A. Plan of Investigation To what extent did the child labor laws

advertisement

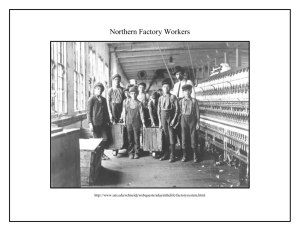

A. Plan of Investigation To what extent did the child labor laws enacted in New York during the late 1880 's and early 1900 's prohibit children from becoming employed at occupations that were potentially harmful to their "[becoming] self-supporting and capable units of society " (Calcott 261)? After the Civil War in 1865, the extent of child labor in New York dramatically increased, leading to a call for legislation in an attempt to regulate the children entering the workforce. The aim of this investigation is to determine how successful these laws were in protecting the children of New York. This investigation will cover the vague provisions and loopholes within the laws that allowed for differing interpretations as well as widespread abuses. This investigation will also cover the lax enforcement of the child labor laws. An analysis of these topics should reveal how successful the New York child labor laws were in protecting child laborers. Most of the research completed will be from secondary sources such as Hostages of Fortune: Child Labor Reform in New York State by Jeremy Felt and Obstacles to the Enforcement of Child Labor Legislation by Florence Kelley. B. 1. Summary of Evidence Child Labor before Legislation During the early twentieth century, the State of New York entered the Gilded. Industry prospered and there was a constant stream of new machinery for the manufacturing industries. The manufacturers often found that this new and innovative machinery could be more easily operated by smaller hands (Lindsay 73). The children provided "a source of cheap labor willing to work long hours" for the many manufacturers who were constantly seeking new ways of cutting costs (Hobbs 106-107). During this time period, "About 300,000 New York children, ages five through fourteen, were out of school" and "some of [the children who did attend school] worked in the street trades or tenements after school until past midnight" (Felt 17). "The state...did nothing to ameliorate their conditions of work, to enforce their attendance at school, or to safeguard their health" (Felt 18). The conditions in which the children were forced to work were often unsanitary and dangerous, leading to the death of many child laborers (Otey 2). 2. Child Labor Legislation During the late 18OO's, proposed legislation attempts for child labor reform failed numerous times (Otey 108). The New York Factory Act of 1886 was implemented as the first real factory law and, therefore, the first attempt at protecting children (Felt 20). A labor law of 1896 stated that "no child should be employed in any factory" (Calcott 27). The Factory Act of 1886 stated that certain ages "were forbidden to work more than sixty hours a week, except for the time spent in making 'necessary repairs.' Any person who 'knowingly' violated the law could be fined" (Felt 20). During the middle of the 1900's, the parents of child laborers were required to produce a parent affidavit, which was supposedly proof of the child's age and ability to work (Calcott 26). In 1928, a bill was passed that required a school official to issue a permit and badge to the children who were old enough to work according to the age limits. The bill stated that the permit and badge would be granted only after "satisfactory proof was shown concerning the child's age; however nowhere in the law does it state what "satisfactory proof constitutes (Calcott 31). In 1903, the Board of Health was required to approve the physical ability of the child for them to work. 3. Enforcement of Child Labor Laws In 1886 only two factory inspectors were assigned to enforce the Factory of 1886. In 1887 there were only eight positions open although "more than four hundred men filed applications" (Felt 21). In a report by the New York Child Labor Committee in 1909, approximately half of the fifty-nine cities in the state were not enforcing the street trade laws. In 1926, thirty-two of the fifty-nine cities in the state did not report any badge issues for the street trades (Calcott 47). In order for a child to work, the Factory Act of 1886 required only the oath of the parent concerning the child's age (Calcott 16). In many of the laws enacted in New York State, a local health officer was required to give work certificates to the children who were seeking jobs (Calcott 20). In 1911, a Brooklyn official dismissed a child labor prosecution by telling the factory inspector that "he should wink at such violations during the holiday season" (Felt 86). In 1901 there were 33,766 recorded child labor law violations by employers and 70 convictions. In 1902 there were 49,538 violations and 7 convictions. In 1903 there were 50,572 violations and 39 convictions (Calcott 245). C. Evaluation of Sources Levine, Marvin. Children for Hire: The Perils of Child Labor in the United States, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2003. One value of this book is the author's use of tables with specific numerical values and cited references from well known and established sources such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics. A second value is Levine's knowledge on the subject of child labor. He is the coauthor often earlier books. This shows that the author has extensively researched the topic of labor. However, this book also contains limitations. The author does not use adequate evidence when supporting a point. For example, Levine states, "A lack of uniformity characterizes the state systems of work permits" (Levine 108). This statement is not supported by any direct evidence or reasons behind its proclamation. A second limitation is the author's lack of cited primary sources. Within the text, there are no firsthand accounts that reveal the attitude of the society. Almost everything that the author presents has been affected by the author's beliefs. Hindman, Hugh. Child Labor: An American History. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2002. One value of this book is the author's use of National Child Labor Committee investigative reports and publications. These reports are primary sources that show firsthand accounts of child labor in different industries. The book also contains many interviews with working children and employers. These firsthand accounts have not been tainted by another author's bias and so the reader is able to interpret them as they choose. The information within this book is also collected from many sources and, therefore, likely presents the most accurate information. A final value for this book is Hindman's use of examples to support his arguments. The examples are precise and relate specifically to that argument. The author rarely states anything that has no relation to the topic at hand. However, Hindman worked as a young boy before the age of sixteen. He has a previous view concerning child labor and the enforcement of those laws. This bias may lead to a slight alteration of the presented data. However, Hindman never worked in a mine, mill, or factory. He instead worked at other small jobs. Hindman never really witnessed the extremes of child labor, and so, this bias did not necessarily originate from the same topic that he is writing on in this book. D. Analysis 1. Child Labor before Legislation The start of the Gilded Age sparked the growth of child labor in New York by creating new job opportunities. Although some historians argue that child labor had been present prior to the late 1800's, it was not as prominent in society (Lindsay 73). Work often took prominence over school. In most lower class families, "a lack of employment by the breadwinner of the family [made] it necessary for the child to make some contribution" (Woodward 103). During the beginning of child labor, there were no laws governing it. This led to working conditions unsuitable for the growth and development of children. Some of the population believed that "manufacturers rendered women and children 'more useful...than they would otherwise be'" (Otey 27). As the evils of child labor came to be known however, it was revealed that child laborers were working in environments dangerous to their health and safety. 2. Child Labor Legislation The enactment of child labor laws was deemed to be nearly impossible because each time a bill was proposed, "the manufacturing interests threatened to leave the state" (Felt 19). The labor law of 1896 stated that "no child should be employed in any factory" (Calcott 27). This was up for differing interpretations depending upon your opinion. The ambiguity of this law allowed parents to bring their children to the factories as helpers. The children were still working in the factories, but "the factory evaded punishment since the child was not employed by it" (Calcott 27). In another instance, the Factory Act of 1886 allowed differing interpretations. Children were not allowed to exceed a set number of hours unless that time was "spent in making 'necessary repairs'" and "Any person who 'knowingly' violated the law could be fined" (Felt 20). This provision allowed the employees to fake ignorance of violations. They were safeguarded against any punishment. Also, the hour limit was ineffective because the law allowed children to work indefinitely as long as that time was spent in making "necessary repairs" (Felt 20). A parent affidavit was required in some instances to prove that a child had the ability to work. Some historians would argue that this affidavit was proof enough of a child's capability; however, the affidavit did not require any actual proof of the child's age. It relied instead on the oath of the parents. In most cases, parents were more than willing to lie to increase their income (Calcott 26). In 1928, a badge was required for children old enough to work. This badge would be issued by a school official; however, the school official did not have to require any proof of age. It was very likely that a "negligent official might accept evidence that was worthless and grant a permit and badge to children under the legal age" (Calcott 31). In 1903, the Board of Health had to approve the physical ability of the child. Some historians believe this was an acceptable means of keeping unhealthy children out of work. However, the laws did not create a standard for the physical examinations and "it thus became a matter more of personal judgment if it was regarded at all" (Calcott 244). 3. Enforcement of Child Labor Laws With the limited number of factory inspectors that were employed, "The Bureau of Factory Inspection.. .found it impossible to visit all the factories" (Felt 21). There were already a scarce number of factory inspectors who would look into child labor. Also, in 1909 and in 1926, children of all ages were working in the street trades without the required badge that stated that they were old enough to work. According to Calcott, "Ever since the passage of the factory law in 1886...there had been much false swearing as to ages" (Calcott 16). This displays that the oath of a guardian was not adequate in ensuring that young children were kept out of workplaces. If they were discovered, their age could not be proven. The employer would have the oath of the parents and the inspector would be forced to accept that as proof. Many laws also required a local health officer to give work certificates. However, "the health boards were.. .neither prepared to take over this additional duty.. .nor could they be expected to develop any real interest in the matter" (Calcott 20). The health officers were disinclined to spend their valuable time on children's work certificates. This failed to lessen the extent of the false oath swearing. Calcott states that "the addition of what amounted to a few extra pairs of eyes for looking at a false oath did not decrease the amount of perjury nor the false certification on the part of the notaries" (Calcott 17). If an underage child was caught working, many judges were unwilling to fine parents who were already poor (Stott 102). Some judges would show blatant disregard for the laws that were in place, a common occurrence among the convictions (Felt 86). The number of violations compared with the number of convictions illustrates to what extent these violations were being pardoned. Employers continued to abuse the child labor laws, finding ways to increase their profits through the use of children without being penalized for those violations (Calcott 245). E. Conclusion The child labor laws that were enacted in New York were not successful in protecting children from entering the workforce at a potentially harmful age. The legislation attempts contained loopholes that allowed for different interpretations, leading to widespread abuse of those laws. The enforcement of the child labor laws was also so lax that employers were rarely convicted for the violations of said laws. F. List of Sources Callcott, Mary Stevenson. Child Labor Legislation in New York: The Historical Development and the Administrative Practices of Child Labor Laws in the State of New York, 1905-1930. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1931. Felt, Jeremy P. Hostages of Fortune: Child Labor Reform in New York State. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1965. Hobbs, Sandy, McKenchnie, Jim, and Lavalette, Michael. Child Labor: A World History Companion. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 1999. Kelley, Florence. Obstacles to the Enforcement of Child Labor Legislation. New York City: National Child Labor Committee, 1907. Lindsay, Samuel McCune. "Child Labor a National Problem." Child Labor: A Menace to Industry. Education and Good Citizenship. Philadelphia: American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1906. McKelway, A.J. "The Child and the Law." The Child Workers of the Nation. National Child Labor Committee. New York: American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1909. Otey, Elizabeth. The Beginnings of Child Labor Legislation in Certain States: A Comparative Study. New York: Arno Press, 1974. Stott, Richard. Workers in the Metropolis: Class. Ethnicity and Youth in Antebellum New York City. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1990. Woodward, S.W. "A Business Man's View of Child Labor." Child Labor: A Menace to Industry. Education, and Good Citizenship. Philadelphia: American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1906.