C.12 Applications of Optimal Control

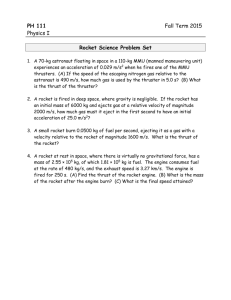

advertisement

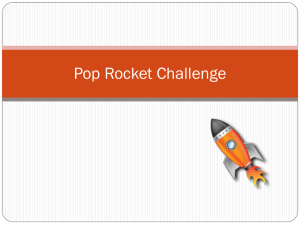

Introduction to Control Theory Including Optimal Control Nguyen Tan Tien - 2002.5 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ C.12 Applications of Optimal Control Problem Minimizing the fuel (cost function) 12.6 Rocket Trajectories The governing equation of rocket motion is J= dv m = m F + Fext dt (8.22) T ∫ β dt (12.41) o subject to the differential constraints where m v F Fext dv1 cβ = cos φ dt m dv 2 cβ = sin φ − g dt m : rocket’s mass : rocket’s velocity : thrust produced by the rocket motor : external force It can be seen that (12.43) and also c β m F = (12.42) (8.23) where c : relative exhaust speed β = −dm / dt : burning rate dx = v1 dt dy = v2 dt (12.44) (12.45) The boundary conditions Let φ be the thrust attitude angle, that is the angle between the rocket axis and the horizontal, as in the Fig. 8.4, then the equations of motion are t = 0 : x = 0, y = 0, v1 = 0, v 2 = 0 t = T : x not specified, y = y , v1 = v , v 2 = 0 Thus we have four state variables, namely x, y , v1 , v 2 and two dv1 cβ = cos φ dt m dv 2 cβ = sin φ − g dt m (8.24) Here v = (v1 , v 2 ) and the external force is the gravity force only Fext = (0,− mg ) . controls β (the rate at which the exhaust gases are emitted) and φ (the thrust attitude angle). In practice we must have bounds on β , that is, 0≤β ≤β (12.46) so that β = 0 corresponds to the rocket motor being shut y down and β = β corresponds to the motor at full power. path of rocket The Hamilton for the system is r v cβ ⎛ cβ ⎞ cos φ + p 4 ⎜ sin φ − g ⎟ m ⎝ m ⎠ (12.47) where p1 , p 2 , p 3 , p 4 are the adjoint variables associated H = β + p1v1 + p 2 v 2 + p 3 φ x Fig. 8.4 Rocket Flight Path (12.47) ⇒ The minimum fuel problem is to choose the controls, β and φ , so as to take the rocket from initial position to a prescribed height, say, y , in such a way as to minimize the fuel used. The fuel consumed is T ∫ β dt o where T is the time at which y is reached. Chapter 12 Applications of Optimal Control with x, y , v1 , v 2 respectively. (8.25) c c ⎛ ⎞ H = p1v1 + p 2 v 2 − p 4 g + β ⎜1 + p 3 cos φ + p 4 sin φ ⎟ m m ⎝ ⎠ c c ⎛ ⎞ If we assuming that ⎜1 + p 3 cos φ + p 4 sin φ ⎟ ≠ 0 , we m m ⎝ ⎠ see that H is linear in the control β , so that β is bang-bang. That is β = 0 or β = β . We must clearly start with β = β so that, with one switch in β , we have 59 Introduction to Control Theory Including Optimal Control Nguyen Tan Tien - 2002.5 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ⎧⎪ β ⎪⎩0 β =⎨ 0 ≤ t < t1 for (12.48) for t1 < t ≤ T Now H must also be maximized with respect to the second control, φ , that is, ∂H / ∂φ = 0 giving − p3 cβ cβ sin φ + p 4 cos φ = 0 m m p& 1 = − ∂H = − p1 = − A ∂v1 ∂H p& 1 = − = − p2 ∂v 2 (12.50) subject to d 2θ 2 +α dθ + ω 2θ = u dt (12.51) Boundary conditions t = 0 : θ = θ 0 , θ& = θ 0′ t = T : θ = 0, θ& = 0 The adjoint variables satisfy the equations ∂H =0 ∂x ∂H p& 1 = − =0 ∂y T 0 dt which yields tan φ = p 4 / p 3 . p& 1 = − ∫ T = 1dt ⇒ p1 = A Constraint on control: | u | ≤ 1 . ⇒ p2 = B Introduce the state variables: x1 = θ , x 2 = θ& . Then (12.51) becomes ⇒ p 3 = C − At ⇒ p 4 = D − Bt x&1 = x 2 x& 2 = a x 2 − ω 2 x1 + u (12.52) As usual, we form the Hamiltonian where, A, B, C, D are constant. Thus H = 1 + p1 y 2 + p 2 (−a x 2 − ω 2 x1 + u ) D − Bt tan φ = C − At where p1 , p 2 are adjoint variables satisfying Since x is not specified at t = T , the transversality condition is p1 (T ) = 0 , that is, A = 0 , and so tan φ = a − bt (12.49) where a = D / C , b = B / C . r v y=y β =0 β =β ∂H = ω 2 p2 ∂x ∂H p& 1 = − = − p1 + ap 2 ∂y p& 1 = − (12.54) (12.55) Since H is linear in u, and | u | ≤ 1 , we again immediately see The problem, in principle, I now solved. To complete it requires just integration and algebraic manipulation. With φ given by (12.49) and β given by (12.48), we can integrate (12.42) to (12.45). This will bring four further constants of integration; together with a, b and the switchover time t1 we have seven unknown constants. These are determined from the seven end-point conditions at t = 0 and t = T . A typical trajectory is shown in Fig. 12.5. y (12.53) ⎧+1 if u=⎨ ⎩− 1 if p2 < 0 p2 > 0 To ascertain the number of switches, we must solve for p 2 . From (12.54) and (12.55), we see that &p& 2 = − p& 1 + a p& 2 = −ω 2 p 2 + a p& 2 that is, null thrust arc t = t1 &p&2 − a p& 2 + ω 2 p 2 = 0 (12.56) The solution of (12.56) gives us the switching time. maximum thrust arc 0 that the control u is bang-bang, that is, u = ±1 , in fact x Fig. 12.5 Typical rocket trajectory 12.7 Servo Problem The problem here is to minimize Chapter 12 Applications of Optimal Control 59