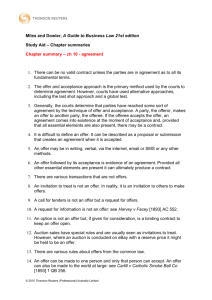

View in PDF - Columbia Science and Technology Law Review

advertisement