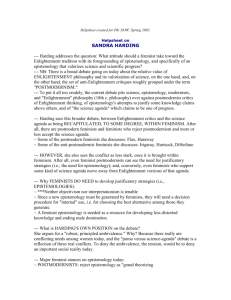

Key Points in Harding

advertisement

Harding: Summary of Key Points

1

Summarizing some key points from Harding and feminist standpoint epistemology:

Rejection of conventional epistemology and its form of objectivity (weak

objectivity)

There is no theoretical unmediated experience

We ought to abandon the search for perfect, mirror-like representations of the

world and the view of science and epistemology as the search for disinterested,

value-free standards

There are no trans-historical grounds for knowledge.

The rejection of ahistorical foundationalism and experiential foundationalism

(269).

We should reject the hard distinction between sociology and epistemology:

standpoint theories have characteristics of both conventional sociologies and

conventional epistemologies.

Knowledge and science in societies stratified by race and gender are largely

produced by homogenous groups which remain unaware of the social and cultural

background assumptions motivating their concerns

Intuitive experience is frequently not a reliable guide to the regularities of nature

and social life and their underlying causal tendencies (163).

Knowledge and science is not value-free: scientific beliefs, practices, institutions,

histories and problematics are constituted in and through contemporary political

and social projects (145)

Human knowledge seeking cannot defy its historical and sociological conditions;

knowledge and science cannot be freed from politics and morals.

Weak objectivity does not direct us to examine the social, historical, and cultural

evidence in support of our “best” or true beliefs: it is too narrow (143)

Knowers are not value-free and our search for knowledge should not be premised

upon the search for ahistorical foundations

Cultural agendas and assumptions remain part of the evidence for scientific

claims

We must identify the cultural values and interests of the researchers (162). The

researcher should gaze back at “his own socially situated research project in all its

cultural particularity and its relationships to other projects of his culture…” (163).

The causal symmetry of good and bad, true and false beliefs: we must provide

symmetrical accounts of both “good” and “bad” belief that incorporate both micro

processes in the laboratory and macro tendencies in the social order

Epistemology and philosophy of science must include as part of its analysis

critical examination of historical values and interests that may be shared within

the scientific community (147); strong objectivity extends the notion of scientific

research to include systematic examination of the powerful background beliefs of

the scientific community (149).

Thinking as “outsiders within”: standpoint theory and strong objectivity requires

that we value the perspective of the Other and investigate the social conditions

that create it. Standpoint theory requires that we incorporate race, class, gender,

etc. There is no “Woman” and are no ahistorical humans. {Note that Part III

Harding: Summary of Key Points

explicitly focuses on such “Others” and that Chapter 11 examines how we might

reinvent ourselves as other.}

Harding must deal with the critique of standpoint epistemology according to which it

maintains a commitment to objectivity and foundationalism. She recognizes that

standpoint epistemology must maintain standards but she sees these standards as distinct

from the kind required by conventional epistemology.

The need to maintain standards: “there have to be standards for distinguishing

between how I want the world to be and how, in empirical fact, it is. Otherwise,

might makes right in knowledge seeking just as it tends to do in morals and

politics” (160). {Is the crux of the problem for Harding? What does she mean by

“empirical fact”?}

Standpoint theorists do argue that women‟s lives provide scientifically preferable

starting points for generating and testing scientific hypotheses compared with the

lives of men in the dominant groups.

Distinguishing between women‟s experience and women‟s standpoint: what

women say and what women experience do provide important clues for research

designs and results, but it is the objective perspective from women‟s lives that

gives legitimacy to feminist knowledge (167).

One can rationally distinguish social conditions giving rise to false beliefs from

those giving rise to less false ones (168).

Ambivalence regarding truth: standpoint theory claims that we can provide good

reasons for dividing beliefs into the false and the probably less false (169); “we

can sort our beliefs into the more versus the less partial and distorted, or into the

more versus the less false, without having to commit ourselves to the belief that

the results of feminist research are „true‟” (185).

2