STUDENT LEARNING WITH CONCEPT

MAPPING OF CARE PLANS IN

COMMUNITY-BASED EDUCATION

SUSAN M. HINCK, PHD,* PATRICIA WEBB, MSN,y SUSAN SIMS-GIDDENS, EDD,z

CAROLINE HELTON, MS,§ KATHRYN L. HOPE, PHD,OROSE UTLEY, PHD,#

DEBORAH SAVINSKE, MSN,y ELIZABETH M. FAHEY, MSN,y AND SUE YARBROUGH, MSN**

Concept mapping, a learning strategy used to understand key concepts and relationships between

concepts, has been suggested as a method to plan and evaluate nursing care. The purpose of this

study was to empirically test the effectiveness of concept mapping for student learning and the

students’ satisfaction with the strategy. A quasi-experimental pre- and posttest design was used to

examine the content of concept maps of care plans constructed by junior-level baccalaureate

students (n = 23) at the beginning and end of a community-based mental health course.

Additionally, students completed a questionnaire to self-evaluate their learning and report their

satisfaction with concept mapping. Findings indicated that concept mapping significantly

improved students’ abilities to see patterns and relationships to plan and evaluate nursing care,

and most students (21/23) expressed satisfaction in using the strategy. This study supported

concept mapping as an additional learning strategy and has extended knowledge in communitybased nursing education. (Index words: Concept mapping; Community-based; Baccalaureate

nursing education) J Prof Nurs 22:23–29, 2006. A 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

N

URSING EDUCATION IS keeping pace with

the changing health-care environment by moving

more student practice experiences from the highly

structured hospital to the home and community.

Community-based nursing necessitates different knowledge and skills to organize nursing care in settings that

are less structured and more diverse (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 1999; Matteson, 2000;

Stanley, Kiehl, Matteson, McCahon, & Schmid, 2002).

Community-based nursing requires a broad perspective of the client (defined as an individual, family,

group, or entire community) and an understanding of

*Associate Professor, Department of Nursing, Missouri State University, Springfield, MO.

yLecturer, Department of Nursing, Missouri State University, Springfield, MO.

zAssistant Professor, Department of Nursing, Missouri State University, Springfield, MO.

§Lecturer and BSN Program Director, Department of Nursing, Missouri

State University, Springfield, MO.

OAssociate Professor and Department of Nursing Head, Department of

Nursing, Missouri State University, Springfield, MO.

#Associate Professor and Nurse Educator Graduate Programs Director,

Department of Nursing, Missouri State University, Springfield, MO.

**Lecturer and FNP Program Director, Department of Nursing,

Missouri State University, Springfield, MO.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Hinck: 1220

West Lakewood Street, Springfield, MO 65810.

E-mail: susanhinck@missouristate.edu

8755-7223/$ - see front matter

the multiple factors that influence the client’s health.

Community-based student learning requires a higher

level of self-direction, critical thinking, and independent decision-making compared to institutional settings

(Kemp, 2003). The focus includes healing the sick, as

in hospital-based care, but also a greater emphasis on

preventing illness, promoting health, and empowering

people to gain greater control over their lives and health

(Kemp, 2003).

Concept Maps

Concept mapping is a means to comprehend multifaceted care. Concept maps (CMs) are diagrams of key

concepts and relationships between those concepts. Concepts are visually presented as words or pictures placed in

a hierarchical structure, with the most important concepts in the center or on top of the page. Secondary

concepts radiate from the central concepts. Lines drawn

between the concepts and propositional statements

written on the lines graphically show the relationships.

Novak and Gowin (1984) recommend six steps in creating a CM: Select a topic, write general concepts, identify

more specific concepts, tie general and specific concepts

together with propositional words that show how the

concepts are linked, make cross-linkages to show

connections, and, finally, reflect and revise the CM.

CMs have gained widespread acceptance in education

as a means for students to learn new information and to

Journal of Professional Nursing, Vol 22, No 1 (January – February), 2006: pp 23–29

A 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

23

doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.12.004

24

HINCK ET AL

understand prior knowledge in new ways. Construction

of CMs provides the opportunity for students to break

new knowledge into small parts (concepts), arrange and

order concepts to make sense, and make connections

between and among concepts (Irvine, 1995; Novak,

1990; Schmid & Telaro, 1990). The process of creating

the CM is necessary for maximum learning to take place.

Students must prepare their own CMs to reflect on

what information is relevant and how it fits together

(Novak, 1990).

Concept mapping results in meaningful learning that

is long-lasting and occurs when the learner consciously

relates new knowledge to prior understandings (Ausubel,

Novak, & Hanesian, 1986). More importantly, concept

mapping is a metacognitive strategy that helps students

learn how to learn (Irvine, 1995; Novak, 1990). Rather

than traditional learning of memorizing facts in specific

contexts, concept mapping helps students recognize

how multiple parts result in a cohesive whole.

Concept mapping has been discussed in nursing

literature as an innovative method of student learning

(All & Havens, 1997; All, Huycke, & Fisher, 2003; Beitz,

1998; Irvine, 1995; Kathol, Geiger, & Hartig, 1998;

Mueller, Johnston, & Bligh, 2001). Most examples of

CMs related to nursing care have presented the identification of and intervention for physiological illnesses

(All & Havens, 1997; Daley, Shaw, Balistrieri, Glasenapp,

& Placentine, 1999; Irvine, 1995; Kathol et al., 1998;

Mueller et al., 2001).

The use of CMs in planning and organizing nursing

students care, in place of traditional care plans, has been

described (All & Havens, 1997; Baugh & Mellott, 1998;

Mueller et al., 2001; Schuster, 2000, 2002). CMs offer a

more effective way to organize and plan care than

traditional care plans that require linear thinking and

are often copied from texts with minimal individualization (Schuster, 2000, 2002). Further, concept mapping

stimulates students to evaluate what information they

still need to gather when in the clinical setting. Nursing

diagnoses are derived from the client’s pertinent conditions and added to the map. Information on the CM

care plan is worded in a similar manner to the traditional

care plan, but the structure is more flexible to show the

relationships between the information. CMs can be used

as visual aids in pre- and postclinical conferences to show

application of nursing knowledge and skills (Baugh &

Mellott, 1998). Evaluation of the CM usually is based on

whether all parts of the nursing process are identified

(Mueller et al., 2001) and how well students apply the

course content to the clinical situation. However, there

are no examples of concept mapping in nursing

literature to show the intricate social, cultural, and

health dynamics considered when planning and evaluating nursing care in community settings.

exams, problem-solving tests, and course grades, as

summarized by Novak (1990). Studies have shown that

using CMs to outline lecture content and texts have

assisted university students to better learn course

content and improve exam scores (Francisco, Nakhleh,

Nurrenbern, & Miller, 2002; Leauby & Brazina, 1998;

Taagepera & Noori, 2000).

Few studies have been conducted to examine concept

mapping as an effective learning strategy for nursing

students (Daley et al., 1999; Rooda, 1994; Wheeler &

Collins, 2003). Nurse researchers have reported that

concept mapping increases the ability of nursing students

to understand massive amounts of content, measured by

multiple choice exams (Rooda, 1994), and promotes

critical thinking, measured by increased complexity in

creating CMs (Daley et al., 1999; Schuster, 2002;

Wheeler & Collins, 2003). Nursing studies have

investigated the effectiveness of CMs that diagramed

physiological aspects of nursing care in highly structured institutional settings only. The use of CMs in

learning to create and evaluate the plan of nursing care

in community settings has not been empirically tested.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of concept mapping as a learning strategy for

junior-level baccalaureate nursing students to plan and

evaluate nursing care during a community-based mental

health course.

Research Questions

1. Is there a difference in the CMs of care plans at the

beginning and end of the course?

2. What are students’ self-evaluations of their learning

and satisfaction with use of concept mapping?

Methods

Design and Sample

A quasi-experimental pre- and posttest design was used

to examine the content and differences of CMs of care

plans constructed by junior-level baccalaureate nursing

students (n = 23) at a Midwest metropolitan university.

Students created the CMs at the beginning and end of a

community-based clinical experience during a 16-week

mental health course in spring 2004. This was the third

clinical course for students, who had prepared traditional care plans in the prior two courses. In addition,

for this study, students completed a questionnaire

reporting their self-assessed learning and level of

satisfaction with use of CMs.

Student and Faculty Training

Measuring the Effectiveness of CMs

The effectiveness of CMs in student learning has been

indirectly measured by higher scores on multiple-choice

Because concept mapping was a new learning strategy

for faculty and students, 11 course and clinical faculty

and 23 students took part in a comprehensive training

CONCEPT MAPPING

program. To help students and faculty develop skills

in concept mapping, the faculty initiated a 2-phase

education plan. First, in the semester prior to student

use, an expert on concept mapping presented a half-day

seminar to nursing faculty about the theoretical underpinnings and purpose of concept mapping in nursing

education. Faculty then devised a plan for student

preparation, course expectations, and evaluation of

concept mapping. Second, to further meet the need for

knowledge and skill development, a nationally recognized expert in concept mapping within communitybased nursing education presented a 1-day workshop

for students and faculty at the beginning of the course.

The workshop provided the opportunity to learn about

and practice creating CMs.

As an in-class activity after the workshop, students

practiced concept mapping to identify nursing diagnoses and supporting subjective and objective data,

nursing interventions, including teaching, client outcomes, and evaluation of nursing care. Case studies of

familiar, common client situations were presented to

determine the student’s baseline knowledge of the

complex components influencing the client’s health.

Students were divided into groups of three or four, and

each group was given a case study of a mental health

client, a large sheet of paper, and colored pencils.

Students worked together to illustrate the relevant

information from the case study. Instructions to

students were to do the following:

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

Identify the client as the central concept in the middle

of the page.

Add the client’s main health concern or reason for

seeking help.

From the main health concern, add two relevant

nursing diagnoses. The concepts can be contained

within circles or other shapes to differentiate them

from each other.

For each nursing diagnosis, list the subjective and

objective data, identified from the case study, that are

associated with the diagnosis.

List current information about medical diagnosis, risk

factors and etiologies, diagnostic tests, treatments, and

medications under the appropriate nursing diagnoses.

List nursing interventions for each diagnosis. Interventions include key areas of assessment, procedures,

teaching, and therapeutic communication.

Add expected outcomes associated with the nursing

interventions for each nursing diagnosis.

Finally, draw lines between concepts to indicate

relationships. Link the concepts and related data by

different types of lines (e.g., arrows, bolded lines,

direct lines, or broken lines), depending on the nature

of the relationship. On each line, use words (such as

related to, contributes to, is necessary for) to explain

the relationship between linked concepts. Illustrations and shapes can be used to clarify concepts.

Develop a map key with codes to explain what each

color and illustration represent.

25

Students Use of CMs During the Course

During the course, students cared for clients from an

assigned community setting such as an adolescent

behavioral health center, substance abuse counseling

center, older adult day care center, and others. Students

each created eight CMs to identify the complex situations

and relationships of mental health clients in the community, prioritize client needs, develop and implement

interventions to meet the needs, and evaluate the

effectiveness of their nursing care.

Because students were not able to have prior contact

with their clients, they began developing the CMs the

day of their clinical experience. Students spent the day

with their clients to learn of clients’ concerns, difficulties, strengths, and adaptive strategies. Students also

reviewed written records to determine information

about the client’s health problems, medical history,

family relationships, and community resources used.

They gathered information on relevant medications,

treatments, and medical diagnoses. Then students

analyzed the assessment data and identified two nursing

diagnoses and interventions related to those diagnoses.

During pre- and postclinical conferences, students

discussed their CMs with faculty and peers. This activity

provided all students the opportunity to think out loud

about the accuracy and completeness of the relationships depicted on their CMs. Students used diagrams,

shapes, and color to code the parts of the nursing

process and included a key to explain their coding.

Students had several days after the clinical experience to

Table 1. CM Grading Criteria

A maximum of 20 points will be given for each CM. The

points will be awarded using the following criteria:

Item

The client’s main health concern is present.

Two clearly stated nursing diagnosis

(NANDA) are present.

Nursing diagnoses are prioritized for

the client.

Subjective and objective data support the

nursing diagnosis.

Short- and long-term goals for each

diagnosis are behaviorally stated with

time frames that are measurable

and realistic (NOC).

Nursing interventions relate to the nursing

diagnosis and are individualized to the

client (NIC).

Evaluation addresses if the short- and

long-term goals were met. Additionally,

indicate if the goal should be continued,

deleted, or replaced with another goal.

Teaching was relevant to the nursing

diagnosis and realistic.

Cross-links are present.

Maximum Points

Possible

1

2

2

2

4

2

4

2

1

26

HINCK ET AL

reflect and evaluate the effectiveness of their nursing

care before the CMs were due.

Students constructed eight CMs, but chose only two

CMs to receive grades. A tool was developed by the

nursing clinical faculty to evaluate the CMs based on the

presence of required elements of the care plan, as well as

whether the plan was appropriate for the client (Table 1).

Human Subjects Concerns

The university’s institutional review board approved the

study prior to data collection. Students were told that

the purpose of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of concept mapping on student learning and that

neither participation nor nonparticipation would affect

their grades. Students signed a consent form granting

permission for their CMs and comments to be evaluated

and included in publications. All students in the course

were required to take part in the class activity of concept

mapping. However, those who did not wish to participate in the study would not have their CMs and

comments included in data analysis. Course instructors

did not know which students agreed or declined to

participate. All students in the course chose to participate in the study. An instructor removed student names

from papers and assigned codes, therefore investigators

did not have knowledge of which students created the

CMs. Additionally, students were asked to not place

names on the self-assessment of learning and satisfaction questionnaires.

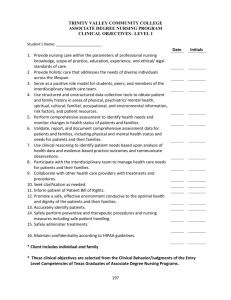

Figure 1.

Measurement and Data Analysis

Scoring CMs

The first (n = 23) and seventh (n = 23) CMs for each

student were scored. These CMs will be referred to as

CM1 and CM7. The CMs scored by investigators may or

may not have been the same as the two CMs chosen by

students to receive grades. The investigators did not have

knowledge of which CMs were graded by instructors.

Investigators scored CMs by assigning points for the

presence of nine items: main health concern, two nursing

diagnosis, prioritization of diagnosis, supporting data,

short- and long-term goals, interventions, teaching,

evaluation of care, and cross-links (see Table 1). The

number of maximum points varied per item from 1 to 4

for 20 total points for the CM. Because the investigator

scoring the CMs did not know the clinical situations,

the investigator did not make judgments about the

appropriateness of the care plan. An example of a CM,

based on student work and minus identifying information, is included in Figure 1.

To establish reliability of findings, two investigators scored all CMs, and the level of agreement was

determined by number of agreements divided by number

of possible agreements. For this process, the two

investigators randomly chose and independently scored

the same three CMs. The investigators discussed identification and scoring of unlabeled items and the minimum

acceptable level of detail for acceptance of items, and

agreement was reached. Then, three additional CMs were

CM of care plan.

CONCEPT MAPPING

27

randomly chosen, independently scored by both investigators, and discussed. Agreement on individual items of

the six CMs ranged from .44 to .70. The remaining

40 CMs were independently scored with an agreement on

items ranging from .41 to 1.0 (mean of .84 for all items).

Lower agreement ratings on the items identification of

goals (CM1 = .53, CM7 = .87) and evaluation of care

(CM1 = .41, CM7 = .83) were a result of continued

differences in recognition of unlabeled items. In addition,

identification of cross-links (CM1 = .59, CM7 = .59) had

lower rater agreement because of differences in interpretation of whether a line was a link or cross-link. Two

investigators scored all CMs; however, only one investigator’s scores were used in data analysis.

Student Satisfaction and Self-Assessment of

Learning Questionnaire

A questionnaire to evaluate students’ satisfaction with

the presentation of CMs and their learning was

administered during class time at the end of the

course. Based on the Student Assessment of Learning

Gains Instrument (Wisconsin Center for Education

Research, 1997), the investigators developed a 21-item

questionnaire consisting of 20 five-point Likert scale

items that determined amount of learning (5 = great

amount, 4 = moderate amount, 3 = fair amount, 2 =

minimal amount, 1 = none). In addition, an open-ended

question asking if there was anything else about

learning with the use of concept mapping they would

like to say. Three doctorate-prepared investigators, who

were not involved in data collection and analysis,

reviewed a draft of the questionnaire for clarity,

appropriateness of the content, format, and style.

Students rated in-class practice (Item 3: M = 3.78, SD =

0.74; Item 4: M = 3.74, SD = 0.81) most favorably and

least favored reading assignments (Item 5: M = 2.65,

SD = 1.34) to learn how to create CMs. Satisfaction with

grading of maps was high (Item 8: M = 3.96, SD = 0.93),

and feedback was appreciated (Item 9: M = 3.96, SD =

0.71). Students said CMs improved thinking ability

(Item 12: M = 3.08, SD = 1.09), preparation for the real

world (Item 13: M = 3.04, SD = 0.83), and ability to

understand complex situations in the community (Item

14: M = 3.17, SD = 0.98). Students believed that CMs

helped them create their care plan for clients in the

community (Items 16–19: M range = 3.22–3.56, SD

range = 0.84–1.09) and enhanced their overall learning

(Item 20: M = 3.26, SD = 1.06).

Four students wrote comments on the questionnaire

(two were in favor of concept mapping and two did not

like the activity). Students’ positive comments about

concept mapping included: bI really liked the concept

map and feel I benefited from doing them. I think they

should be continuedQ and bI liked the concepts. The

feedback we got on them was very useful.Q Two of the

students struggled with CMs as evidenced by these

comments: bIt is difficult to get what I’m thinking into

a concept mapQ and bConcept maps were a hassle and a

burden. I learned from the process of writing things down

but not from putting it into a concept map and connecting

things. I would prefer to go back to care plans.Q

An additional recommendation by students was to

allow adequate time for concept mapping. Many

students said they spent 3 hours or more preparing

the CMs.

Discussion

Data Analysis

Analysis was conducted with SPSS 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago,

IL). A paired samples t test was used to compare CM

mean scores at the beginning and end of the course

(CM1 = CM7). Student self-evaluation of learning and

satisfaction questionnaires were evaluated by calculating the means and standard deviations of each of the

20 Likert items. Students’ qualitative written responses

on the final questionnaire item were analyzed for

common themes.

Results

Students’ CM scores improved (CM1: M = 17, range

8–20; CM7: M = 19, range 16–20), with no students

decreasing scores. Means of the first (CM1: M = 15.35,

SD = 2.95) and the second set (CM7: M = 17.39, SD =

1.12) of CMs were calculated, out of 20 possible points.

A significant increase in comprehensiveness of CMs over

the course was found (t = 3.01, df = 22, P = .006), with

less variation among student scores, as evidenced by the

standard deviation.

Select results of the questionnaire are reported, with

higher scores (1–5 range) indicating greater satisfaction.

This study supported concept mapping as a learning

strategy for nursing students in community settings and

extended knowledge in community-based nursing education. As with all studies with small samples, generalization of findings must be made cautiously. However,

this study adds to the growing body of knowledge that

suggests concept mapping improves students’ abilities to

see patterns and relationships. Prior research suggested

that CMs may help nursing students prepare for clinical

experiences in hospital settings (Daley et al., 1999;

Wheeler & Collins, 2003), settings in which the focus of

care is often on physiological symptoms and medical

treatments, many of which can be gleaned or at least

confirmed with the medical record. Community settings

require different nursing skills because resources may

be more varied and the solutions to problems abstract.

A greater number of factors may affect the response to

teaching and other interventions in the community. An

instructor attested to the practical value of concept

mapping in community settings when she said, bThe

CMs gave a holistic picture of the clients and the

complexity of their life circumstances. It became clear

why many of the clients’ problems were so difficult

to resolve.Q

28

Students had stronger preferences when rating their

satisfaction with how CMs were presented and scored in

class, than when self-assessing how much CMs improved their learning. This may possibly suggest

students are either unsure of how to self-assess learning

or unaware that learning occurred. However, their skills

in creating CM care plans significantly improved during

the course.

Overall, students did not have difficulty identifying the

components of the nursing care plan, probably because

they had prepared traditional care plans for two prior

courses. This was an advantage for students because

they knew the elements of a nursing diagnosis, appropriate interventions, and how to write behavior and time

specific outcome goals. It is notable that the students’

ability to see relationships improved after only one

course using concept mapping although students had

created care plans for two prior courses. Concept mapping expanded students knowledge beyond what they

learned during two courses using traditional care plans.

Investigators have suggested that an increase in

complexity in CMs indicates an increase in conceptual

and critical thinking (Daley et al., 1999; Wheeler &

Collins, 2003) and may be an indirect measure of

clinical performance. Students are more adept at

creating CMs with practice and feedback; however,

further research is warranted to examine how and to the

extent that concept mapping may improve clinical

practice. Additional strategies to directly and indirectly

measure the effectiveness of CMs are needed.

Some students’ dissatisfaction with concept mapping

may be related to the learning style of the students.

Mueller et al. (2001) suggested that concept mapping

may be more difficult for persons who are linear

thinkers, and their CMs will appear as a flowchart

form. In addition, because concept mapping is a graphic

technique, students with visual learning styles may

prefer this method more than do students with strong

auditory or kinetic learning styles. Therefore, concept

mapping is only one of the multiple learning techniques

that can be employed. Further study may explain why

some students prefer the visual diagramming of care

plans, and others prefer the more linear presentation

of information.

Students commented that the CMs took a large

amount of time, often more than 3 hours, to construct.

Others also received feedback that concept mapping was

time-consuming (Daley et al., 1999; Schuster, 2000) and

overwhelming at first (Baugh & Mellott, 1998; Wheeler

& Collins, 2003). Concept mapping may become easier

and faster with practice. This was the first time the

students had created CMs and their abilities may

continue to increase.

Novak (1990) suggested that skill in use of CMs may

develop over 1–2 years. He reported that for 2–4 weeks

after CMs were initiated with university students, a

decline in learning was seen as measured by standard

written exams, and then, test scores increased. Concept

mapping skills may initially develop over one semester,

HINCK ET AL

as found in our study and others (Daley et al., 1999;

Rooda, 1994; Wheeler & Collins, 2003), and then

improve. Longitudinal studies may show whether

improvements in identifying pertinent factors in situations continue or increase in months and years.

Instructors recommended placing the client, rather

than the client’s main health concern, in the center of

the CM to more accurately show relationships. The

main concern, health history, family, environment, and

other concepts flow from the client. Some information

that is important to understanding the client may not

be related to the main health concern. Therefore,

CMs with the client as the focus may show a more

complete picture of assessment. An instructor commented, bAfter reading the CM, I felt like I really knew

this client instead of just knowing a diagnosis about

the client.Q

Whether and how to grade CMs is controversial. CMs

are a visual way students demonstrate learning, making

CMs attractive as a method of measurement. However,

some educators caution against grading CMs because it

can inhibit creativity and learning. Students may

structure their maps to meet the grading criteria and,

thus, not expand their thinking to the greatest extent

possible. To encourage students to try out different

representations, students may be given few instructions

and full freedom in mapping their perceptions of a

client (All & Havens, 1997).

Conversely, if students are given guidelines and

examples, they may have a better understanding of

how to view the client from a holistic nursing

perspective. Many nursing students have a good

understanding of anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology learned in prior coursework and, therefore, may

emphasize these concepts. Because students are novices

in nursing care, they need guidance about what

elements to include in the care plan. Instructor feedback

can then draw attention to any undeveloped areas. It

can be demoralizing to students if instructors give few

instructions and then extensive feedback of what should

have been included.

Methods of grading CMs include assigning points for

the number of concepts, hierarchies, and cross-links

(Daley et al., 1999; Rafferty & Fleschner, 1993), and as

in our study, the elements of the care plan. Evaluating

the quality and appropriateness of a care plan is a

subjective process. Achieving consistency in grading is

difficult, as evidenced by our low interrater agreement

of some items, and may contribute to why some

educators prefer not to grade CMs. Standardizing

scoring with multiple clinical instructors is a challenge.

In this study, the three clinical instructors worked

together closely to achieve consistency. Weekly discussions provided the opportunity to share how they

evaluated CMs. Areas of concern for them included the

level of acceptable detail and wording of CMs. For

example, instructors required that students provide the

detail of specific client behaviors rather than simply

stating that the goals were met.

CONCEPT MAPPING

29

Conclusion

Based on a review of the literature, this study is the first

to examine the effectiveness of CMs to plan and evaluate

nursing care in community settings. The comprehensiveness of students’ care plans improved when they

diagramed the main concepts and relationships between

concepts. Further, most students were satisfied with this

strategy to learn how their clients’ health existed in

context to a situation. Because nursing care in the

community is often complex and changes in each setting,

students are best served if they are helped to learn how to

process new information rather than memorize care

required in a specific setting. With concept mapping, the

focus is on facilitating learning rather than teaching

facts. Concept mapping is an effective learning strategy

to help students apply new knowledge and skills to

clients with complex health-care needs.

Acknowledgments

The research and development activities undertaken in

this project were part of the 2003–2004 Teaching

Fellowship Program hosted by the Academic Development Center at Missouri State University.

References

All, A. C., & Havens, R. L. (1997). Cognitive/concept

mapping: A teaching strategy for nursing. Journal of Advanced

Nursing, 25, 1210 - 1219.

All, A. C., Huycke, L. I., & Fisher, M. J. (2003). Instruction

tools for nursing education: Concept maps. Nursing Education

Perspectives, 24, 311 - 317.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (1999).

Essential clinical resources for nursing’s academic mission.

Washington, DC: Author.

Ausubel, D. P., Novak, J. D., & Hanesian, H. (1986).

Educational psychology: A cognitive view (2nd ed.) New York:

Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Baugh, N. G., & Mellott, K. G. (1988). Clinical concept

mapping as preparation for student nurses’ clinical experiences. Journal of Nursing Education, 37, 253 - 256.

Beitz, J. M. (1998). Concept mapping: Navigating the

learning process. Nurse Educator, 23, 35 - 41.

Daley, B. J., Shaw, C. R., Balistrieri, T., Glasenapp, K., &

Placentine, L. (1999). Concept maps: A strategy to teach

and evaluate critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 38,

42 - 47.

Francisco, J. S., Nakhleh, M. B., Nurrenbern, S. C., &

Miller, M. L. (2002). Assessing student understanding of

general chemistry with concept mapping. Journal of Chemical

Education, 79, 248 - 257.

Irvine, L. M. C. (1995). Can concept mapping be used to

promote meaningful learning in nurse education? Journal of

Advanced Nursing, 21, 1175 - 1179.

Kathol, D. D., Geiger, M. L., & Hartig, J. L. (1998). Clinical

correlation map: A tool for linking theory and practice. Nurse

Educator, 23, 31 - 34.

Kemp, C. E. (2003). Community health nursing education:

Where we are going and how to get there. Community Health

Nursing, 24, 144 - 150.

Leauby, B. A., & Brazina, P. (1998). Concept mapping:

Potential uses in accounting education. Journal of Accounting

Education, 16, 123 - 138.

Matteson, P. S. (2000). What is community-based education? In J. Stanley (Eds.), Implementing communitybased education in the undergraduate nursing curriculum

(pp. 5 - 12). Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges

of Nursing.

Mueller, A., Johnston, M., & Bligh, D. (2001). Mindmapped care plans: A remarkable alternative to traditional

nursing care plans. Nurse Educator, 26, 75 - 80.

Novak, J., & Gowin, D. B. (1984). Learning how to learn.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Novak, J. D. (1990). Concept maps and Vee diagrams: Two

metacognitive tools to facilitate meaningful learning. Instructional Science, 19, 29 - 52.

Rafferty, C. D., & Fleschner, L. K. (1993). Concept

mapping: A viable alternative to objective and essay exams.

Reading, Research, and Instruction, 32, 25 - 34.

Rooda, L. A. (1994). Effects of mind mapping on student

achievement in a nursing research course. Nurse Educator, 19,

25 - 27.

Schmid, R. F., & Telaro, G. (1990). Concept mapping as an

instructional strategy for high school biology. Journal of

Educational Research, 84, 78 - 85.

Schuster, P. M. (2000). Concept mapping: Reducing

clinical care plan paperwork and increasing learning. Nurse

Educator, 25, 76 - 81.

Schuster, P. M. (2002). Concept mapping: A critical-thinking

approach to care planning. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis.

Stanley, J. M., Kiehl, E. M., Matteson, P. S., McCahon, C.

P., & Schmid, E. S. (2002). Moving forward with communitybased nursing education. Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

Taagepera, M., & Noori, S. (2000). Mapping students’

thinking patterns in learning organic chemistry by the use of

knowledge space theory. Journal of Chemical Education, 77,

1224 - 1229.

Wheeler, L. A., & Collins, S. K. R. (2003). The influence

of concept mapping on critical thinking in baccalaureate nursing students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 19,

339 - 346.

Wisconsin Center for Education Research. (1997). Student

Assessment of Learning Gains Instrument. Retrieved December 16, 2003, from http://www.wcer.wisc.edu/salgains/instructor/SALGains.asp.