January 10, 2015 Dear Hunters, Recent changes to Wildlife

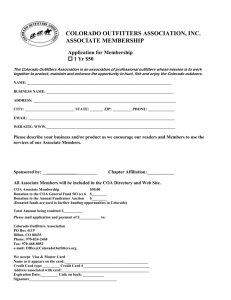

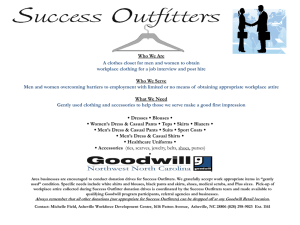

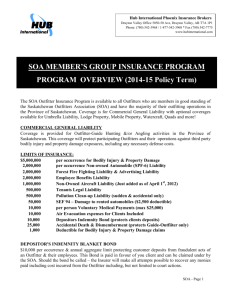

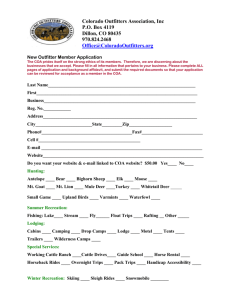

advertisement