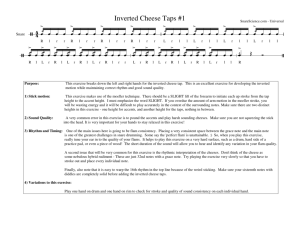

Great Hands for a

advertisement