Contract Law Review

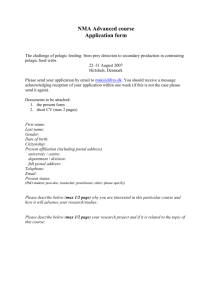

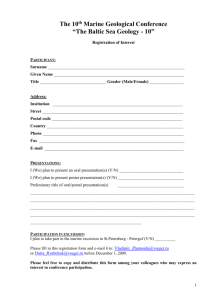

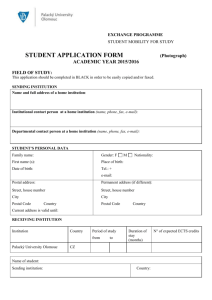

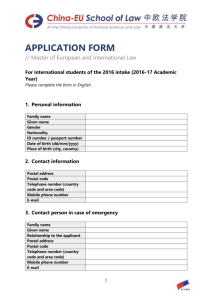

advertisement

The 'Postal Rule' in 21st Century Australia In the 21st century, new technology has changed the way people contract. Particularly, the rise of instantaneous forms of communication and the development of eCommerce has resulted in a significant degree of uncertainty in the law relating to acceptance through these mediums. As acceptance defines the moment a contract is formed, it is critical that it carry clear and unambiguous meaning. In the new age paradigm, courts have attempted to extend and adapt exceptions to the general rule of acceptance rather than reevaluate traditional concepts in light of these new consumer modalities - this has created the ambiguity that agreement should be without. This essay will argue that reform with respect to electronic communications is required to clarify the law in Australia. Further, it will suggest that such reform should not be achieved through superficial distinctions between forms of communication, but rather through an appraisal of acceptance at a first principle level. The 'postal rule' is a common law principle that operates as an exception to the general rule that acceptance must be communicated. v Lindsell 2 1 Early cases such as Adams 3 and Henthron v Fraser justify this exception with an appeal to the practical benefits it produces. Yet, it is hard to reconcile the rule with reference to traditional conceptions of acceptance generally. Communication of acceptance constitutes the general rule as it marks the advent of a 'meeting of the minds' and the point at which parties mutual promises become more than an intention. 4 Pragmatically, the significance of this is that without communication, the offeror may not know they are bound. Against this general rule, the postal rule has been justified by reference to 1 Latec Finance v Knight [1969] 2 NSWR 79. 2 (1818} 1 B & Ald 681 3 [1892] 2 Ch 27. 4 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co [1893] 1 QB 256. implied authorisation, 5 control, 6 business expediency 7 and agency. 8 As Gardener argues though, none of these operate as sufficient justification for the 'postal rule' 9 as within such critiques, arguments can also be made to the counter. Accepting such criticisms, the justification must then come down to an allocation of risk. 10 Thesiger LJ in Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Co v Grant suggests several reasons why he believes the risk should fall on the offeror. 11 However, it is moreover the case that these reasons operate as points of consideration and not justification in themselves. 12 This begs the question; why is there such an exception, if no exceptional reason justifies one? Indeed, it seems somewhat perplexing that such a rule exists for these very reasons, as Australian Courts have, in practice, found them insufficient to justify application of the rule broadly. 13 Although the 'postal rule' has in name lived on, several pertinent cases have narrowed the rule to a point, where acceptance by post may only constitute acceptance if the act was objectively intended to do so. 14 Although the approach in Tallerman & Co Pty Ltd v Nathan's Merchandise (Vic) Pty Ltd was expressly widened in Bressan v Squires, the 'postal rule' in Australia has practically been abandoned. 15 Such a conclusion is justifiable with reference to the restrictions that Bressan imposed on when the 'postal rule' could 5 Household Fire & Carriage Accident Insurance Co v Grant (1879} 4 Ex D 216 (Grant). 6 Dunlop v Higgins (1848) 1 HLC 381 (Dunlop). 7 Ibid; Grant (1879) 4 Ex D 216. 8 Stocken v Collins (1848) 7 M & W 515; Henthron v Fraser [1892] 2 Ch 27 ( Henthron). 9 Simon Gardener, 'Trashing with Trollope: A Deconstruction of the Postal Rules in Contract' (1992) 12(2) Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 170, 173-175. 10 Ibid; see also Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl und Stahlwarenhandelsgescellshaft mbH [1893] 2 AC 34, 42. 11 (1879) 4 Ex D 216. 12 As Above n 9, 174. 13 Tallerman & Co v Nathan's Merchandise (Vic) Pty Ltd (1957) 98 CLR 93, 111-113 (Tallerman). 14 Ibid; Bressan v Squires [1974] 2 NSWLR 460 (Bressan); Nunin Holdings Pty Ltd v Tullamarine Estates Pty Ltd [1994]1 VR 74 (Nunin). 15 Bressan [19 74] 2 NSWLR 460, 463. come into Tallerman. effect; 16 this was, in essence a reiteration of the narrow rule in This analysis is supported by Nunin Holdings Pty Ltd v Tullamarine Estates Pty Ltd, where Hedigan J held that for the 'postal rule' to have effect, it must be reasonably inferred that the offeror contemplated and intended for acceptance to come about through the act of posting. 17 Resultantly, the Australian approach to the 'postal rule' is justifiable solely under an objective analysis. Rather than the 'postal rule' constituting a separate rule, it can moreover be construed as a characterisation of a type of offer, accepted through the performance of an act; namely, the posting of an acceptance. Consequently, it seems appropriate to explore why then the 'postal rule' has been reinvigorated in light of electronic communications. Courts around the world have found it useful to develop the 'postal rule' and its subsequent application to electronic communication by distinguishing 'instantaneous' from 'non-instantaneous' forms of communication. Whilst such a distinction is superficially pleasing, it is arbitrary and spectral insofar as no communication can be said to be completely instantaneous. Further, the categorisation relies on judges approximating methods of communication through a process of reductionism and technical analysis. Despite this, Australian courts have entertained this distinction in a number of cases regardless of the limitations that have otherwise been placed on the ‘postal rule’. 18 the instantaneous/non-instantaneous distinction, Although some academics challenge 19 there is virtually no text that challenges the relevancy of the ‘postal rule’ itself. Ironically, regardless of whether a type of technology is approached under the 'postal rule' in Australia, the outcome will be the same. It is practically irrelevant whether the instantaneous or non-instantaneous categorisation is applied, as the 'postal rule' only gives voice to the objective intent of the parties, which is what the courts would do regardless. Perhaps this is why the courts are yet to authoritatively determine the matter. 16 Ibid. 17 Nunin [1994] 1 VR 74, 83. 18 Olivaylle Pty Ltd v Flottweg AG (No 4) (2009) 255 ALR 632. 19 Eliza Mik, 'Acceptance by Electronic Means' [ 2009] JCL 68. Even so, the subject would be much clearer if current legislation around the issue dealt specifically with this point. State and Territory Electronic Transaction Acts deal with the effects of whether agreement is effective on receipt or dispatch and not whether receipt or dispatch constitutes acceptance. 1999 and 20 Under the United Nations Model Law the Convention on the Use of Electronic Communications in International Contracts 2005, there is also no mention of definitive standards on when a contract is formed. Such domestic and international legislation is misleading as it implies clear standards without providing such. Evidently, there are two prevailing reasons why action should be taken to clarify the 'postal rule' in the 21st century. Firstly, questions of communication characterisation are irrelevant in Australia with within the scope of the 'postal rule' as it stands. Dealing such characterisation creates unnecessary and extraneous ambiguity in the law. Secondly, Electronic Transaction Acts have the illusive appearance of clarifying the law on when acceptance is effective; however, they operate only as technical guidelines to be used once a determination is reached. Ambiguity arises in the effect and scope of such legislation. In order to resolve these issues, comprehensive legislation is required to clarify Australia’s position with regard to the 'postal rule' and its subsequent effect on electronic transactions. When the 'postal rule' is analysed at a first principle level, it is clear that the law is substantively different to how current debate implies it to be. Regardless of whether the 'postal rule' is to be applicable, it has been illustrated that there is a significant degree of ambiguity in when contracts are formed subsequent effects of communication characterisation and such determinations. and the current legislation on Perhaps in line with Australia's common law position, the traditional 'postal rule' should be pushed aside and the objective intent of the parties privileged. Regardless, reform with the goal of clarity should be undertaken. Whilst arguments may be made against reform, such arguments would have to show that there is either not ambiguity in the law, or that ambiguity is tolerable. Clearly ambiguity exists and any eventual reform would without doubt have certainty as a goal. 20 see e.g. Electronic Transactions Act 2000 (NSW), s13(A)(l); Electronic Transactions Act 2001 (QLD) s24(1) New technology is reshaping the way people contract. To facilitate this, the law should be certain and unambiguous. Australia should clarify its position on the 'postal rule' through a process of evaluating the scope of the rule as it stands, and its relevance in the 21st century. Superficial distinctions between forms of communication are irrelevant within the scope of the current law, and should not be the basis of reform. Instead, the 'postal rule' should be evaluated from a first principle level. Such analysis reveals the true character of the 'postal rule' and guides discussion away from superfluous characterisations and Acts, and toward meaningful interpretation and analysis.