war was over, many women did not return

to their domestic settings but remained in the workforce.

Our society began a dramatic change. Marriage was no longer the inevitable

next step after high school. Young men and women separated from their families

rather than continuing to live with their parents or using marriage as the primary

means of separation into adulthood.

Divorce was rare. This was partly due to a double standard of permissiveness

for men and subjection for women. Divorce increased as abusive situations,

desertion and other problems became more public, and laws addressed this mistreatment. Divorce increased, as laws became more flexible regarding conditions

for divorce and the legal settlements became more equitable. New laws and regulations made it possible for women to have some :financial and property assets in

the case of divorce, which had not been true previously. Divorce also became

more acceptable in a society focused on individualism and the happiness of the

individual as the highest good.

More women attended business schools and colleges. They entered the

workforce and brought money into the household. More products were available

to make life easier and :fulfillment of dreams more possible. The central role of the

family in our culture gradually eroded.

A number of variables have influenced marriage and family life in the Ur.' 1

Theodore M. Johnson, Ph.D. (Fuller Theological Seminary Graduate School of

Psychology). is a licensed psychologist in private practice and Adjunct Lecturer in

Pastoral Counseling at Evangelical School ofTheology in Myerstown, Pennsylvania. Dr.

Johnson presented this paper at the William S. Sailer Lectureship at Evangelical School

of Theology in January, 1999.