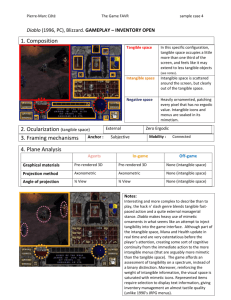

Transfer Pricing and Intangibles

advertisement