Assessment Careers - Institute of Education

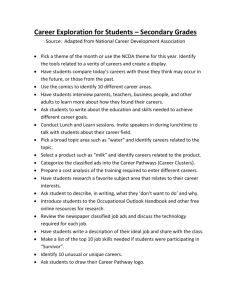

advertisement